The significance of the 9 am to 5 pm work day is partially a matter of circumstance. Thanks to the sun’s rising and setting, these times make sense when determining a standard beginning and end to an eight-hour work day.

Of course, we know that many people work different hours than this, but most people still work eight-hour shifts five days a week in the United States.

This was not always the case, and it might be surprising to find out just what it took to demand an eight-hour day for reasonable pay, how hard the fight was, and how some people even lost their lives in the battle.

The Early Origins of a Shorter Work Day

During the early years of the US, most people worked on their own farms or were what we might consider self-employed. However, by the 1830s, this was beginning to change.

Still, workers were expected to work from sun-up to sundown six days a week, with a day of rest on the Sabbath.

Yet in 1833, a group of labor organizers formed the General Trade Union (GTU) in Philadelphia and made the unprecedented move of including unskilled workers in their organization.

Two years later, coal heavers went on strike to demand a ten-hour day. As they marched through the city, others joined their cause.

The GTU printed posters and organized parades, and soon, 20,000 workers, including city employees, joined the strike.

The general strike proved successful, and many employees received their ten-hour work days and raised wages. Once their demands were met, the GTU gradually disintegrated.

Albert Parsons Fights for the eight hour work day

By the 1860s, workers were arguing for an eight-hour work day, as 10 hours was still too harsh in many industries. This movement steadily grew.

Things came to a head in May of 1886 when the leader of the Chicago Knights of Labor, Albert Parsons, led 80,000 workers through the streets demanding an eight-hour workday.

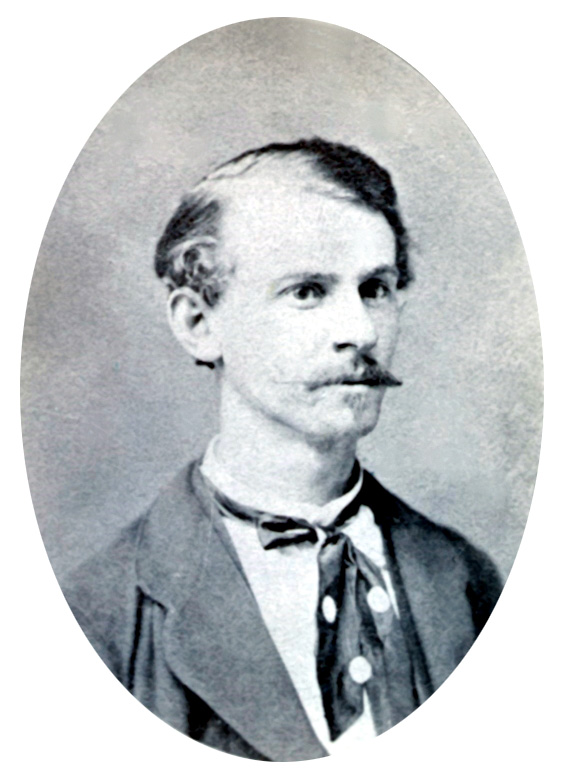

Parsons was born in 1848 and was raised in Texas, serving for a time in the Army of the Confederacy during the American Civil War.

Despite this, he worked as a lawyer to defend ex-slaves’ rights after the war and married Lucy Waller, a woman of mixed-race origins.

Their marriage caused a scandal, and they fled to Chicago and eventually joined the socialist and labor movements.

Lucy Parsons would go on to be a labor leader herself. The Chicago Police Department once claimed that she was “worse than 1,000 rioters.”

Albert Parsons’ actions sparked a national movement, and an estimated 350,000 workers went on strike with the same demand, an eight-hour day.

Parsons spoke at a demonstration in Haymarket Square on May 4th, 1886, partially demonstrating against the Chicago police who had killed four protesters the day before.

A large police presence was at Haymarket that day, and someone threw a bomb toward a group of police officers and killed eight men, including one police officer.

A battle ensued in which many more people were killed or injured. Witnesses pointed to the man they believed threw the bomb, but he was released for unknown reasons.

