The Sphinx is a mythical creature with a human head and the body of a lion. In Greek mythology, the Sphinx also had the wings of an eagle.

The word ‘Sphinx’ comes to English from the Greek. Some scholars believe that this name comes from the Greek word for ‘squeeze’ – a reference to how lions kill their prey by taking the back of the animal’s neck in their jaws and squeezing until the animal is killed.

Other historians think that this word comes from an ancient Egyptian word that meant ‘living image.’ This is a reference to the Great Sphinx of Giza, which was carved in place from “living” stone rather than being transported and assembled in pieces.

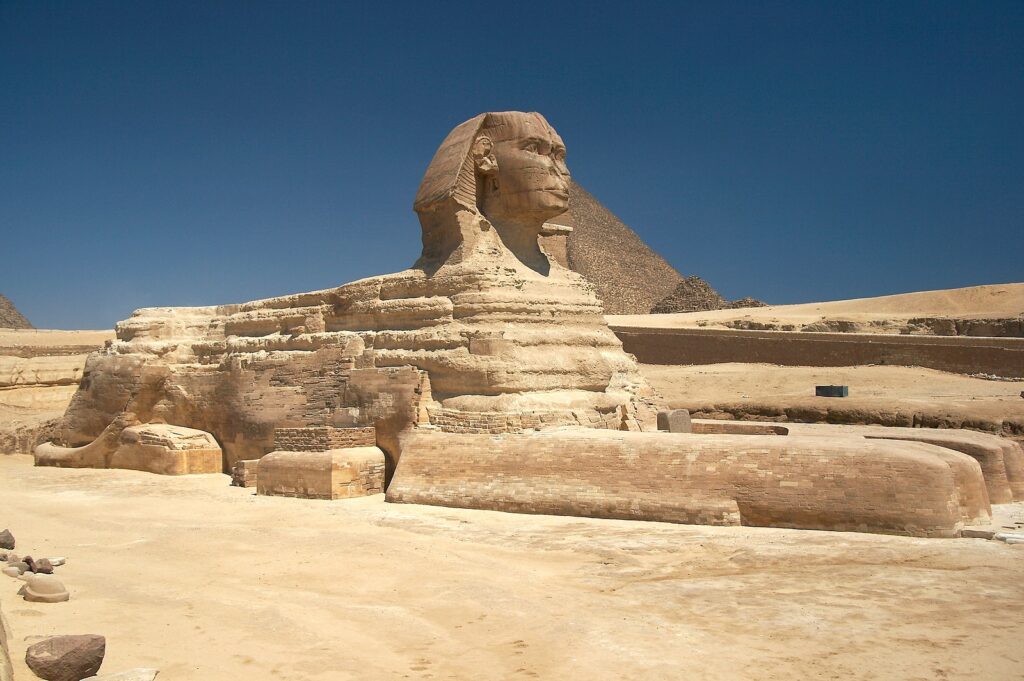

The Great Sphinx of Giza

The Sphinx is Egypt’s oldest monumental sculpture. Its face is thought to be a representation of the pharaoh Khafre, who ruled Egypt from approximately 2560 BC to 2535 BC.

This Old Kingdom pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty was responsible for the second largest of Giza’s pyramids. The Pyramid of Khafre is 448 feet tall and was built to house Khafre’s sarcophagus. Dozens of statues were made in his image, and more statues have been found of him than of any other Old Kingdom pharaoh.

Some Egyptologists say that the Sphinx was actually created by a lesser-known pharaoh named Djedefre, who was the half-brother of Khafre and the son of Khufu, who built the Great Pyramid of Giza. Others claim that the Sphinx was commissioned by Khufu himself.

The Sphinx is thought to be over 4550 years old. This famous limestone statue was originally chiseled in place out of bedrock. In subsequent years, limestone blocks were used for restoration purposes.

The original name for the Sphinx has been lost. A thousand years after it was built, Egyptians called it by the name of their sun god. A thousand years after that, Greeks began calling it the Sphinx.

The Sphinx in the New Kingdom

A few centuries after its construction, shifting sands buried the Sphinx up to its shoulders. Thutmose IV arranged for a team to excavate the statue’s front paws around the time that he became pharaoh.

During the New Kingdom (1550 BC to 1069 BC), the Sphinx was deified and worshiped as the sun god Horus. Eventually, a cult grew up around it, and temples were built nearby. Amenhotep II (1427 BC to 1397 BC) ordered a temple to be built nearby in honor of the sun god.

The Dream Stele commissioned by Thutmose IV when he became pharaoh in 1401 BC refers to the Great Sphinx of Giza as Hor-em-akhet, or ‘Horus of the Horizon’. This fifteen-ton granite block rests between the front legs of the Sphinx and originally served as the back wall of a small temple.

The Sphinx was excavated a second time by Ramesses II the Great (1279–1213 BC).

Over time and with influence from other regions, the god Horus morphed into Hauron. Even after this reimagining of their falcon god, Egyptians continued to associate the Great Sphinx of Giza with this popular deity. For a long while, the Sphinx was referred to locally by the name of Hauron.

