The legendary figure of Merlin has been a part of the Western imagination for centuries. From tales of King Arthur to more modern interpretations, Merlin has been a source of mystery and enchantment.

But who was the real Merlin, and where did the stories of this powerful wizard come from? The answer may surprise you.

Grab a bucket of popcorn and buckle up as we explore the historical development of the legendary wizard, from his obscure origins to what we know him today.

Here we go!

Merlin — The History of The Kings Of Britain

In pop and modern-day storytelling culture, the popular opinion is that Merlin was a fictional character developed in and for the Arthurian legend. This, however, is a tad bit farther from the truth. While the myths of Camelot frequently orbits around the legendary wizard, that is not where he originated.

The Welsh clergyman Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain contains Merlin’s first literary appearance (c. 1100 – c. 1155 CE).

The original name Merlin isn’t an individual’s name per se. Its etymology proscribes as a toponym (a place name), specifically the Welsh Caermyrddin (“Merlin’s Town”), which alludes to the town of Carmarthen, where Merlin was born.

The original character Merlin was an amalgamation of numerous mythological and historical personalities. To develop Merlin Ambrosius — the first comprehensive mention in history, Geoffrey merged the tales of the Romano-British warmonger leader Ambrosius Aurelianus and the North Brythonic lunatic prophet Myrddin Wyllt.

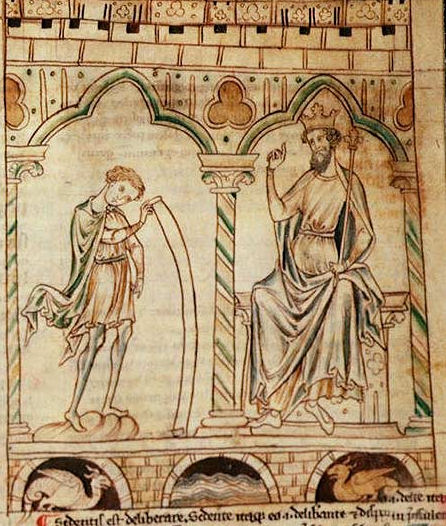

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of Merlin and Ambrosius in the History of the Kings of Britain (1136) starts with the story of Vortigern, who, upon becoming king of Britain, attempts to build a fortress in Snowdonia. He discovered that the foundation of the fortress kept sinking into the ground. No matter what he did or ordered his men to do, it was impossible to keep it standing.

With no solution in sight, Vortigern turns to his magicians for answers. They told him what he must do. He had to find a boy with no father and sprinkle the fortress’ foundation with his blood.

At this moment, Merlin arrives. Merlin, in this arc, was a precocious child, a young boy born of a mortal woman and an incubus, a lesser demon. On appearing before the king, Merlin convinced him that the magicians were wrong. He proved his wizardry prowess by making a series of short prophesies on the spot, all of which were accurate.

Merlin, with ease, thanks to his new credibility, explained to Vortigern that the tower’s foundation was inept because beneath it were two dragons embroiled in combat. The two dragons were pseudonyms representing the Saxons and the Britons.

In an earlier version of this tale — particularly Nennius’ Historia Brittonum- Ambrosius, half of Geoffrey’s Merlin character, was the young boy summoned for sacrifice. In this version, Ambrosius convinced Vortigern that he should be in command if Vortigern wanted the tower— pseudonym for the kingdom — to stand.

Geoffrey’s version of the story excluded Ambrosius(Merlin) from taking the throne insidiously. He altered the narrative by adding two additional tales and a lengthy portion featuring Merlin’s prophecies, resulting in Merlin’s first incorporation into Arthurian legend.

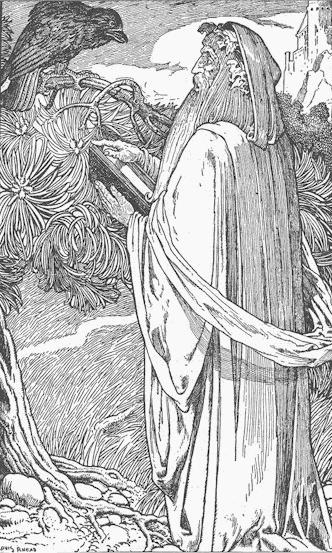

He modified the original narrative by adding two other stories — the legend of Merlin constructing Stonehenge as Ambrosius’ final resting place and that of Uther Pendragon slipping into Tintagel to have Arthur with Igraine, his adversary’s wife — and a lengthy addendum featuring Merlin’s prophecies. This was the origination of Merlin’s incorporation into the Arthurian legend.

Geoffrey’s coverage of Merlin’s mythology only went so far. The tales of Merlin serving as Arthur’s tutor, for which he is most known today, are not included in this variation. Merlin gained popularity immediately, especially in Wales, shortly after his debut in folklore. Following several adaptations from here, he eventually assumed the role of Arthur’s instructor.

