Throughout the history of the United States, there have been many landmark court cases. These have paved the way for more equality and an equal shot at the American dream.

Brown v. Board of Education, Hernandez v. Texas, and Obergefell v. Hodges have played a crucial role in shaping the landscape of equality. The outcomes of these cases expanded opportunities for various communities.

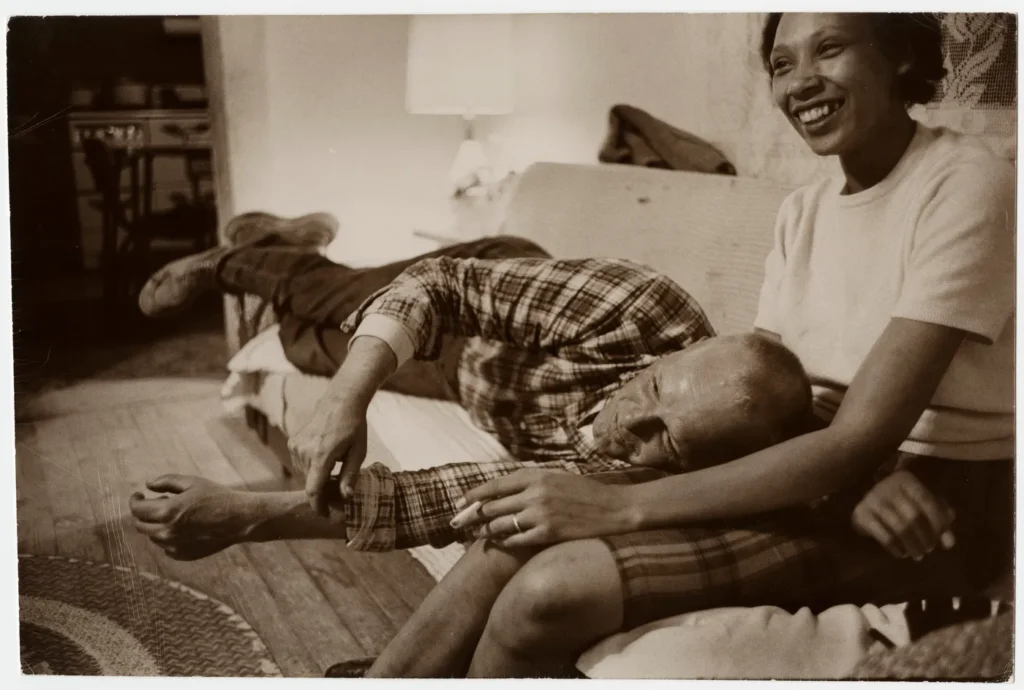

Loving v. Virginia was another stepping stone toward marriage equality. It unfolded in the 1960s and revolved around the marriage of Richard Loving, a white man, to Mildred Jeter, a woman of African American and Native American descent.

They were faced with the choice of legal persecution or being exiled from Virginia. The Lovings chose to seek justice instead.

Their fight took them to the highest court in the land. It resulted in a unanimous Supreme Court decision that forever changed the landscape of American civil rights.

The 1967 ruling not only struck down Virginia’s archaic discrimination laws but also echoed the broader societal shift that was taking place in every city across the country.

Anti-miscegenation Laws In Virginia

Anti-miscegenation laws were statutes that prohibited interracial marriages or relationships between individuals of different races. These laws can be traced way back to the colonial era.

Virginia, in 1691, became the first North American colony to enact legislation explicitly forbidding marriages between people of different races.

The primary goals of anti-miscegenation laws included:

- Preserving Racial Purity: Advocates of these laws sought to prevent interracial marriages and unions in order to maintain the integrity of the white population in Virginia.

- Social Segregation: The laws were also a tool for enforcing social segregation, reinforcing existing racial hierarchies, and attempting to prevent the mixing of races in communities.

- Legalizing Discrimination: By outlawing interracial marriages, these laws institutionalized racial discrimination and perpetuated the unequal treatment of individuals based on their racial backgrounds.

As the United States expanded, so did the implementation of anti-miscegenation laws. By the mid-20th century, a total of 16 states, primarily in the South, enforced statutes banning interracial marriages.

Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws were notorious for their harshness. The Racial Integrity Act of 1924 not only prohibited interracial marriages, but also classified individuals with any traceable African or Indian ancestry as “non-white”.

Enforcement of these laws varied. Many states employed harsh penalties that included fines and imprisonment for those who violated anti-miscegenation laws.

Social pressure and stigma also played a significant role. This made interracial couples subject to public condemnation and ostracism. Even as the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum in the 60s, anti-miscegenation laws persisted in most of the South.

Who Were The Lovings?

Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter met in the small community of Central Point, Virginia. The details of how they met are not well documented, but it is believed that they met through a mutual friend.

Like many areas in the South during the 1950s, Central Point was deeply segregated along racial lines. It was against this backdrop that they met and fell in love.

Knowing their love was forbidden and even illegal, they defiantly forged ahead. They were fueled by the belief that their right to love and build a life together transcended the unjust laws of their time.

As one can imagine, the couple’s decision to get married was met with a mix of emotions within their respective families.

