In the realm of American folk music, no name is more significant than Woody Guthrie. He embodies the American spirit and epitomizes the struggle of the common man in the most trying of times.

Songs like, “This Land Is Your Land,” “Don’t Kill My Baby & My Son,” and “I’m Blowing Down That Old Dusty Road” are not just casual observations of the tribulations countless individuals faced at the turn of the 20th Century while in pursuit of the American dream.

They chronicle extraordinary events that may otherwise have been lost to the passage of time.

Yet despite his invaluable contribution to audio journalism, an indelible black mark besmirches Guthrie’s entry in our history books. Guthrie did something many considered the most un-American act possible: he criticized the American government and allowed himself to be labeled a Communist.

Early Years

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born on July 14, 1912, in the small agricultural and railroad town of Okemah, Oklahoma. This bordered the newly relocated Creek Nation. He was the third of five children born to Charles and Nora Belle Guthrie.

Both of his parents were musically inclined. But it was his father (a former cowboy, land speculator, and local Democratic politician who named his son after President Woodrow Wilson) who taught Guthrie how to play and sing.

He taught him Western, Native American, and Scottish folk tunes. His mother introduced all her children to a wide variety of music, and no doubt influenced Guthrie’s unique, folksy style.

In the early 1920s, oil was discovered in the county. It brought a sense of prosperity that the people of Okemah had never known.

Within a decade, however, the oil all but ran out and the town plunged into decline. This left the town worse off than before.

Guthrie, now in his teens had to deal with his family’s financial ruin. He also had to cope with the accidental death of his older sister, Clara.

This was followed by the mental decline of his mother. She suffered from Huntington’s Disease and had to be institutionalized. (Huntington is a hereditary neurological disorder that came to affect Guthrie himself in his later years.)

These events colored Guthrie’s view of the world and the first songs he wrote.

Texas

In 1931, the 19-year-old Guthrie left Oklahoma for the Texas panhandle. He settled in the town of Pampa.

There he fell in love with Mary Jennings, She was the younger sister of fellow musician Matt Jennings, with whom Guthrie (along with Cluster Baker) would form his first band, The Corn Cob Trio. They were later renamed the Pampa Junior Chamber of Commerce Band.

Guthrie and Mary married in 1933 and together had three children: Gwen, Sue, and Bill.

It was also while living in Pampa, Texas, that Guthrie discovered his talent for drawing and painting. This was an interest he would pursue throughout his life.

Hard Times

Still in the throes of the Great Depression (1929-1939), Guthrie had a difficult time keeping his family fed. This was even before the onset of the great dust storm and so-called “Dust Bowl,” which hit the Great Plains in 1935.

Drought and dust forced tens of thousands of desperate farmers and unemployed workers from Oklahoma, Kansas, Tennessee, and Georgia to head west, where they’d heard work was abundant. Like all the other “dustbowl refugees,” Guthrie hit Route 66–and left his family behind.

Flat broke and starving, Guthrie walked, rode the rails, and caught rides with passing cars and trucks headed to California. He took whatever small jobs he could finagle along the way.

In exchange for a bed and some food, Guthrie put his two talents to work. He painted signs for business owners and played guitar in saloons.

In the process, Guthrie developed a love for the open road. It was a sense of wanderlust that would both benefit and hinder his personal and professional life.

California or Bust

By the time Guthrie arrived in California in 1937, he was battered and discouraged. He experienced an ugly side of human nature he’d never imagined.

The victim of intense contempt and hatred from Californians who opposed the massive migration of “Okies,” he’d endured continual physical threats. He also nearly ended up in jail.

Upon reaching Los Angeles, Guthrie got his first big break. It was singing “old-time” traditional songs (as well as his originals) on KFVD radio.

Teamed with singing partner Maxine “Lefty Lou” Crissman, Guthrie began to attract a widespread audience, particularly from among the thousands of displaced “Okies” gathered in nearby migrant camps. They lived in makeshift cardboard and tin shelters.

Guthrie’s down-home music provided a pleasant distraction and nostalgic connection to the life many had left behind. His music was a respite from the harsh realities of migrant life. It was a tonic for the loved ones left behind.

But more than just a forum to share his home-spun folk songs, the airwaves provided Guthrie a podium from which to develop his budding gift for controversial social commentary and criticism. He had an opinion–and didn’t hesitate to voice it.

A Voice in the Wilderness

From corrupt politicians, dishonest businessmen, and crooked lawyers hiding behind the “do-unto-others” principles of Jesus Christ–to union organizers fighting for migrant workers’ rights in California’s agricultural communities–to the outlaw hero Pretty Boy Floyd–Guthrie proved himself an outspoken, straight-talking, advocate for justice and human rights.

