Last updated on January 27th, 2023 at 05:07 am

We define different societies by the diverse ways they structure economic life and arrange daily life around those same economic activities. For example, in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, life depended on agriculture along the River Nile in Egypt and the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers in Mesopotamia.

Accordingly, they established their villages, farms, and cities throughout the riverine routeways, which dominated these geographic regions.

In the twentieth century, economic life was played out in city centers where the land became so expensive that people fled to find more affordable and pleasant housing in the suburbs. And in medieval Europe, life was organized according to the manor of the feudal lords. But what was manorialism, and how was life in the medieval manor arranged?

The Feudal Lord

The feudal lord was the center of the Medieval manor. These were figures like an earl or baron or a highly successful knight in some cases. Each had been granted a large estate or manorial lands by the king or queen, their liege lord.

The idea of feudalism was that the monarch theoretically owned all of the lands in their dominion. However, because they could not possibly administer all of it themselves, they granted large portions to these feudal lords, who then paid feudal dues to the crown for those same lands.

The feudal lord then went and lived on the land, drawing peasant families to live there as well, who conducted the actual work on the manor, such as tilling the land, raising livestock, milling flour and corn, and engaging in construction work. Thus, the medieval manor was a self-contained economic unit.

How was the Layout of a Medieval Manor?

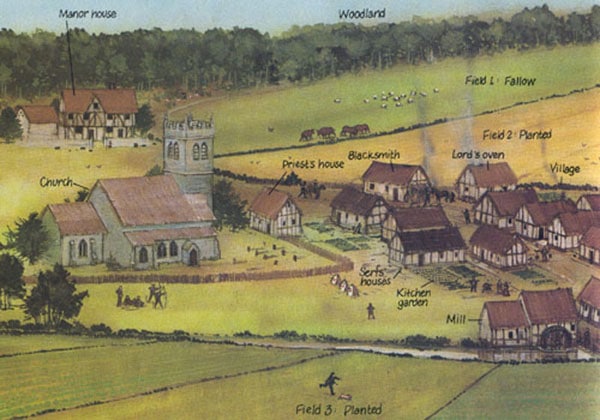

Most medieval manors would have followed a specific layout. At the center of them was the lord’s manor house or castle, a highly elaborate defensive castle sometimes surrounded by a wall and moat in certain places and times but a more modest dwelling home in other regions.

The wider manor consisted of hundreds and, more likely, thousands of acres of land. In relative proximity to the manor house was usually a peasant village comprised of between 10 and 20 modest cottages.

Others might have lived dispersed on the manor lands. Finally, some further buildings were throughout the manor, notably a parish church.

However, the lord, his family, and retainers might have had access to a separate chapel attached to the castle, and a mill, which often would have been sited on the banks of a river to provide a source of natural energy to drive it.

Agriculture at the Medieval Manor

Agriculture was the primary economic activity of the manor. But what might surprise a modern-day time-traveler who headed back to thirteenth-century France, or England was that the land was primarily comprised of enormous open fields.

There were very few ditches, primarily geographical phenomena introduced across Europe between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries as feudal lords began parceling up their lands into small economic units and selling them to a rising middle class.

During the Middle Ages, these open fields on the manor were accessible to the peasantry.

Despite the lack of ditches to demarcate different sections, every peasant and his family would have been aware of what strip of the open fields they were allowed to use to produce their food.

The lord retained a significant proportion of this agricultural land as his demesne lands for his own use.

In return for their use of the open fields, the lord expected the peasants to pay them or the church. For instance, the church received a tithe or one-tenth of the overall harvest and the first fruits, a portion of the first bounty of the harvest.

The Lord expected the peasants to provide a certain amount of days of free labor each year to the lord, during which they would farm his demesne lands or carry out work of another kind.

Other Labor at the Manor

Some peasants would be asked to chop wood in the forest lands on every manor.

The peasants also had access to these woods and could take away a certain amount of wood for construction work or to use as firewood in their cottages. At all times, the manor was a sustainable, circular economy.

The forests were never over-exploited, as to do so would strip the manor of any firewood for years to come. Similarly, sections of the open fields were left fallow periodically to allow them to replenish their nutrients in an age before industrial fertilizers.

The manor was self-reliant in other ways. Peasant women often produced the clothes most of the estate’s residents wore.

There would typically be a blacksmith, turner, and carpenter resident in each manor to produce construction materials, plows, tools, and other goods necessary to sustain economic life.

In contrast, a miller and baker produced the staple food of the manor: bread. Life was seasonal, with the drudgery of agricultural work punctuated regularly with religious festivals such as saints’ days, Easter, and Christmas.

The Manor After Feudalism

The medieval manor later evolved as feudalism ended to become the early modern aristocratic estate. This retained many of the same features of the medieval manor but began to adopt a capitalist system as the peasants no longer had access to standard fields on the manor lands.

Instead, these came under the exclusive ownership of the lord, who either enclosed the commons with ditches or sold portions of it off to a growing bourgeois middle class.

Alternatively, he retained the lands and hired wage laborers to work them for him. Thus, the long process whereby peasants became wage laborers began in the sixteenth century as the medieval manor declined and disappeared.

Sources

J. Z. Titow, ‘Medieval England and the Open-Field System’, in Past & Present, No. 32 (December, 1965), pp. 86–102.

Jules N. Pretty, ‘Sustainable Agriculture in the Middle Ages: The English Manor’, in The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 38, No. 1 (1990), pp. 1–19; Ben Dodds, ‘Demesne and Tithe: Peasant Agriculture in the Late Middle Ages’, in The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 56, No. 2 (2008), pp. 123–141.

Douglass C. North and Robert Paul Thomas, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Manorial System: A Theoretical Model’, in The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 31, No. 4 (December, 1971), pp. 777–803.