The worship of Hauron died out around the time of the Persian conquest in 525 BC, but Egyptians continued to venerate the Sphinx. During the Middle Ages, it was believed to be a talisman that held the desert at bay and controlled the all-important flood cycle of the Nile.

The Sphinx in Ancient Greece

In Greek Mythology, the Sphinx was a terribly dangerous creature with the head of a woman, the body of a lion, the wings of an eagle, and sometimes the tail of a serpent.

It should be noted that the Greeks always wrote of the Sphinx as a foreign creature, often one that came from the regions around the Nile.

She was sent by the gods to punish those who had displeased them. She would devour men who failed to solve her riddles.

In some tales, she plagued the city of Thebes. In others, she guarded its gates. Anyone who wished to pass must answer her riddle, and those that failed would be devoured.

The Sphinx asked, “Which creature has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?”

Oedipus, the mythical king of Thebes, answered, “Man, who crawls on all fours as a baby, then walks on two feet as an adult, and then uses a walking stick in old age.”

Another ancient version of the story gives a different riddle: “There are two sisters: one gives birth to the other and she, in turn, gives birth to the first. Who are the two sisters?”

The answer to this riddle is Day and Night.

Once Oedipus beat her at her own game by answering the riddle correctly, she threw herself off of a cliff. Or, in other versions of the story, he killed her. In some, she devoured herself in the way she had devoured so many travelers.

The Sphinx in Greco-Roman Times

Ancient Greeks regarded the Sphinx as a fascinating historical artifact.

The statue was excavated in the first century, when Tiberius Claudius Balbilus was Governor of Egypt, and eventually became a popular tourist destination. A massive staircase nearly forty feet wide was constructed to give visitors a superior view of the Sphinx.

It seems that some of the statue’s original coloring may have survived those two thousand and five hundred years, because Pliny the Elder (23 AD – 79 AD) describes it as follows:

In front of these pyramids is the Sphinx, a still more wondrous object of art, but one upon which silence has been observed, as it is looked upon as a divinity by the people of the neighborhood. It is their belief that King Harmaïs was buried in it, and they believe that it was brought there from a distance. The truth is, however, that it was hewn from the solid rock; and, from a feeling of veneration, the face of the monster is coloured red. The circumference of the head, measured round the forehead, is one hundred and two feet, the length of the feet being one hundred and forty-three, and the height, from the belly to the summit of the asp on the head, sixty-two.

Pliny the Elder (23 AD – 79 AD)

Retaining walls around the Sphinx were restored in 166 AD and it was still visible in 200 AD. Following the fall of Rome, the statue was once again engulfed by sand.

Ancient Egyptian gods and the statue itself were still worshiped through the Roman occupation and even into Medieval times. This caused problems for the Sphinx, as we’ll see in a moment.

What happened to the Sphinx’s nose?

Popular myth says that the Sphinx lost its nose to cannonfire in 1798 when Napoleon invaded Egypt. In reality, the nose disappeared centuries earlier.

The Egyptian historian Taqī al-Dīn Abū al-‘Abbās Aḥmad ibn ‘Alī ibn ‘Abd al-Qādir ibn Muḥammad al-Maqrizi (born 1364) documented the Sphinx’s missing nose during his lifetime. Contemporary pieces of art also depict the statue without a nose.

Art sketched by the Dane Frederic Louis Norden in 1737 also shows the Sphinx without a nose.

According to al-Marqrizi, the nose was deliberately destroyed by Muhammad Sa’im al-Dahr when al-Marqurizi himself was just fourteen. The Sufi Muslim al-Dahr was outraged that local peasants were making offerings to the Sphinx. Therefore, he defaced the statue by removing the nose and damaging the ears. He was later executed for vandalism.

Archaeological inspections of the Sphinx confirm that the nose appears to have been removed deliberately using chisels and rods.

An Enduring Symbol of Antiquity

The Sphinx became a popular tourist destination again in the 1800s after it was once again excavated in 1817 to reveal its chest and paws.

Popular lecturer John Lawson Stoddard described it as an otherwise unimpressive statue that was marveled at simply for how long it’s survived:

It is the antiquity of the Sphinx which thrills us as we look upon it, for in itself it has no charms. The desert’s waves have risen to its breast, as if to wrap the monster in a winding-sheet of gold. The face and head have been mutilated by Moslem fanatics. The mouth, the beauty of whose lips was once admired, is now expressionless. Yet grand in its loneliness, – veiled in the mystery of unnamed ages, – the relic of Egyptian antiquity stands solemn and silent in the presence of the awful desert – symbol of eternity. Here it disputes with Time the empire of the past; forever gazing on and on into a future which will still be distant when we, like all who have preceded us and looked upon its face, have lived our little lives and disappeared.

John Lawson Stoddard

The Sphinx was repaired in 1930 to restore portions of the headdress that had been lost to erosion in the 1920s. Further restorations were done to the base and body of the statue in the 1980s and 1990s.

It remains one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world, with roughly four million people visiting the Sphinx each year.