Guthrie closely identified with the downtrodden. He spoke his words and sang his songs to the everyday man.

This would soon became an essential element of his social and political standing. It was an element that soon found its way into songs like, “I Ain’t Got No Home”(1940), “Talking Dust Bowl Blues”(1940), “Tom Joad”(1940), and “Hard Travelin’”(1946).

More than just sociopolitical messages set to music, his songs became national anthems reflecting his desire to give voice to those who’d been disenfranchised. Disheartened. Feeling alone.

The thousands of displaced men, women, and children who felt abandoned by the American government.

Avoiding and Chasing Success

Guthrie was never comfortable in the limelight. Because of this feeling and combined with his growing wanderlust, Guthrie left California for New York City in 1940. This is where he discovered an audience he never imagined

He came into contact with the grass roots of what would later become the “Beat” social movement. It consisted of artists, writers, anarchists, musicians, and progressive intellectuals who were immediately drawn to Guthrie’s “authenticity” and down-home wisdom.

In February of 1940, Guthrie wrote his most famous song, “This Land Is Your Land.” It is said to have been an angry response to Irving Berlin’s, “God Bless America.”

Guthrie thought Irving’s lyrics Guthrie were unrealistic and complacent. (Although “This Land” was written in 1940, it would be four more years before he would record it, for famed record executive Moses Asch.)

The following month, Guthrie was invited to appear at a benefit hosted by the John Steinbeck Committee to Aid Farm Workers, to raise money for down-and-out migrant workers. There he met folk singer Pete Seeger.

The two men became fast and loyal friends. (Seeger even accompanied Guthrie back to Texas to meet the other members of the Guthrie family.)

That same year, American ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax (best known for his numerous field recordings of folk music of the 20th Century) recorded Guthrie in a series of conversations and songs for the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Guthrie then recorded a collection of songs for RCA Victor Records given the title, Dust Bowl Ballads. It was his first official album of original songs.

This set in motion a decade-long frenzy to record Guthrie’s homespun, controversial folk songs. Hundreds of songs were committed to wax for Moses Asch’s Asch/Folkways Record labels.

To this day, these recordings remain the benchmarks for folk music singer-songwriters around the world.

The New York Years

While living in New York City, Guthrie’s circle of close friends and collaborators (both music and political) included Pete Seeger, “Lead Belly,” Brownie McGhee, Sis Cunningham, and Burl Ives—to name just a few.

Forming a loosely knit, collaborative folk group called The Almanac Singers, they pooled their resources for social causes like union organizing, anti-Fascism rallies, and speaking out for civil rights (which had the effect of strengthening the Communist Party), through activism and singing songs of political protest.

Guthrie became one of the most prolific songwriters for this group.

(In the early 1950s, The Almanacs re-formed as The Weavers. They became the most commercially successful and influential folk music group of the era. It was through their extraordinary popularity that Guthrie’s songs came to be known to the public at large.)

Beginning in April of 1940, Guthrie and Seeger shared a loft in Greenwich Village owned by controversial sculptor Harold Ambellan. By this point, Guthrie’s popularity had gotten him invited to guest-star on CBS radio’s Back Where I Come From.

He used his influence to secure a spot on the show for his friend Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter.

In September of that year, Guthrie was invited by the Model Tobacco Company to host their radio program, “Pipe Smoking Time,” for which Guthrie was paid an impressive $180 a week.

In November of 1941, Seeger introduced Guthrie to poet Charles Olson. Olson was then a junior editor at a new quarterly literary magazine called Common Ground (published by the Common Council for American Unity).

Guthrie penned an article called “Ear Players” for the Spring 1942 issue. This marked Guthrie’s debut as a published writer in mainstream media.

With increasing popularity, prosperity, and critical acclaim (from public performances, recordings, and radio shows), Guthrie could finally afford to bring his struggling family from Texas to New York City to share in his new-found success.

Restless and Disillusioned

Despite Guthrie’s commercial and popular success, the realities of the media and entertainment business were constant reminders of the limitations he faced in getting his message out. The airwaves, through which he could reach thousands of listeners, were nonetheless subject to censorship. As were his words and music.

Frustrated, Guthrie left New York with his wife and three children and headed for Portland, Oregon. There, a documentary about the building of the Grand Coulee Dam was underway. Film director Gunther von Fritsch had extended an offer to Guthrie to contribute his songwriting talent to the project.

Guthrie was placed on the payroll of the Bonneville Power Administration (the federal agency that supplied power to the Pacific Northwest) for a month. During this time he, composed the Columbia River Songs.

