Last updated on January 27th, 2023 at 05:04 am

In the summer of 1858, the people of London were in for a nasty surprise. The stench of rotting garbage and human waste was so putrid that it made Parliament members vomit and faint.

This smell, known as the Great Stink, lasted for weeks and drove many residents from their homes. So what caused this terrible smell? Let’s explore what caused the Great Stink of London and how the city finally resolved it.

How The Population Of London Doubled

In 1800, the population of London was just over one million people. But by 1850, the population had more than doubled to over two and a half million.

This massive population growth put a strain on the city’s infrastructure, reinforcing the irresponsible behaviors of the capital’s politicians and authority figures.

The streets were still crammed with hastily built houses without flushable toilets. While London had a sewer system, it was extremely outdated.

Even if a home possessed a working sewage system, the waste was only funneled into the old sewers and eventually into the Thames. As a result, there were only a few thousand privies (outdoor toilets) for the entire city!

Instead, people threw their waste into the streets, where it would mix with rotting food and other garbage. “Night Soil Men” would come along and collect some solid waste for fertilizers, but much of it still made its way into the river.

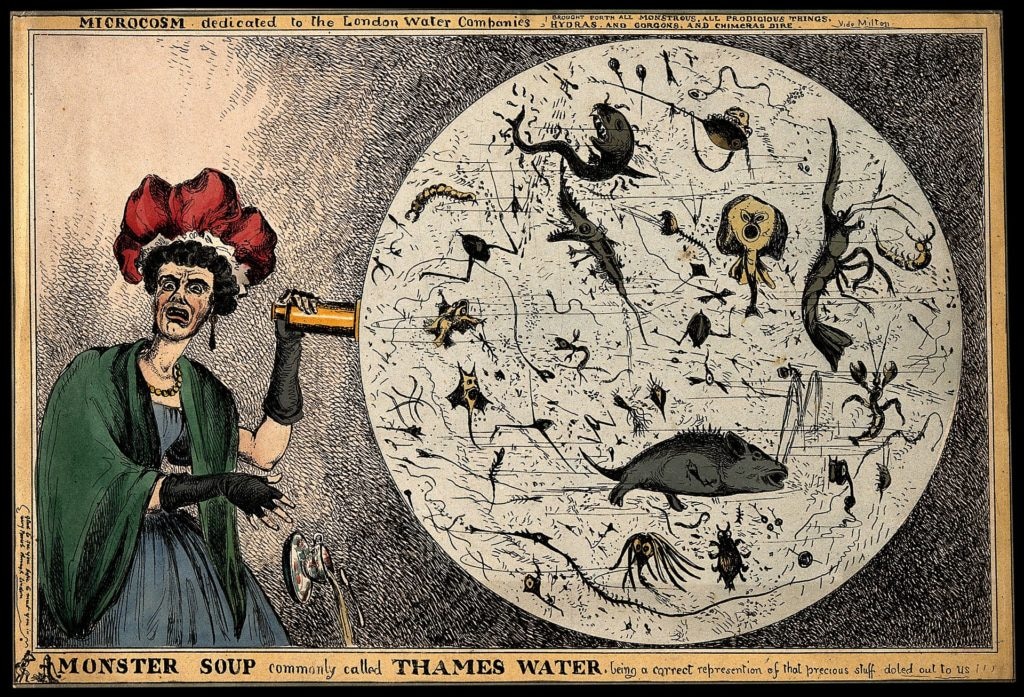

This human activity produced too much trash for city officials to handle. So, despite the reality of London’s situation, its inhabitants continued to use the Thames as a water source and a dumping ground.

An Insidious Odor Begins To Fill The Air

In the early 1800s, some people started to speak out about the terrible conditions in London. They argued that something needed to be done about the city’s many problems. But it wasn’t until 1858 that Parliament did anything about it. Why? Unfortunately, most Londoners were used to the smell despite the horrid conditions.