Merlin — The Poem

Many years after Geoffrey’s creation of Merlin in History of the Kings of Britain, Robert De Boron composed a poem titled Merlin based on the former’s story. However, Boron’s poetic rewrite of Merlin’s exploits emphasized the legendary wizard’s ability to change forms, connection to the Holy Grail, and goofy nature.

Merlin begins with the demon king scheming to destroy the world by sending a supernatural entity whose evil surpassed Christ’s good to the mortal plane. To achieve this, the creature must contain the genome of the demon spawn and humans — a devil halfling. And to that purpose, he chose to possess a wealthy believer to impregnate his daughter as a vessel.

With none being the wiser, the demon king’s plan went smoothly. The believer was successfully possessed, and the vessel was impregnated.

However, just when the supernatural resurrection plan was on the cusp of success, the daughter, who seemingly had been aware of her father’s possession, reported what transpired to her confessor, who then blessed her with the sign of the cross to protect her.

As a result, instead of having a supernatural child with an evil spirit, she will have a supernatural child free of any evil influence.

When Merlin was born, he was baptized. Besides the supernatural prowess that endowed him with skills in the magical arts, Merlin was also ‘good.’ The poem proscribed his inherently good nature to his baptism, his mother’s natural piety, and her confessor’s crucifix blessings.

Despite the complicated nature of his birth, young Merlin grew up in peace. That was until the usurper King Vortigern dispatched his goons to locate a fatherless kid to sacrifice for the stability of his tower’s foundation.

From here on, Robert’s narrative mirrors Geoffrey’s without a fault. From Merlin’s influence in Arthur’s birth, where he helped Uther — King Arthur’s father in urban legends — bed his enemy’s wife, the beautiful Queen Ygerne to his legends in Stonehenge. Post-conception, Uther handed Arthur to Merlin, who placed him with a foster family who did not know his royal lineage.

Arthur’s true identity was revealed later when he pulled the king’s sword from an anvil, proving himself as Uther’s son and heir.

While it might seem like he only retold existing mythology in his own narrative, that is not the case in reality. Robert was one of the key contributors, with his most significant contribution being the Christianization of the Arthurian tales.

The grail, once a platter, was now known as the Holy Grail, or the cup of Christ. Though still a side character, Merlin is now portrayed as a Christian prophet. Arthur and his knights similarly deviated from their original cast as noble warriors fighting for honor and country with Christ’s support to being Christ’s defender with all their exploits made possible because of their devotion to God.

Vulgate Cycle & Prose Merlin

Boron’s poem was eventually re-written(in old French) in prose in the early 13th century as part of the Vulgate Cycle series that focused on interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance.

In the Middle Ages, poetry was typically employed for imaginative works, while prose was reserved for works on “serious” subjects like history, religion, or philosophy.

Historians believe that the anonymous authors of the Vulgate Cycle prose at the time deliberately chose to retell these mythologies in prose format because they wanted to depict the subject as true history rather than fantastical romance.

The Holy Grail’s history is covered in the first part of the prose before shifting to Merlin’s birth and interactions with Arthur. It emphasized Lancelot’s relationship with Guinevere, drove up the significance of the knights’ search for the Holy Grail, and concluded with Arthur’s demise following the Battle of Camlann.

The Vulgate Cycle’s unprecedented depiction of Arthurian mythology as a piece of history inspired several works, the most significant of which was Estoire de Merlin, roughly translated as the Prose Merlin.

Estoire de Merlin dates back to the mid-15th century. The entire book, which was composed in Middle English, centers on Merlin as the main character and protagonist against the backdrop of the Arthurian mythical verse.

The Piece heavily underscored Robert de Boron’s Merlin in the general Arthurian storyline but significantly develops details relating to Merlin. For instance, the Estoire de Merlin details why the demon king wanted to spawn a demonic halfling with a human female.

Similar to how it’s told in the Bible, following Christ’s crucifixion, he barged into hell to release imprisoned souls — the Harrowing of Hell. Because of this tragedy, depending on your POV, the devils decided to create their own demonic messiah on earth to send as many souls as Christ freed back to hell, essentially counteracting Christ’s previous efforts.

Robert de Boron’s Merlin and the Prose Merlin’s reiteration of Arthurian mythology bears significant similarities for at least the first five sections of the latter. The divergence between the two stories of Merlin’s myth manifests in Estoire de Merlin’s later parts — the historical finale ( Prose Merlin Sequel) and the romantic finale (Suite du Merlin).

The historical finale picks the baton where Robert de Boron’s Merlin left off, with Arthur pulling the sword from a stone — as opposed to the anvil in Merlin — and then chronicles Arthur’s struggles with Camelot’s rebellious noble, the establishment of the court, and his exploits.

The romantic sequel, on the other hand, characteristically developed all the fantastical elements of Arthurian mythology, from Arthur’s acquisition of the Excalibur, to the creation of the round table, the illicit romance between Lancelot and Guinevere, and how Nimue — Merlin’s protege and lover — betrayed him condemning him to eternal death in limbo.

