Part myth, part legend, the African warrior-chief known as Shaka Zulu transformed the Zulu people. This was a relatively small and insignificant tribe. And he turned them into one of the most savage and well-trained war machines in African history.

To some, Shaka was a nation-builder. He was a uniter of Black people. A bringer of peace. A bringer of law and order. A prophet. A philosopher. Even a visionary.

But to others, he was nothing more than a despot. A tyrant. A dictator. A destroyer. A murderer. A savage. And a barbarian.

Historians have compared him to Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Attila the Hun, and Napoleon. But hyperbole aside, who was Shaka Zulu?

Born into Shame and Prestige

Shaka Zulu (actual name, Sigidi kaSenzangakhona) was born around 1787. He was born in an area of southeast Africa between the Drakensberg mountains and the Indian Ocean. He was born to Senzangakhona, chieftain of the amaZulu (Nkosinkulu) people, and Nandi, a princess of the neighboring Langeni clan.

Because their families were related by clan, their marriage violated the Zulu familial taboo. The stigma even extended to the child of their union. Despite the inappropriateness of their relationship, Senzangakona claimed “Shaka” and installed Nandi as his third wife. This went against the wishes of primary wives one and two.

Accordingly, Shaka spent his early years at his father’s kraal (village) near present-day Babanango. This was in the sacred locality known as the EmaKhosini or “Burial-place of the Kings,” where Senzangakhona’s forebears had been Zulu chiefs for generations.

When Shaka was six, however, tensions within the tribe concerning Shaka’s eventual ascendancy as an illegitimate king forced his father to banish mother and son.

Outcasts

Nandi had no choice but to return to her clan with her son, but she was met with rejection. Being expelled by Senzangakhona effectively made Shaka a fatherless bastard and Nandi an isifebe (whore). Thus, she was considered unclean and essentially unmarriable by any man of status. Subsequently, around 1802, she and her son were again sent into exile.

After wandering the African countryside for several years, Nandi was taken in by the Dletsheni. This was a sub-clan of the powerful Mthethwa Empire of the KwaZulu-Natal. This was part of a newly-formed Southern African state that arose in the 18th century south of Delagoa Bay and inland in the Nkandla region of South Africa.

But despite finding a home with the Dletsheni, Shaka carried the stigma of a fatherless orphan. He remained an outsider among the other boys of the clan. Furthermore, he was tall and gangly and didn’t physically look like the other boys. Moreover, they resented his repeated claims of royal descent.

Manhood and Military Service

When Shaka was 23, Dingiswayo, the Mthethwa Empire’s primary chieftain, called up Shaka’s Dletsheni age group for military service, as was customary. Shaka was now exceptionally tall and powerfully built. He stood out both for his intimidating size and the military prowess he immediately exhibited.

He found satisfaction he’d never known in his life. He was part of the iziCwe regiment and he had the comradery of other young men that he previously lacked. The battlefield also provided an arena in which he could demonstrate his natural talents for combat and leadership.

Shaka’s natural aptitude for military life soon drew the attention of his commander, Dingiswayo. He rewarded his burgeoning abilities with frequent advancement. He was fascinated with battlefield strategy and tactics like no other young man under his command.

Dingiswayo began to instruct Shaka on the finer points of war. He gave him the moniker Nodumehlezi (“The one who when seated causes the earth to rumble”). Shaka quickly became one of the foremost commanders in Dingiswayo’s army.

Revamping Zulu Armaments

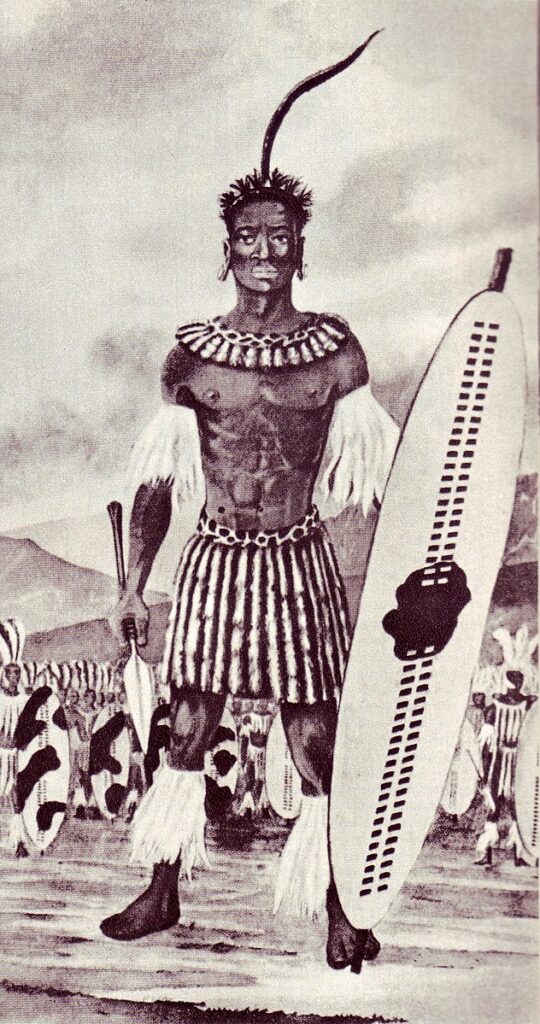

Shaka’s first act as an induna (commander) was to upgrade his men’s armaments. Like all Zulu regiments at this time, his men were armed with standard ox-hide shields and lightweight throwing spears.

