Leading up to the first World War, many major world powers increased their colonial holdings worldwide. Then, in the late 1800s, many major world powers began to move into areas they had not colonized during the Age of Expansion.

This was partly fueled by the rise of the factory and the possibility of selling products in new markets that were not as accessible before the invention of steam-powered vessels.

Africa found itself at the epicenter of this scramble for territory and power, and the Scramble for Africa took place over a relatively short period.

From 1881-1914, European control expanded from 10% of Africa to nearly 90%. This led to a social and economic domino effect, which is still felt today in modern Africa.

Who Colonized Africa During This Scramble for Territory?

The Scramble for Africa is also known as the Partition of Africa or the Rape of Africa. It is important to remember that this period was a time of invasion and conquest, which Africans were not equipped to resist.

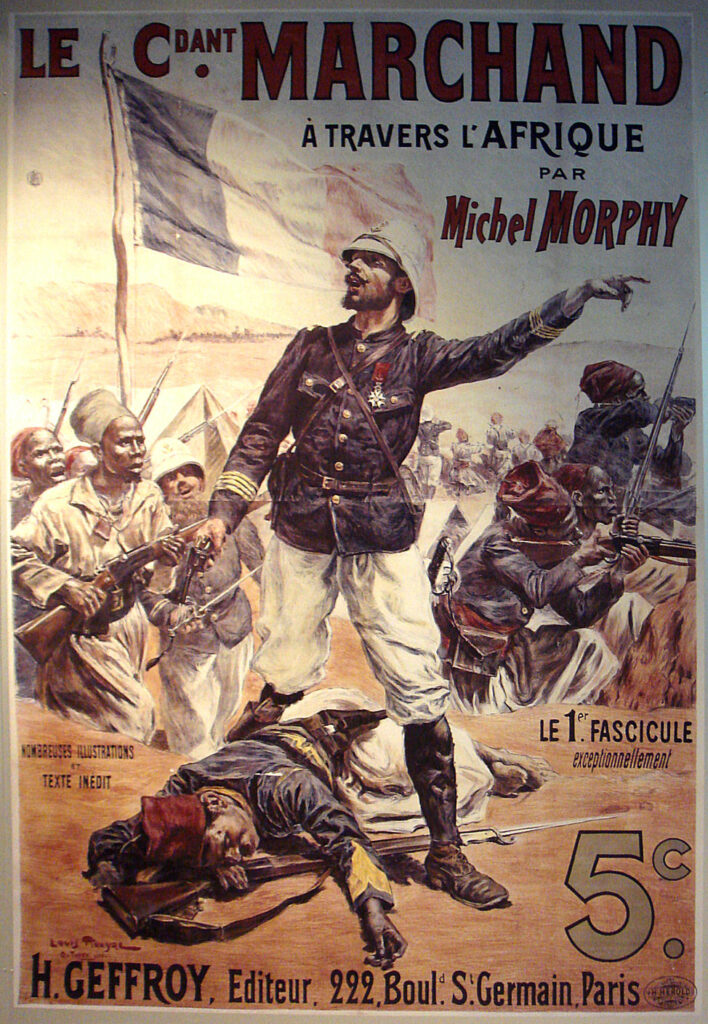

The contemporary histories which talk about this activity paint the actions taken by Europe in a positive light and act like the conquest of the entire continent were made to open up trading routes and new markets for Europe.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 is traditionally marked as the beginning of the Scramble for Africa. During this period, Belgian, British, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish powers raced against one another to colonize as much of the continent as possible. Only Liberia and Ethiopia remained independent by 1914.

The Portuguese were some of the first colonizers of the African continent (The Scramble for Africa, 2022). They had established a presence in the fifteenth century and were still a player in the colonizing race when the Scramble began.

The coastal areas of Africa had been the main focus of attention for colonizers up to this point, but Africa’s richest raw materials were inland. Being largely land-locked, most of Africa’s wealth was not guaranteed to be easily accessed unless a colonial power had ready access to a coastal outlet.