The major significant aspects of the Arthurian mythical verse are explored in this work; however, this wasn’t the final stop.

Merlin — Le Morte D’Arthur

Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur is the final historical stop in the development of the legendary wizard Merlin we’ve come to know today.

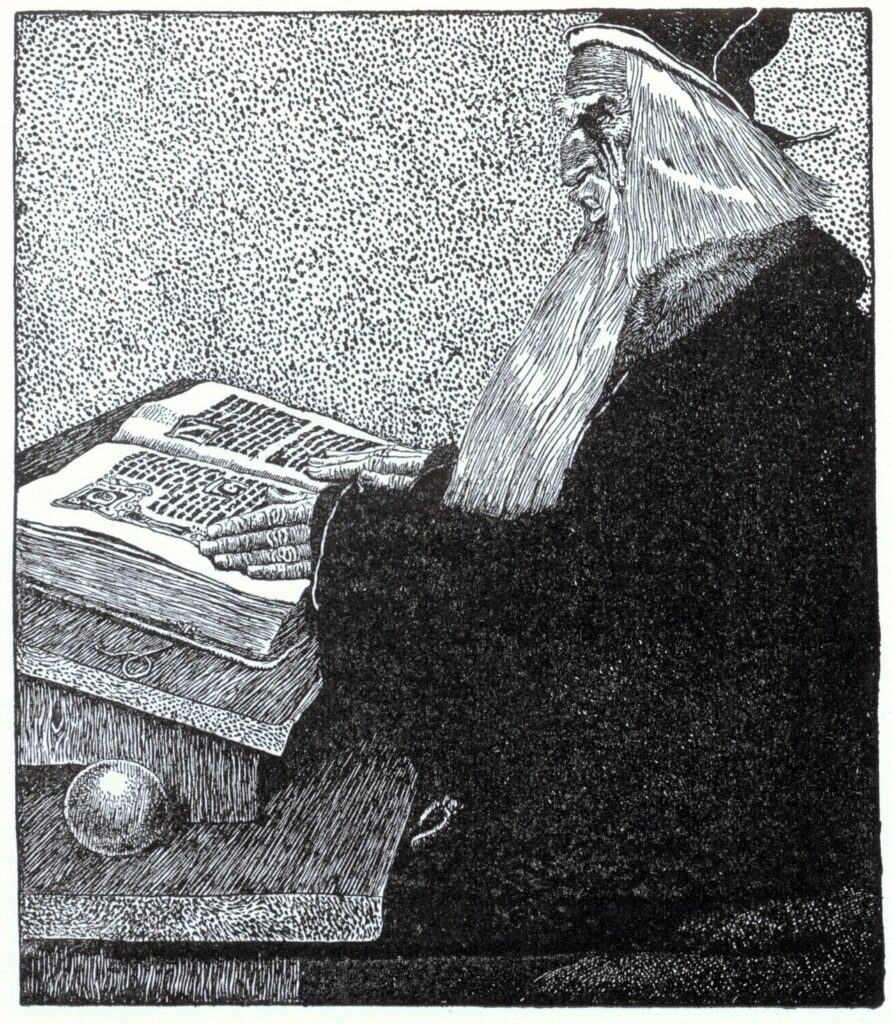

The Le Morte D’Arthur was the masterpiece Sir Thomas developed when he was a political prisoner at Newgate in London between 1468 B.C.E and 1470 B.C.E. This piece is the final culmination of all the prior historical versions of the seer — an all-powerful warlock wizard with prophetic abilities, able to shape-shift, manipulate others’ perceptions of reality, as well as read people’s minds and graphs their true desires.

As observed, Malory undoubtedly took inspiration from the Prose Merlin for the essence of his Merlin character but gave him a considerably richer development.

Like prior works, Merlin is the offspring of a noblewoman and a demon; he helps Uther conceive Arthur, and after baby Arthur is born, he places him with Sir Ector’s foster family. Arthur grew up and could pull the king’s sword from the stone, subsequently earning his place as heir to the throne of Camelot.

Merlin reappears in Arthur’s life after this event, counsels him on kingship and just rule, and remains an ever-present figure behind the scenes directing events or attempting to persuade others in the court and beyond to heed their better natures.

Other notable developments of Malory’s reimagination of the mythology included Merlin’s foretelling of Lancelot and Guinevere’s romantic betrayal, Merlin’s ill boded love story that ended in his eventual demise, the destruction of the round table, and the inevitable death of king Arthur.

Ultimately, Merlin remains one of ancient mythology’s most compelling fictional characters. Since his first appearance in Geoffrey’s History of the Kings of Britain, he’s impacted how people thought about wizards, magi, sorcerers, and wise men.

His influence remains even in a 21st-century storytelling culture. Numerous movies, video games, TV shows, books, and works of short fiction all contain references to the mythical magician. His persona permeates or shapes that of every wizard who has come after him, regardless of form, even when he is not explicitly referenced by name.