This was an extraordinary collection of songs that included, “Roll on Columbia,” “Grand Coulee Dam,” and “The Biggest Thing That Man Has Done.”

With his contract fulfilled, Guthrie moved his family back to Pampa, Texas, then headed to New York City alone. By this point, his constant traveling, performing, and lack of consistent income began to take its toll on his wife and family.

This—combined with his involvement with progressive “radical” politics–helped bring about the end of his first marriage.

More and more, Guthrie’s personal views were being seen as extremist rather than patriotic.

A World At War

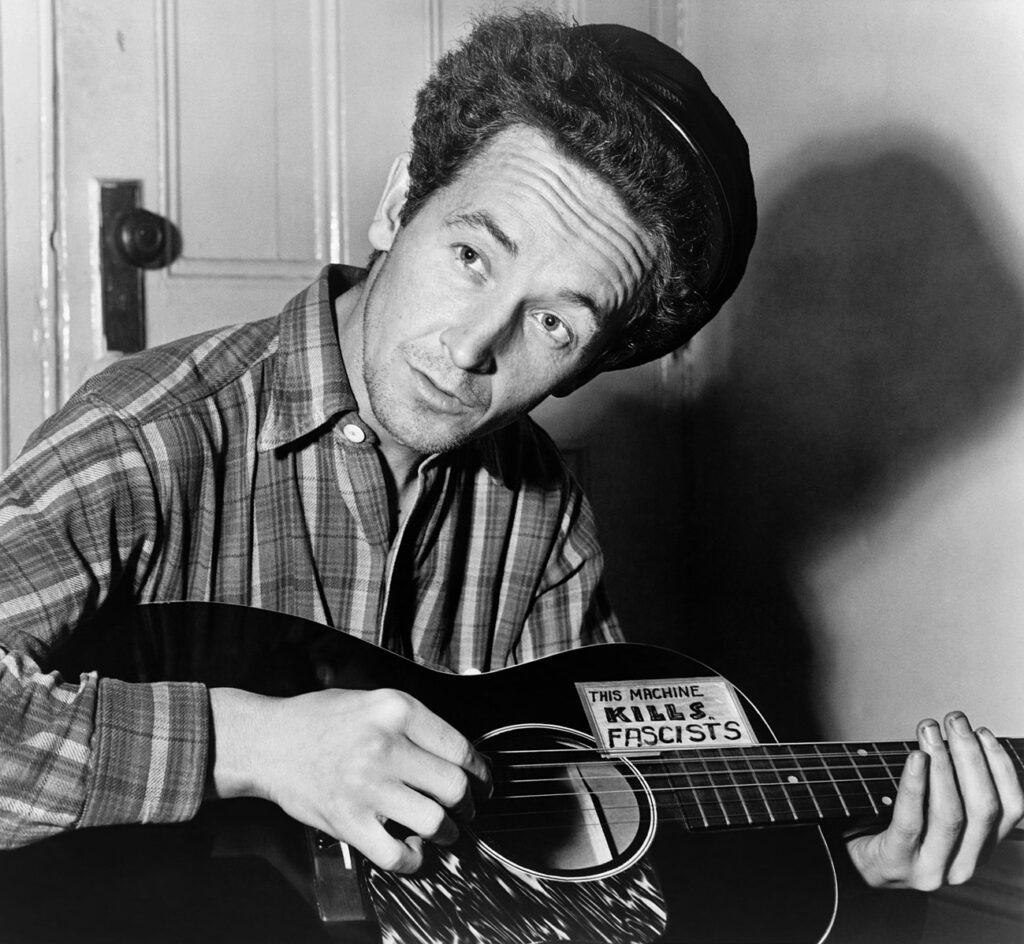

In June of 1943, Guthrie joined the US Merchant Marine. He began composing songs with a more blatant anti-Fascist message. (The guitar Guthrie used on stage bore the slogan, “This Machine Kills Fascists.”)

Guthrie had originally lobbied the US Army to accept him as a USO performer rather than conscript him as a soldier. When that failed, he joined the Merchant Marine instead.

As such, he made several voyages aboard a number of merchant ships including the SS William B. Travis, SS William Floyd, and SS Sea Porpoise. He served as a mess hall worker and dishwasher while the ships traveled in convoys during the Battle of the Atlantic.

(Guthrie, of course, frequently sang for the crew to raise their spirits during the long transAtlantic voyages.)

While on furlough as a Merchant Marine, Guthrie met and married Marjorie Greenblatt Mazia. However, he was still legally married to his first wife.

