Last updated on March 7th, 2024 at 02:03 am

Frankenstein may have had a kindred spirit with Soviet scientist Vladimir Demikhov.

In 1954, Demikhov successfully grafted the head of a smaller dog onto the neck of a larger one, essentially creating a two-headed dog.

A few years later, in 1959, LIFE magazine visited Demikhov to document what would be the 24th of his creative experiments on canines.

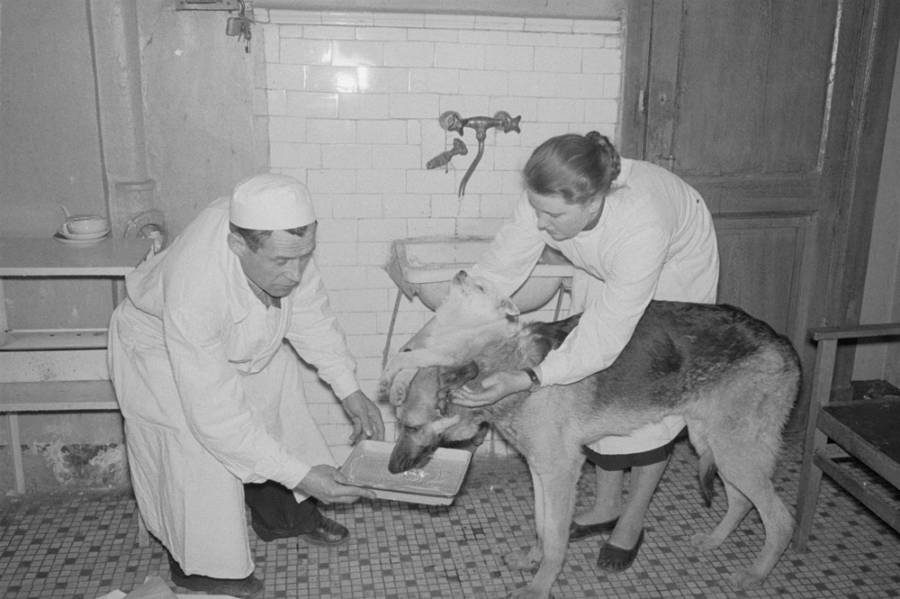

The LIFE team reported in detail the gruesome operation. After Demikhov prepared the dogs for surgery, he carved down through the smaller one, Shavka’s, flesh to her vital organs.

Next, he severed her spine. The magazine article then picks up with this description:

“Although the rest of the body had now been amputated, Shavka’s head and forepaws still retained and used the lungs and heart. Now began the third and most critical phase of the transplantation. The main blood vessels of Shavka’s head had to be connected perfectly with the corresponding vessels of the host dog. Demikhov severed the small dog’s arteries and, with a surgical stapling machine which is the Russian’s special invention, swiftly spliced them into the exposed vessels in Brodyaga’s neck. Shavka’s own heart and lungs were then cut away.”

This nightmarish process resulted in a dog with an extra head that could eat and swallow but little else.

The head was not connected to the rest of the larger dog’s organs, so all the food that the extra head ingested had to be pumped through a tube and discarded.

Demikhov had proven that he could turn two healthy dogs into one bizarre-looking dog with a virtual death sentence (the longest living of Demikhov’s dogs lasted one month). But why did he do it?

Hearts and Heads: Vladimir Demikhov’s Strange Experiments

Although Shavka and Brodyaga (the larger dog) only survived for four days, they fared better than many of their predecessors, who quickly died. Overall, Demikhov made at least 20 head grafts throughout his career.

His work, however, began with hearts.

In 1946, Demikhov began adding an extra heart to dogs to see if it would continue pumping blood.

Although these second hearts only lasted a few months, he considered the experiments a success. He then wanted to test how much of a dog’s body a single heart could sustain, essentially doing the opposite of the previous heart experiments.

To that end, he began grafting whole front ends of dogs onto his experimental victims. Shavka and Brodyaga were part of those efforts.