The Scramble grew heated when it became clear that a coastal holding was essential for those looking to profit from Africa’s wealth. Without a coastal territory under its control, no world power could export or import anything to its inland territories.

Without this factor, the race for Africa would likely not have been as desperate and might not have been completed so rapidly.

Building Connections to Inland Territories

Inland territories that were protected from the incursion of invading Europeans, up to this point, suddenly found their homes taken from them, their governments toppled, and railroads built across their native lands.

The Ashanti, Fulani, Tuareg, Opobo, Nbele, and Shona attempted to fight off the invading Europeans but were unsuccessful.

The Africans enjoyed more success in Northern Africa, where Italy worked hard to control Ethiopia. However, Italy could only control Ethiopia briefly before losing control of the territory again.

Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia and Libya still created social upheaval and strife, despite their short time in control of this part of the African continent.

Most of the world powers struggling over land in Africa were also worried about creating forts and military bases in their newly-acquired territory. Ships driven by steam power required coaling stations and protection while loaded and unloaded.

This meant that sea bases with military protection were a mandatory accessory to the invasion process. In addition, land trade routes also required protection, and the European powers created military outposts in every territory they held (Papaioannou, 2016).

The colonizing forces squabbled and argued over territory without consideration for the native population whose homes they had overtaken.

Britain and France held a large portion of the continent, but their territories were not always conjoined. Trade partnerships between these world powers were tenuous but essential to move products across territories that belonged to other nations.

Connections With the First World War

The race to overtake one another in Africa led to hurt feelings, anger, and resentment among the world powers trying to expand their economies across the globe.

Colonization had always been a source of strife amongst European powers, but colonization at home on your own continent was a messier and much more delicate process.

Large-scale competition over land that did not directly border the place you called home allowed for a sense of reckless abandon that had not been present in previous colonization efforts.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 attempted to mediate imperial sparring over the continent of Africa. Otto von Bismarck called for the convention, and the result of this conference was the first mapping of the presence of Europe in Africa to stay.

The European parties who attended the conference divided up the continent at this gathering without any thought to the people who called the continent home.

By the time decolonization was required, reluctant withdrawals by the European powers had led to power vacuums, unstable local economies, and the destruction of the social fabric which had been present before the invasion of Europe.

The destruction of the African continent, which took place following the Berlin Conference of 1884, is still felt today.

It is hard to know what Africans might have been able to achieve if Europe had not forcibly overtaken their continent and stripped it of resources while also destroying its economy and social stability (New World Encyclopedia, 2022).

Why Was the Colonial Period Handled in This Manner?

To a modern audience, it can seem brutal and authoritarian that European colonizers would take land away from the people who owned it and strip it of its resources for their gain.

While greed was certainly a motivating factor in the expansion into Africa, other pressures and social conventions in play led to these outcomes as well.

During the early industrial era, no check was placed on the ability to make money, seek profits, or look for personal gain if it could be accessed. The modern factory made work that had been slow, painstaking, and expensive suddenly very easy.

Best of all, cheap labor was everywhere if you were a factory owner. New technologies like steam power made factories run even faster, and travel across the globe had become much easier with steam-powered vessels.

The world had shrunk exponentially, and Europe could come into contact with new peoples they did not understand and disregarded completely.

To the myopic view of Europeans of this era, continents that did not have factories, the same kind of economy as theirs, or the same kind of cities and homes were uninhabited.

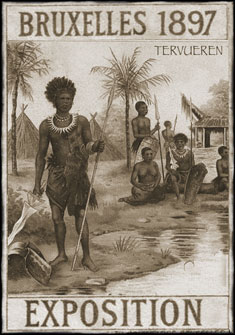

Industrial might and technology were considered required factors for a society or a culture to be worthy of respect. African tribal peoples met none of these requirements and were quickly disregarded and thrust aside by invading European powers.