After the War, he and Marjorie bought a house on Coney Island, New York, and had four children together: Cathy, Arlo, Joady, and Nora.

Though Guthrie had written over 100 songs by this point, Guthrie himself considered this his most musically prolific period. He continued to pen powerful political anthems while also writing children’s classics like, “Don’t You Push Me Down,” “Ship In The Sky,” and “HowdiDoo.”

Allegations of Communist Sympathizing

With the official release of “This Land is Your Land” (in 1945) came allegations that Guthrie’s politics ran towards the “red,” and that he was likely a Communist sympathizer.

He’d made no secret of his anti-Fascist sentiments. He opposed the far-right, authoritarian, political movement in Europe, characterized by dictatorial leadership.

He was vocal about believing in socialism. He had also met with Ed Robbin, a writer for Peoples World (the Communist Party’s West Coast newspaper), while working at KFVD radio.

And it was widely known that one of the first things Guthrie did after meeting Robbin, was write a song about Tom Mooney. Mooney was a labor organizer who’d been imprisoned for allegedly bombing a “Preparedness Day” parade in 1916.

This parade was held in preparation for the US entering World War I. Mooney remained imprisoned until 1939. Guthrie’s response to his release was the partisan song, “Tom Mooney is Free.”

A more damning example of his partisanship came in the song, “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?” He wrote this in response to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s berating members of a youth rally (which included communist sympathizers) held soon after the USSR declared war on Finland.

At issue were lyrics that appear to echo an anti-war stance consistent with the Communist Party’s slogan, “The Yanks Aren’t Coming” — a position they held during the non-aggression pact between Germany and the USSR.

To many Americans, it appeared that Guthrie had incorporated the Communist Party’s perspective into his lyrics when he wrote what would become, “This Land is Your Land.”

Listeners noted that Guthrie’s song doesn’t extol God’s special relationship with the United States (“God Bless America”). Instead, it asks how it could be that He blessed a country where people were out of work, starving, and standing in relief lines like beggars.

Even his long-time supporters began to question whether they’d misjudged his loyalties from the start.

His Final Years

By the late 1940s, Guthrie’s health was in serious decline. His behavior was uncharacteristically erratic.

After a number of incorrect diagnoses (including alcoholism and schizophrenia), in 1952 it was finally determined that he was suffering the same disease that had devastated his mother: Huntington’s.

Believing him to be a danger to their children (because of his unpredictable behavior), his second wife, Marjorie, suggested he return to California without her. Once there, she divorced him.

Upon his return to California, Guthrie was invited to live at the Theatricum Botanicum. This was a repertory theater (of sorts) founded and owned by actor Will Geer, in Topanga, California.

It was established specifically for actors, musicians, and other artists blacklisted during the so-called “Red Scare,” (labeled Communist sympathizers).

While Guthrie’s health continued to deteriorate, he met and married his third wife, Anneke Van Kirk. They moved to Fruit Cove, Florida, where they lived in a converted bus and had one child, Lorina Lynn.

In 1954, the couple moved to New York City and rented an apartment in the Beach Haven Apartment complex. Shortly afterwards, Anneke filed for divorce, no longer able to care for her husband.

At this point, Guthrie’s second wife, Marjorie, re-entered his life and cared for him until his death.

Increasingly unable to control his movements, Guthrie was hospitalized at Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital in Morris County, New Jersey, from 1956 to 1961. Then, at Brooklyn State Hospital (now Kingsboro Psychiatric Center) in East Flatbush until 1966.

He ended up at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens Village, New York, where he would finally succumb to the final stages of Huntington’s in 1967.

Woodrow “Woody” Guthrie died on October 3, 1967, at the age of 55.

Living Legacy

Today, Woody Guthrie’s son, Arlo, carries on the Guthrie name, fame, and songwriting legacy.

References

archive.org, Woody Guthrie, American Radical, https://archive.org/details/woodyguthrieamer0000kauf

archive.org., Woody Guthrie: a Life, https://archive.org/details/woodyguthrielife0000klei

biography.com., “Woody Guthrie,” Woody Guthrie: Biography, Folk Musician, Children, Songs & Guitar

archive.org., Bound For Glory, https://archive.org/details/boundforglory0000guth

archive.org., Hard Travelin The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie, https://archive.org/details/hardtravelinlife0012robe

historynewsnetwork.org., “Woody Guthrie’s Communism and ‘This Land Is Your Land,’” Woody Guthrie’s Communism and “This Land Is Your Land” | History News Network

archive.org., The life, music, and thought of Woody Guthrie : a critical appraisal, https://archive.org/details/lifemusicthought0000part