Last updated on January 27th, 2023 at 07:34 pm

During the medieval period through the Tudor era, executions were common in England. Kings like Henry VIII executed thousands of his subjects, including two wives.

Queens like Mary I (who earned the nickname Bloody Mary) burned protestant heretics at the stake. Even royalty wasn’t safe from a swift and brutal death. For example, Charles I was executed during the English Civil War in 1649.

Historians spend a lot of time talking about the people at the top who dole out executions, but they’re not the ones who are getting their hands dirty. Behind every tyrant, some people take on the role of executioner.

One of the most famous of these executioners was Jack Ketch.

The Early Life of Jack Ketch

Surprisingly, Jack Ketch is one of the few whose name is still known today, becoming synonymous with death and the devil in England due to his bloody work during the later 17th century.

We don’t know much about his early life, but we know that many executioners in England during this period were once criminals themselves, and Ketch was no exception. He served time at Marshalsea Prison in Southwark.

Ketch apprenticed under Edward Dunn and succeeded him as an executioner in 1663. Dunn himself apprenticed under Richard Brandon, who famously executed Charles I.

It’s not until the 1670s and early 80s that we start to see regular mentions of Ketch.

The first recorded mentions of Ketch was in court dating to January 14th, 1676, and a 1678 broadside where he is depicted executing the catholic martyr, Edward Colman.

A 1681 document also describes how Ketch hung a man named Stephen College for half an hour before quartering him and throwing his entrails in a fire.

In 1682, Ketch went on strike and was able to negotiate a better wage. On top of his executioner’s pay, Ketch could sell the clothes of the dead or the rope that hanged him and likely receive bribes from his victims in exchange for a speedier or cleaner execution.

At this point, Ketch was a simple servant of the crown, carrying out executions where needed. But, in the next few years, he would carry out two botched executions that would make his name live in infamy.

Executing Lord William Russell

In 1683, the botched execution of Lord William Russell would help ensure his name would go down in infamy.

Lord William Russell was one of the leading members of the Country Party, who would someday become the Whigs. Russell was openly opposed to the accession of King Charles II’s brother James, who was openly Catholic.

As a result, he was sentenced to death for treason, with Jack Ketch serving as the executioner.

It took Jack Ketch an unsightly four blows to remove his head. Unfortunately, the typically bloodthirsty crowd reacted so poorly that he was forced to write a formal apology, claiming he was interrupted while swinging, which is why he wasn’t as efficient as usual.

The Botched Execution of James Scott, Duke of Monmouth

Jack Ketch’s reputation would take a further turn for the worse during the execution of James Scott, Duke of Monmouth.

The Duke of Monmouth was one of Charles II’s illegitimate sons responsible for the failed Monmouth Rebellion in 1685 when he attempted to capitalize on his Protestant faith to usurp his Catholic uncle. As a result, he was sentenced to die on July 15th, 1685.

Knowing that it took four swings to behead Lord Russell, Monmouth paid Ketch 6 guineas and promised more after he was dead if the execution was swift.

It isn’t known if this bribe insulted Ketch or, as some speculate, others paid him more for the execution to go poorly. Possibly, it was neither, and Ketch was just incompetent. Either way, the execution did not go well for the Duke of Monmouth.

After paying the bribe, the Duke of Monmouth touched the ax blade and told Ketch that it wouldn’t be sharp enough to cut his head off in one blow. Ketch assured him that the blade was fine and attempted to carry out the execution.

The first blow inflicted a small wound, resulting in the duke pulling his head off the block to give Ketch an angry look. He swung three more times, but that only led to the duke’s body convulsing with the head still partially attached to his head. It took a few more swings to kill him and a butcher knife to cut the neck sinews and remove his head.

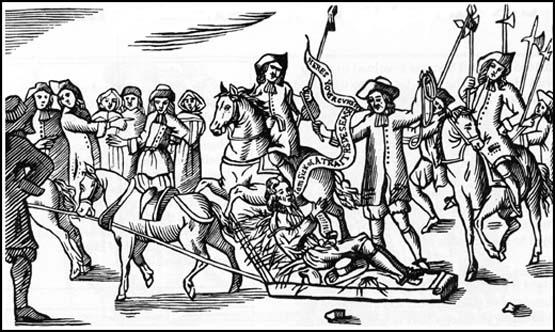

If the crowd was angry enough to force an apology for Russell’s execution, you could imagine how angry they were now. A riot broke out, and Jack Ketch had to be escorted away by armed guards, or he would have likely been torn to pieces.

The Later Life and Legacy of Jack Ketch

It wasn’t much longer before Jack Ketch was relieved of his duties. This wasn’t because of the botched executions but a confrontation with a sheriff that lost his job.

In January 1686, he was sent to Bradwell prison while his assistant Paskah Rose took his place. Ironically, Rose would be hung months later at Tyburn for robbery after Ketch was released from prison a few months later.

In November 1686, a little over a year after his horrific botched execution of the Duke of Monmouth, Jack Ketch died.

Jack Ketch’s reputation would keep him alive in the minds of many for the next three hundred years. The most famous was its use as slang for any executioner, but it became more common than that.

People facing execution became “Jack Ketch’s Pippin,” nooses were “Jack Ketch’s Necklace,” and Newgate prison even named the room where they boiled the limbs of those quartered “Jack Ketch’s Kitchen.”

I would query the notion that Henry VIII executed “thousands” of his subjects, though it’s easy to imagine that was the case when examining the fate of his wives and other nobles. Execution was, head for head, more prevalent the closer to power the victim walked – thus a higher percentage of the nobility and those who challenged the church faced the block, than the peasant class. If you kept your mouth shut, got on with your communal farming, paid your tithes and lived a quiet life, it was far more likely you’d die of disease than execution. The nobility lived a high-stakes power-game.

-exhalse slowly-

Jesus, Britain, you need help.