This sad tale has been played out repeatedly throughout human history, but the Rape of Africa is perhaps one of the most acute instances of this kind of colonization abuse. Europeans called Africa “The Dark Continent” because it was felt that the continent was unknown and also empty and free for the taking (The Scramble for Africa, 2022).

A slightly darker connotation became the sense that the people who populated Africa were ignorant non-humans who required the assistance of educated Europeans to save them from their childish ways.

The Lasting Impact of the Scramble For Africa

As with all colonization efforts, the damage done to Africa is hard to overstate. Not only were terrible things happening to those left behind in Africa, but slavery and the display of African people in European zoos became commonplace after the close of World War I.

Social Darwinism and the misuse of anthropological concepts aside, the damage to the African continent was severe. Borders that had existed between tribes of African peoples had been utterly destroyed during the time of colonization.

This created ethnic partitioning which led to civil conflict and power vacuums that could not be readily filled once Europe pulled back from areas they had formerly controlled.

Political violence in places like Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Nigeria continues today in the wake of colonization. Due to the damage to local economies, Africans have inherited the same need Europeans had to control the coastal regions of the continent.

This has led to issues with civil unrest that was not an issue before the colonization period. Areas in the middle of the continent that were stripped of resources and whose economies were destroyed have never been allowed to fully recover due to the need for a seaport to survive.

Post-colonization Africa is at the mercy of world markets for resources in ways that it never was before the colonial period (Elias Papaioannou, 2017).

Another impact of the colonial period is that the redrawing of the lines between different African states has led to some areas being almost entirely bereft of the essentials needed to sustain life or any form of an economy.

When Europe held these areas, they could bring the necessary supplies back and forth across the territories that were held by other European powers as needed. This is not the case now that Africa is without these trading networks, which might move goods and essentials from one side of the continent to the other.

Native Africans who are trying to rebuild their country from scratch do not have the benefit of the natural territory boundaries which were established before Europe’s incursion. These natural boundary lines for territories were not arbitrary.

They were often established to allow each group who lived in that region access to the resources and essentials necessary for survival.

By redrawing the map of Africa in the image of Europe, European invaders brought with them the social strife and resource management issues that plagued their own countries across the ocean.

The Scramble for Africa Gave Birth to World War I and Led to Lasting Civil Strife in Africa

There are many things that the Scramble for Africa can be blamed for. Sewing the seeds of the conflict that would lead to the first World War is the first, but the complete destruction of the stability of the African continent is likely the more lasting of the legacies of this period of colonization.

The Scramble for Africa was born of the innate racism and opportunistic greed of Europe’s world powers both before and after World War I.

Without the negative impacts of the Scramble for Africa, the people of Africa might have been able to establish a stable economy and attend to instances of civil strife without all-out war.

Generations of Africans have suffered at the hands of the Europeans who took Africa by force in the late 1800s.

Present-day Africa is burdened by a legacy of destruction, racism, and economic ruin that can be traced back to the Scramble for Africa and the early Industrial period in Europe.

Sources

Scholar Blogs. “The Scramble for Africa.” https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/violenceinafrica/sample-page/the-scramble-for-africa/#2.0. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

Michalopoulos, S., Papaioannou, E. (2016). Scramble For Africa And Its Legacy, The. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_3041-1

New World Encyclopedia. “Berlin Conference of 1884-85.” https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Berlin_Conference_of_1884-85. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

New World Encyclopedia. “Scramble for Africa.” https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Berlin_Conference_of_1884-85. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

St. John’s College. “Scramble for Africa.” https://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/library_exhibitions/schoolresources/exploration/scramble_for_africa. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

Farah Nayeri. “Remembering the Racist History of ‘Human Zoos.’” 29 Dec. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/29/arts/design/human-zoos-africa-museum.html. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.

Stelios Michalopoulos, Elias Papaioannou. “The Contemporary Shadow of the Scramble for Africa.” 1 Mar. 2017, https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/contemporary-shadow-scramble-africa#:~:text=The%20Scramble%20for%20Africa%20has,of%20the%20newly%20independent%20states. Accessed 6 Jan. 2023.