Richard Loving faced concerns from his family about the potential backlash and ostracism they might experience within their community. These were angry times in America.

Opposition to interracial marriages was so strong it could even turn violent. Despite these challenges, some members of Richard’s family were actually supportive of the couple’s happiness.

Mildred Jeter’s family, with both African American and Native American blood, bore the weight of generational discrimination. Her family knew all too well the risks of marrying a white man and the difficulties they might face. Nonetheless, they supported the couple’s decision to be together.

Marriage and Arrest

Both families were well aware of the legal and social hurdles the couple would inevitably encounter, given Virginia’s rigid anti-miscegenation laws. Even though they could be thrown in prison for declaring their love for one another, they still went through with it.

They traveled the short distance into Washington D.C. On June 2, 1958, they exchanged vows in a modest ceremony.

This was not just a union of two people deeply in love. It was a deliberate act of defiance against a legal system that sought to criminalize the very essence of their relationship.

The couple’s hope for a peaceful life was shattered on the morning of July 11, 1958. While they were still in bed asleep, the local sheriff busted down their door and arrested them on the charges of “cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.”

They pleaded guilty. On January 6, 1959, they were sentenced to one year in prison. However, the judge suspended the sentence on the condition that they leave Virginia and not return together for 25 years.

The Lovings moved to Washington, D.C., where they began their new life together. Despite living in an area that accepted their union, they longed to return to their home state of Virginia.

Over the years, Mildred Loving wrote to various officials seeking help. Eventually, she wrote to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy who sympathized with the couple’s plight and referred their case to the American Civil Liberties Union.

Fighting Back

The ACLU took up the case. They assigned the Lovings attorneys Bernard S. Cohen and Philip J. Hirschkop.

Cohen and Hirschkop recognized the constitutional implications of the Lovings’ predicament. They began building a legal strategy that directly challenged the constitutionality of Virginia’s anti-miscegenation statutes.

They filed a motion in Virginia’s Caroline County Circuit Court. They sought to vacate the criminal judgments and set aside the Lovings’ sentences.

The attorneys argued that Virginia’s miscegenation statutes violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This prohibits states from denying any person equal protection of the laws.

After waiting a year with no response, Cohen and Hirschkop took the initiative to escalate the legal battle. On October 28, 1964, they filed a federal class action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Uphill Legal Battle

On January 22, 1965, in response to the federal class action lawsuit filed by the ACLU, Judge Leon M. Bazile issued a ruling in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. Unfortunately, Bazile’s decision reflected the deeply ingrained racial prejudices of the time.

In his ruling, Bazile upheld Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws. He argued that they were rooted in the “long-established and time-honored custom” of racial segregation.

He went further, arguing that the Supreme Court’s decision in the landmark case of Pace v. Alabama (1883), which upheld anti-miscegenation laws, justified the continued enforcement of such statutes.

The ruling was a significant setback for the Lovings. But it only fueled their resolve to press forward. Undeterred, the ACLU immediately appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit.

The appellate court heard the case and, on March 7, 1966, issued its decision. It affirmed Bazile’s ruling and upheld the constitutionality of Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws.

They seemed to have hit another roadblock in their quest for justice. If the state of Virginia was not going to help them then it was time to take the case to the highest court in the land.

The Supreme Court: Loving v. Virginia

On behalf of the Lovings, the ACLU petitioned the Supreme Court to review the case. The court agreed to hear the case, and on June 12, 1967, exactly two years after the appellate court’s decision, the Supreme Court issued its landmark unanimous ruling in Loving v. Virginia.

In a historic decision that would forever change the landscape of America, the Supreme Court declared unanimously that Virginia’s anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional.

Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for the Court, emphasized that marriage is a fundamental right. Denying this right on the basis of race violated both the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The 9-0 ruling had profound implications, not only for the Loving family but for the entire nation. It invalidated not just Virginia’s laws but similar statutes in 16 other states that had bans on interracial marriages.

The Court’s resounding declaration affirmed the fundamental right to marry as a constitutional guarantee. It reinforced the principle that the government had no legitimate right to prohibit individuals from marrying based on race.

Effects of Loving v. Virginia

Although the decision rendered anti-miscegenation laws unenforceable across the country, remnants of these discriminatory statutes persisted on the legal books of several states.

In some states, including Alabama, anti-miscegenation laws remained in effect even after the Loving decision. Astonishingly, state judges in Alabama continued to enforce their anti-miscegenation statute until 1970.

The persistence of these laws prompted federal intervention. It was only through the legal case of United States v. Brittain that the Nixon administration obtained a ruling from a U.S. District Court. This officially put an end to the enforcement of anti-miscegenation laws in Alabama.

However, it wasn’t until the year 2000 that Alabama became the last state to revise its state constitution to align with the Supreme Court’s decision. This change came about through a constitutional amendment which garnered the endorsement of 60% of voters.

The amendment removed all anti-miscegenation language from the state constitution. It finally acknowledged the unconstitutionality of restricting marriage based on race.

References

Racial Integrity Act of 1924

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Racial_Integrity_Act_of_1924

Loving v. Virginia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loving_v._Virginia#

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)