In the 13th century, the Mongols were the undisputed lords of the vast Eurasian steppe, and Ghengis Khan was their fearsome leader.

Under his rule, the various tribes of nomadic herders were finally united. This created a powerful force that went on to decimate towns and cities throughout China, Europe, and the Middle East.

Everywhere they went, the Mongols sowed destruction and ruin. While Ghengis Khan was known to spare those who he found useful, he showed no such mercy for his enemies.

For anyone who crossed the mighty warrior and was captured, you could be sure that punishment would be swift and brutal.

Let’s take a look at the legacy of Genghis Khan and how he dealt with his unfortunate victims.

The Unforgiving Life on the Steppe

Mongols were born and bred to be warriors. From a young age, fathers gave their sons a bow and arrow and taught them to hunt and ride.

Because the Eurasian steppe was so vast, horsemanship was a key skill among the Mongolians. When necessary, they could ride up to 80 miles in a single day to reach an enemy.

Aside from the vastness of the steppe, it was also an inhospitable environment to grow up in. The soil wasn’t suitable for farming so the Mongols developed a nomadic lifestyle and lived off of a diet of milk, meat, and whatever edible plants they could gather. It was out of this challenging environment that the Mongolian culture was shaped.

Genghis’ own childhood is a good example of just how unforgiving life could be out on the Eurasian steppe. His mother was abducted by his father while she was on her way to be married to another man.

Fearing that her betrothed would be killed, she gave herself up so that he could escape. Genghis’ father then took her back to his lands to join his other wife and her two children.

When he was nine years old, Genghis’ father took him to another camp to become betrothed to a young girl his same age. This was a typical tradition among Mongol children.

Genghis Learns to Fend For Himself and Fight to Survive

After leaving Genghis with the girl’s family, his father was killed on his way back to his family. It seems that all of his raidings had caught up with him and while sharing a bowl of milk with some Tartars, one of them slipped him some poison. He died a few days later.

With the death of Genghis’ father, the boy immediately returned to his camp – only to find it in a state of abandonment. It seems that the rest of the tribe, which included Genghis’ uncles, saw no value in the women and young children that his father left behind.

Instead of caring for their kin, they refused to take them along with them. With resources hard to come by in the hostile environment of the steppe, this was a death sentence. From that moment on, the two mothers and their children had to fend for themselves.

Genghis Khan struggled over the next few decades – first learning to survive, and then becoming a leader. He endured captivity as a child and fought a years-long war against his blood brother. He eventually fought and defeated his foster father who, in his old age, became paranoid and turned on Genghis Khan.

Finally, at the age of 44, Genghis Khan could declare himself ruler of the entire Mongol nation, which included up to one million inhabitants spread out along the steppe. As a leader, his next task was to provide for his people. Like any good Mongol, he did so through warfare.

Genghis Khan’s Chinese Campaign

To the east of Genghis Khan’s vast territory lay the Jin Empire. It was situated between the lands of the Mongols and Southern Song China. This meant that it impeded trade that could have been very profitable for the Mongols.

Moreover, the emperor of the Jin regarded Genghis Khan as little more than an annoyance and didn’t hesitate to show his disdain for him. For that, the emperor and his people would soon pay a heavy price.

In 1211, the Mongols crossed over the Great Wall of China and entered the land of the Jin. On their way, they terrorized the local population, slaughtering peasants and burning villages.

Sometimes, the Mongols used the captive peasants as human shields or as bridges that they walked across to reach the fortified walls of towns. By the time they reached Beijing, the Mongols left millions of the emperor’s people homeless or dead.

But the worst fate was saved for the inhabitants of the Jin capital of Beijing. After laying siege to the city for three months, Genghis Khan and his men finally broke through the defenses.

The Mongols poured through the streets, raping, killing, and looting. Young women threw themselves from the battlements to avoid being violated by the invading Mongol warriors.

In the emperor’s palace, the Mongols set about slaughtering everyone and taking all of the precious items they could find. The destruction that the Mongols left behind them in Beijing stretched for miles, with corpses heaped together in massive piles and rotting in the sun.

The Mongols’ devastation of Beijing was breathtaking. But it was also pretty typical of how the Mongols treated their enemies. Beijing was just the beginning.

Genghis Khan Takes Revenge on the Shah

Even worse devastation lay in store for Shah Ala Ad-din Muhammad II, who ruled an empire that stretched from India to modern-day Turkey. The Shah, with his mighty army, wealthy cities, and lavish palace, probably thought he had nothing to fear from Genghis Khan and the nomadic Mongols.

But within just a few years, he would be forced to flee his crumbling Khwarazm empire on horseback. He learned all too well the terrifying fate that awaited him if Genghis Khan ever caught up to him.

The Shah’s downfall began with what he must have thought was an arrogant message from a distant barbarian. The three Mongol envoys who visited the Shah had been sent by Genghis Khan himself.

They carried a letter describing the Mongol leader’s wish to establish trade relations. The letter, which was signed, “The seal of the emperor of Mankind” did not impress the Shah. But he was interested in what the Mongols could offer him. He signed the treaty.