For centuries, the Thames had been used as a dumping ground for the city’s waste. Perhaps the situation wouldn’t have gotten so out of hand if London’s population hadn’t exploded in the 1800s.

Water bodies can naturally cleanse themselves to a certain extent. But when you add too much waste, it becomes overloaded, and the natural ecosystem can no longer function properly.

The wealthy few who could afford toilets were the only ones to benefit from them. Unfortunately, London’s sewer systems were only designed to handle water, not waste.

Everyone assumed that introducing toilets would improve the situation, but it worsened. The stench of the Thames became so bad that it started to infiltrate and pollute the air.

Cholera, A Waterborne Illness

In the early 1800s, before the Great Stink, there were several outbreaks of Cholera in London. Cholera is a disease that comes from contaminated water.

The city’s unsanitary conditions caused these outbreaks. Because the sewers couldn’t handle the massive amounts of waste, effluent flowed into the river constantly. Historical sources mention that three Cholera outbreaks occurred from 1831 to 1854, taking thousands of lives each time it struck.

This development should not have surprised anyone as the poorer inhabitant got their everyday water from the river, then bathed in and drank the contaminated water.

Believing they could get sick simply from the odor, inhabitants panicked, but a physician named John Snow reassured them that it wasn’t the case. Instead, he speculated that Cholera was a water-borne illness, and they needed to focus on cleaning the river. Unfortunately, no one heeded his warning.

It was until Michael Faraday, an English chemist and physicist, publicized his support of reforming the Thames that people began to listen. He observed the river’s condition and reported that the once majestic body of water had transformed into a pale brown fluid with a horrible smell and clouds of fecal matter.

A Perfect Storm Of Conditions

Citizens were calling for the government to clean up the Thames, but their pleas were unheard. However, in 1846, Parliament enacted the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act.

The idea was to close the old cesspits; some of these structures were used during the time of Henry VIII. Unfortunately, while the idea was to improve the situation, Parliament only worsened the city’s problems.

By the mid-1850s, London’s Parliament realized they had a massive, persistent problem. The soaring population led to more factories regularly putting dirty air pollutants and dumping just about anything into the Thames.

“Dirty Father Thames,” 1848

For instance, even waste from slaughterhouses made its way into the river. Yet, Parliament tried to ignore the issue, refusing to leave their newly built Palace of Westminster.

But that all changed in 1858 when a sweltering and dry summer caused the stench to become unbearable. The heatwave caused the waste to ferment, and despite their attempts to mask the smell, it permeated everything. Worried about the effect on the population, Parliament enacted a bill in eighteen days to address the remediation of the Thames.

The Chief Engineer of The Metropolitan Board Of Works

Parliament tasked Joseph Bazalgette, the Chief Engineer of The Metropolitan Board Of Works, to clean up the river. He proposed an ambitious goal: build a series of sewers to intercept the waste before reaching the Thames.

Bazalgette’s project required the construction of 82 miles of main sewers, 1000 miles of street sewers, and 85 miles of an embankment.

Bazalgette replaced approximately 150 miles of old sewers during this time. In total, the project cost the government a sum that would be $300 million today. In addition to the barrier, Bazalgette built pumping stations to move the sewage away from the city. This project was one of the most significant engineering feats of its time.

However, the project wasn’t popular with everyone as it required the displacement of many residents, the demolition of houses, and the loss of businesses. Nevertheless, Bazalguette completed the project in 1870.

The Embankment Was Largely A Success

The project prevented waste from polluting the Thames, improved the city’s drainage system and modernized its sewer system. Eventually, the odor dissipated, and London’s drinking water was cleaner.

One more Cholera epidemic struck in 1866, but the new sewer didn’t connect the East End of London to Bazalgette’s system by then. As a result, the Thames became the Great Stink of London and was a turning point in the city’s history. It led to London’s modernization and improved its citizens’ quality of life.