This type of shoddy weaponry was of little consequence to the Zulu War Machine. This was because battles were typically little more than brief, bloodless skirmishes in which the outnumbered side would surrender before any casualties occurred.

But under Shaka’s command, battles were a prelude to conquest and all-out war. Accordingly, Shaka rearmed his men with well-crafted ikiwa. There were long-bladed, short-hafted stabbing weapons designed to be used up close and not thrown from a distance (like a hunting spear).

Additionally, their shields were to be used as bludgeoning weapons, as much as defenses. And to toughen his men for the battlefield, Shaka prohibited the wearing of sandals, making them run barefoot over the rough thorny ground to condition their feet and make them more nimble.

Revolutionary Warfare Tactics

After vastly improving Zulu armaments, Shaka demonstrated his genius for battlefield strategy. He not only improved on centuries-old tactics but developed new ones never before applied in African warfare.

Shaka instituted a regimental system based on age groups, quartered at separate kraals (ten to twenty miles apart). They were distinguished from one another by uniform markings on shields, headdresses, and ornamentation for identity and to promote fraternity.

Shaka then divided each regiment (known collectively as impi) into four tactical groups that functioned in tandem: The first, designated the “chest,” closed in on the enemy to pin them down. The second and third, the “two horns,” raced out to encircle and attack from behind.

The fourth, a reserve unit known as the “loins,” waited nearby. They were reportedly instructed to face away from the battle so as not to become overly anxious. They could be sent in to reinforce any part of the trap the enemy threatened to breach.

Shaka: Chief of the amaZulu

In 1816, Shaka’s father, Senzangakona, died. This made Shaka’s younger half-brother Sigujana heir to the Zulu throne. His reign was to be short-lived.

Dingiswayo (the Mthethwa Empire’s primary chieftain and Shaka’s mentor) assigned a regiment of elite warriors to Shaka’s command so that he might seize control of the chiefdom. He wanted Sigujana put to death.

From the moment Shaka crowned himself Chief of the Zulu, he faced very little resistance. Although, he technically remained a vassal of the larger, Mthethwa Paramountcy.

Chief Dingiswayo died in battle a year later at the hands of rival chief Zwide, leader of the Ndwandwe Nation. Shaka took over as chief of the Mthethwa Paramountcy. He reformed the defeated Mthethwa forces (and many other regional tribes).

He also subsequently defeated Zwide in the Zulu Civil War of 1819–20, thus sealing his absolute control of the amaZulu. Henceforth began the Shaka Zulu legend.

Expansion into South Africa

As Shaka became more respected and feared by the Zulu people, they became more receptive to his militant point of view. He established himself as an unstoppable warrior.

And he convinced the Zulu that the most effective way to become more powerful as a tribe was by conquering, subduing, and exterminating (when necessary) other tribes. His aggressive ideas greatly influenced the sociological outlook of the Zulu, who soon supported his plan for conquest.

In fast succession, the Zulu, under Chief Shaka, decimated one small clan after another. They incorporated the survivors into the Zulu.

It’s said that whenever possible, he wanted to punish any of his boyhood tormentors. He singled them out and impaled them on the stakes of their kraal fences. In less than a year, the Zulu quadrupled in number, assimilating as many as 100 neighboring chiefdoms.

Even so, Shaka also sought personal gratification only derived from worship, subservience, and tribute. He welcomed alliances that benefited him and cost him nothing.

This was exemplified by his alliances with Chief Zihlandlo of the Mkhize, Chief Jobe of the Sithole, and Chief Mathubane of the Thuli. These were leaders who voluntarily placed their armies under Shaka’s command. They were typically made captains and allowed to serve as Shaka’s advisors.

Decisive Battles: The Ndwandwe Empire

Shaka’s first battle of consequence was the “Battle of Gqokli Hill.” It took place on the Mfolozi River in April of 1818. He fought against Chief Zwide of the Ndwandwe who was the powerful leader who killed Shaka’s mentor, chief Dingiswayo of the Mthethwa Empire.

This was the first battle in which Shaka had the opportunity to fully demonstrate the effectiveness of the armament and tactical innovations he’d instituted in his ever-expanding army.

Proving his ability to analyze a battlefield, Shaka chose an easily defensible position on the crest of Gqokli Hill. After resisting several frontal assaults by Ndwandwe warriors, Shaka feigned retreat. He then signaled his reserve forces to circle the hill and attack the enemy’s rear—which proved decisively effective.