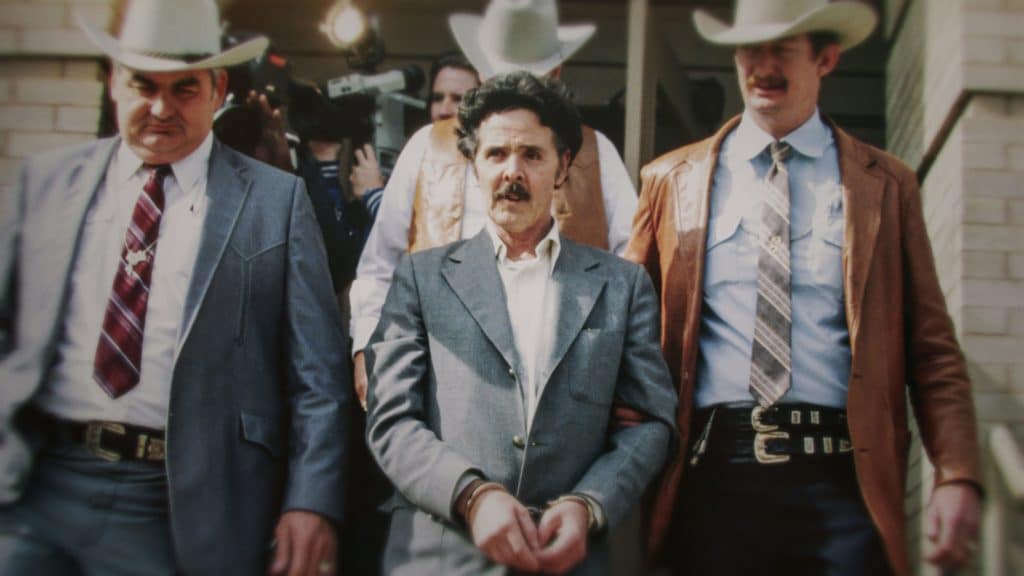

Parsons, suspected of being part of the plot to bomb the police, was wanted and appeared in court of his own free will.

While the prosecution could provide no key evidence linking their suspects to the bomb, they used the labor leaders’ words against them to say that they influenced the bomber to act.

All eight suspects were found guilty, and five were sentenced to hang, including Albert Parsons. He was hanged on November 10th, 1887, a martyr to the cause of the eight-hour work day.

An Invigorated Labor Movement

May 1st, the day of Parsons’ first march in Chicago, became an important anniversary in the labor movement, known as May Day.

Parsons and the others sentenced to death galvanized the labor movement, but they would not be the last casualties of the war.

In Pennsylvania in 1897, newly joined members of the United Mine Workers (UMW) were striking with several demands.

Chief among them was the eight-hour workday. The strikers were almost all immigrants from Eastern Europe.

The strike escalated with altercations between coal miners, striker-breakers, and local authorities.

There were about 10,000 miners on strike, and the mine owners demanded that the Sheriff of Schuylkill County begin arresting them.

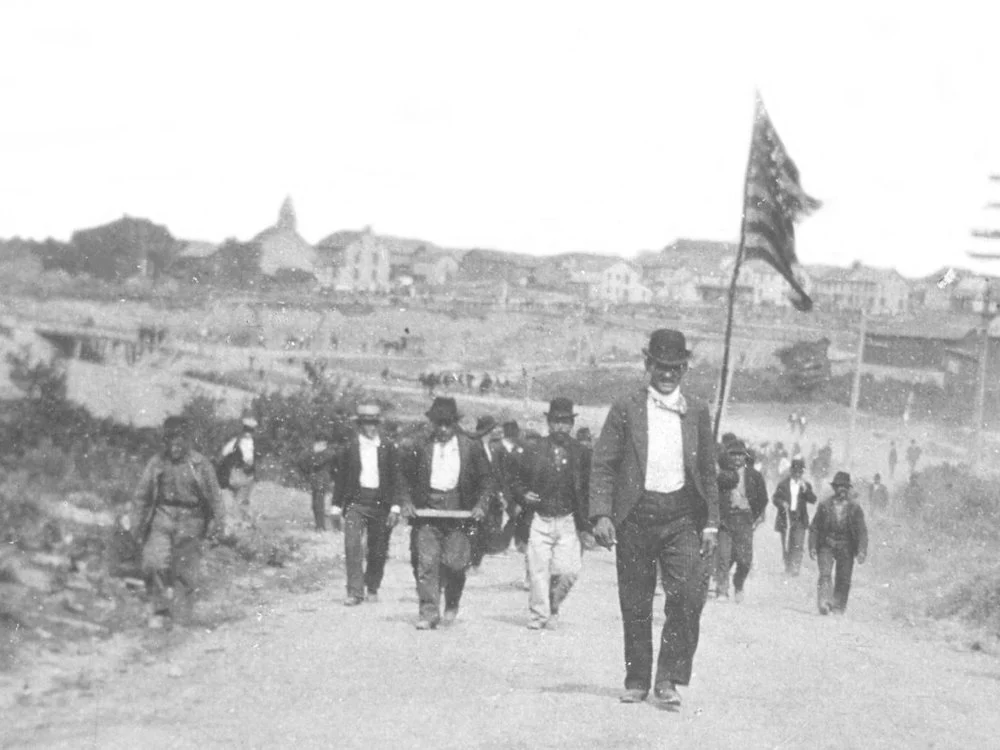

300 to 400 demonstrators marched to Lattimer to support a chapter of the UMW. The sheriff and 150 armed deputies accosted them.

There was a scuffle, and the deputies opened fire, massacring 19 miners and wounding several others.

It would become known as the Lattimer Massacre but was largely forgotten because of the rural location and because the unarmed victims were immigrants.

While the UMW had largely been hesitant to include immigrant miners, especially those of Slavic descent, before the massacre, they eventually changed their tactics.