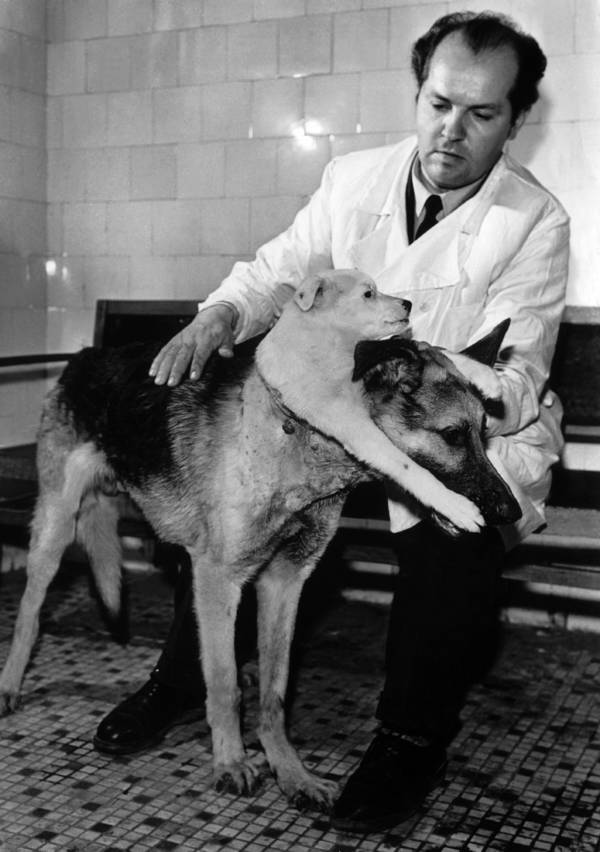

The most successful of Demikhov’s head grafts was undoubtedly a German Shepard named Pirat, who lived for a whole month as host to a smaller dog’s head.

Demikhov was happy to note that the passenger’s head acted independently of the German Shepherd host, occasionally biting and nibbling Pirat’s ear.

If you’re wondering whether Demikhov had a guilty conscience about what he was doing to his dog subjects, he makes it pretty clear that he lost no sleep over the experiments.

He claimed that “The big dog doesn’t understand” and that “he feels some kind of inconvenience, but he doesn’t know what it is.” He even joked that Brodyaga was a lucky dog because “You know the saying: two heads are better than one.”

Clearly, Demikhov wasn’t too concerned about the plight of his test subjects. But he wasn’t just carrying out these experiments as a cruel joke. He genuinely wanted to make organ transplants more effective in order to help accident victims who rely on these risky operations.

In this, Vladimir Demikhov may have indirectly saved the lives of innumerable transplant survivors.

Vladimir Demikhov May Have Been Ahead of His Time

Despite the macabre nature of his experiments, Demikhov had a very good reason for conducting them. His goal was to help advance the science of organ transplants. But, ultimately, he wanted to save lives.

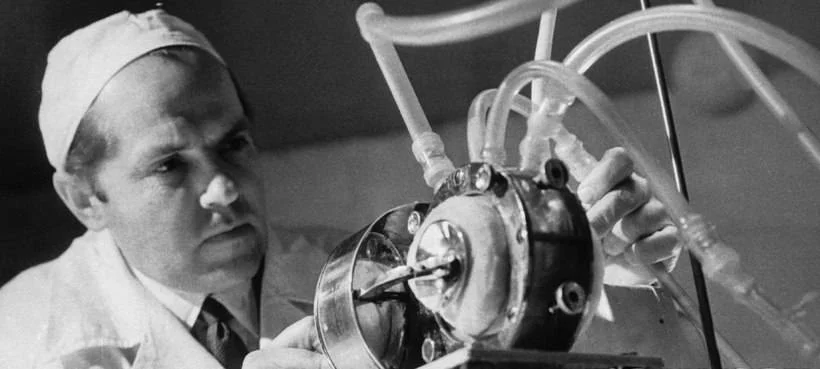

Vladimir Demikhov’s creativity began early. In 1937, when still a student at the University of Moscow, he invented a machine that could act in place of a heart and keep the body sustained with blood for up to five hours.

It may not sound like much, but in those decades, this was a significant step forward.

During World War II, Demikhov was called to serve as a pathologist in a field hospital.

Part of his job included evaluating injured soldiers to determine the cause of their injuries. You see, it was not uncommon for soldiers to shoot themselves to escape the front lines and spend the war in a hospital.

The punishment for being caught faking an injury, however, was death. Demikhov saved many lives by lying about the nature of many soldiers’ self-inflicted injuries.

After the war, Demikhov returned to his experiments. By 1946, he managed to perform the transplantation of a heart and both lungs, which had never been done before.

But then, during the 1950s, the Ministry of Health looked into Demikhov’s experiments and decided they were unethical.

That could have been the end of Demikhov’s research; however, his boss at the Moscow Institute of Surgery was the chief army surgeon and thus was able to sidestep the ministry’s directive.

Demikhov continued on, and in 1953 he had his first successful coronary bypass surgery. It gained little attention. His first canine head transplant, which he performed the following year, got people’s attention.

When the media caught wind of Demikhov’s unusual experiments, he immediately became the target of journalists, activists, and other medical professionals. His work, besides being seen as cruel, has no apparent possible real-world application.

However, others did see value in what Vladimir Demikhov was doing. As unsavory as his work may seem, his experiments were an important step toward figuring out how to carry out human transplants.

Many of the techniques that he pioneered on dogs during the years of the Cold War have now become standard practice in hospitals around the world.

In 1967, the South African doctor Christian Barnard was the first to carry out a human-to-human heart transplant successfully.

Years later, he acknowledged a debt of gratitude to Demikhov, saying, “I have always maintained that if there is a father of heart and lung transplantation, then Demikhov certainly deserves this title.”