Though casualties were heavy on both sides, Shaka had proven his brilliance for battle. When the battle concluded, however, Shaka discovered that Chief Zwide had escaped.

Shaka’s second major battle took place two years later on the Mhlatuze River. Here, he again faced the Ndwandwen army (this time under the command of one of Chief Zwide’s generals).

Following a two-day marathon battle during which the Zulu essentially decimated the enemy, Shaka then led a fresh reserve of warriors some 70 miles (110 kilometers) to Chief Zwide’s royal kraal and burned it to the ground.

Again, Zwide managed to escape. This time, he took refuge with a female chieftainess named Mjanji, ruler of a beBelu clan (which bordered the Mthethwa Empire). A short time later, Chief Zwide died in what historians consider mysterious circumstances.

From that time forward, Shaka’s power was absolute.

The British and Cape Town, South Africa

By 1815, the “Cape Colony” (today, Cape Town, South Africa) officially became a British possession. The British government was actively encouraging settlement here.

Particularly in what remained a disputed area between the established colony and the Xhosa people in what is now the Eastern Cape. This period of colonization coincided with the rise in power of King Shaka. The amaZulu occupied a large swath of land to the northeast.

Though Shaka was fully aware of the Whites settling the coastal area, he was less concerned about their presence than they were of his. The British grew increasingly concerned that the Zulu would one day go on a killing rampage. Shaka was rumored to have some 500,000 warriors at his disposal.

To establish peace for the residents of Cape Colony, in 1824 government representatives sponsored a delegation. This included Nathaniel Isaacs and Dr. Henry Francis Fynn who represented the Farewell Trading Company. They sailed to Port Natal (present-day Durban) to meet with Shaka and gain permission to establish a post.

Before this, Shaka had granted permission to some Europeans to enter Zulu territory on a few rare occasions. And as Port Natal was over 100 miles from Shaka’s headquarters, he held very little concern about their presence.

Shortly after arrival, Henry Francis Fynn, both physician and traveling partner of Nathaniel Isaacs, had the opportunity to treat King Shaka after an assassination attempt by a rival tribe member. To show his gratitude, Shaka granted Fynn and Isaacs permission to operate within the Zulu kingdom.

This interaction allowed Shaka to observe European knowledge and technology in action. But he continued to believe the Zulu were superior.

The Death of Nandi, Shaka’s Mother

In October of 1827, while on a hunting trip accompanied by Henry Francis Fynn, Shaka received news that his mother, Nandi, was gravely ill.

By noon the following day, he and Fynn had walked to her royal kraal. Shaka asked the doctor to attend to Nandi. He essentially demanded that Fynn save her life.

In his journal, Fynn describes Nandi’s hut as being filled with mourning women and smoke, forcing him to ventilate the hut to be able to breathe. Nandi was already in a coma and Fynn told Shaka that he did not expect her to live through the day.

A short time later, Shaka was given the bad news that Nandi had died. Fynn attributed her death to dysentery. But persistent Zulu oral history insists Shaka killed her.

During his period of mourning, the grief-stricken Shaka ordered that no crops should be planted during the following year, no milk (the basis of the Zulu diet) was to be consumed, and any woman who became pregnant was to be killed–along with her husband.

According to legend, at least 7000 people deemed insufficiently bereaved were executed. Cows were also slaughtered so their calves would know how it felt to lose their mother.

Shaka’s erratic behavior drew anger and disquietude from his captains. As well as the thousands of followers across amaZulu, which made enemies of his closest advisors.

The Assassination of Shaka Zulu

In 1828, Shaka’s half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, made at least two attempts to assassinate Shaka. In September of that year, Shaka (or perhaps his captains) sent all available Zulu to raid tribes to the north. This left the royal kraal critically short of security.

They used this opportunity to their advantage. Shaka’s half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, his personal bodyguard Mbopha, and a group of their compatriots entered Shaka’s royal hut and murdered him.

Shaka’s corpse is said to have been dumped into an empty grain pit and filled with stones and mud. Its location is still unknown.

Aftermath

Having died without a designated heir, Shaka’s half-brother Dingane assumed power. And with British support, he took over Zulu leadership in 1840 and ruled for some 12 years.

Henry Francis Fynn and Nathaniel Isaacs became fluent Zulu linguists (and Shaka confidants). Most of what is known today of Zulu/Shaka history stems from their writings.

Late in the 19th century, the Zulu would be one of the few African tribes to defeat the British Army at the Battle of Isandlwana.

References

South African History Online, “Shaka Zulu,” Shaka Zulu | South African History Online (sahistory.org.za)

Britannica, “Shaka Zulu,” Shaka | Zulu chief | Britannica

Wright, John, “RECONSTITUTING SHAKA ZULU FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: PART ONE,” https://phambo.wiser.org.za/files/seminars/Wright2004.pdf

Geni.com., “Shaka Zulu,” https://www.geni.com/projects/Shaka-Zulu/8876

SAHistory.org., “Shaka Zulu,” https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/shaka-zulu