In calling for a general strike, UMW president John Mitchell stated, “The coal you dig isn’t Slavic or Polish, or Irish coal. It’s just coal.” Using that as a slogan, the 1902 UMW strike eventually achieved an eight-hour workday for all miners.

Teddy Roosevelt Campaigns on a National Eight-Hour Workday

Still, few people were calling for a national requirement for an eight-hour workday.

It would not become widely discussed until the presidential election of 1912 and the surprising reemergence of Teddy Roosevelt.

Roosevelt served as president from 1901 to 1909 but decided not to run for a second full term and instead supported William Howard Taft.

However, after Taft’s performance in his first term, Roosevelt decided to challenge his re-election bid as a third-party candidate. He called his party the Progressive Party.

Part of Roosevelt’s platform in 1912 was forming a Department of Labor and establishing a national eight-hour work day.

Unfortunately, Roosevelt and Taft lost to the Democrat nominee Woodrow Wilson.

While Democrats favored labor reform, Wilson opposed organized labor unions and believed largely in the benefit of competition in the workplace.

However, in 1912, he did, perhaps under pressure, state that he thought workers’ hours should be “rational.”

Nevertheless, the Democratic platform remained vague on any hard and fast rules concerning the regulation of hours.

FDR and The Fair Labor Standards Act

It would take some time, but eventually, the Democrats under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt would complete the journey of an eight-hour workday.

After the devastation of the Great Depression, it was clear that workers needed help and assurance that their desperation for a job would not be used to force them to work excessive hours.

FDR’s Fair Deal put forth the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 through the Department of Labor. This act accomplished a great deal, including creating a division of Wage and Hour in the Department of Labor. This division establishes the national minimum wage.

The Fair Labor Standards Act established a 40-hour work week, which we still hold today.

Any time worked beyond this is considered overtime and must be paid at a higher level, not less than one and a half times normal wages.

Nowhere does the act specify an eight-hour work day or a requirement that a shift begins at 9 am and ends at 5 pm.

Many people work four ten-hour shifts and might work first, second, or third shifts and might work what is sometimes referred to as a “flex schedule,” in which they arrive to work sometime during an agreed period and then leave after their accepted shift is complete.

If they work beyond 40 hours, then they should be paid overtime, but there are exceptions even to that regulation.

Many jobs in the agricultural industry are not subject to all of the rules specified in the Fair Labor Standard Act because they require workers to work long hours during the growing and harvesting seasons, but not necessarily during the winter months.

Fishermen who are out at sea for months are exempt from the overtime rules. Also, salaried jobs, which are often considered at an executive level, are not eligible for overtime under this act.

It is safe to say that most people in America do not work a 9 to 5 job. Often one’s lunch period must be considered, so a person starting at 9 am would take a half-an-hour lunch and so, to fulfill a full eight-hour shift, would not clock out until 5:30 pm.

9 to 5 is a bit of a misnomer

The idea of 9 to 5 being a standard workday comes from the years just after World War II, during a high in the economy when many people worked 9 to 5 with their lunch being counted as part of the workday.

At that time, thanks in large part to the struggle by labor organizers in the previous century, they could enjoy an eight-hour day with plenty of leisure time.

This was the time of the growth of suburbia and the ubiquitous flannel suit. Factory and office work reached a standard schedule, but this did not last for long.

Overtime became more common, and factory workers found their pay stagnated.

As foreign competition and the extended life of the Cold War dragged on, the US economy suffered, and the 9 to 5 became less common.

Today, hours vary greatly, as does the nature of work. As in the country’s early days, the self-employed still set their own hours, but to remain competitive, those hours are often longer than 40 hours a week.

Employers adhere to government regulations where they must, but often create schedules that benefit them more than their employees.

Employees, for their part, are reluctant to organize because companies often deal harshly with any attempts at unionization.

9 to 5 no longer makes much sense in a world of remote, contractual, or work with changing schedules.

Where unions do still exist, employees have the means to address any violations of employment agreements.

Many people in America still enjoy the eight-hour workday thanks to the sacrifices of people like Albert Parsons and the promotion of progressive ideas like those of Theodore Roosevelt and his cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Sources

“The Fair Labor Standards Act Of 1938, As Amended.” US Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/FairLaborStandAct.pdf. Accessed October 28th 2022.

Grubbs, Patrick. “General Trades Union Strike (1835).” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/general-trades-union-strike-1835/. Accessed October 28th 2022.

“1912: Competing Visions for America | eHISTORY.” eHISTORY, https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/1912/default. Accessed October 28th 2022.

“Parsons Biography.” Anarchy Archives, http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/bright/aparsons/bio.html. Accessed October 28th 2022.

Shackel, Paul A. “How a 1897 Massacre of Pennsylvania Coal Miners Morphed From a Galvanizing Crisis to Forgotten History.” Smithsonian Magazine, March 13th 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-1897-massacre-pennsylvania-coal-miners-morphed-galvanizing-crisis-forgotten-history-180971695/. Accessed October 28th 2022.