The Mongols Arrive in the City

The first Mongol caravan arrived in the city of Otrar and included gold, silver, and 500 camels loaded with sable furs from the Eurasian steppe. It was an impressive display of wealth and power that the city’s governor, Inalchuq, had a hard time accepting.

He wrote a letter to the Shah claiming that the Mongols bearing the precious items had to be spies. The Shah responded by telling the governor that if he could demonstrate that he was right, then he had his blessing to kill all of the Mongols.

Inalchuq, however, simply skipped the part about proving his claims. He executed the ambassador, all of the merchants, and even the camel driver. One slave escaped and brought word of the slaughter back to Genghis Khan himself.

Surprisingly calm, Genghis Khan did not retaliate right away. Instead, he sent an ambassador to the Shah along with some guards to demand that he punish the errant governor. Instead of complying with the request, the Shah beheaded the ambassador and burned the beards off of the others’ faces, a painful act that was meant to humiliate the Mongols.

It was at that point that Genghis decided to punish the Shah.

Genghis Moves His Army and the Siege Begins

Genghis’ army of 200,000 mounted warriors did not scare Shah Muhammad II.

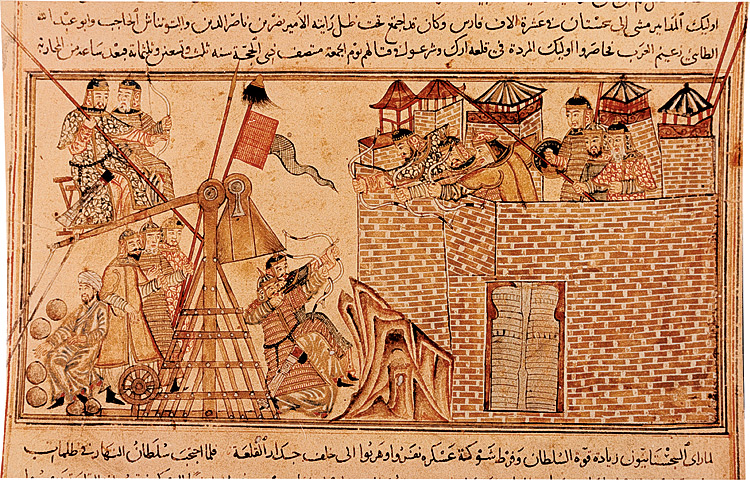

His army was twice that size and he didn’t think the barbarian nomads would have any way to break through his heavily fortified cities. But Genghis Khan learned a lot from his campaigns in China.

He brought with him siege equipment taken from earlier battles as well as Chinese engineers. It took him five months of constant siege warfare, but finally, Genghis Khan and his army breached the walls of Otrar.

Once inside, the Mongols made no distinction between useful citizens and those that could be disposed of. Nearly everyone was slaughtered regardless of their age or sex.

From deep inside the city’s citadel, the governor barricaded himself with the other survivors for as long as they could, while the Mongols went around the city raping the women and enslaving the men.

One can only imagine what the cowering governor now thought about the Mongol foe that he had once brazenly insulted.

After two months, the citadel fell.

While warriors rushed in and killed everyone in sight, the governor climbed onto the roof. Genghis gave special orders to his men to keep the governor alive. He had a special punishment in store for him.

Instead of killing him, the Mongols captured the fleeing man and took him north to Genghis’ camp. There they executed him in a way that they thought fitting for a man so enamored of wealth. They poured molten silver into his eyes and ears until he finally died.

Otrar was not the only city to feel Genghis Khan’s wrath. In the city of Nishapur, what should have been a relatively peaceful occupation turned into a bloodbath.

Genghis Set His Sights on Nishapur

Genghis Khan was a brutal warrior, but he had certain rules that included respecting towns that surrendered. When Nishapur surrendered, Genghis appointed administrators to rule the city, but he left the citizens unharmed.

Then the people of Nishapur tried to retake their city, which turned out to be a mistake. They killed an administrator and reclaimed control of the city, but only briefly. Genghis Khan soon returned and retook Nishapur.

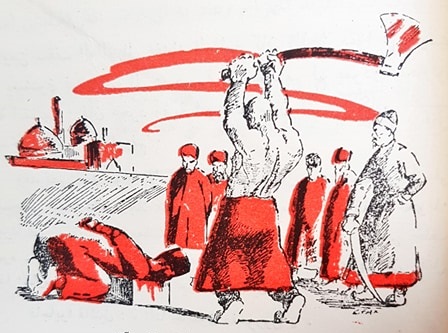

Unfortunately for the Nishapur citizens, Genghis Khan’s son-in-law was killed during the fighting. To seek justice, Genghis Khan asked his grieving daughter what should be done with the treacherous city.

She replied that all of the men, women, and children should be killed, decapitated, and their heads sorted into three separate piles. Genghis Khan did as she requested.

From a young fatherless boy surviving on the Eurasian steppe to the ruler of the mightiest nation on the planet, Genghis Khan did not rise to power by being soft. He maintained a sense of honor and loyalty, but his strict code also included punishing his enemies in horrific ways.

As Mongol armies continued to plunder Europe, Asia, and the Middle East in subsequent centuries, new Khans would come and go. And each one would build on Genghis Khan’s legacy of expansion, conquest, and extreme brutality.