Last updated on October 15th, 2023 at 06:48 pm

Before the pharaohs, before the gods, there was the scarab.

The significance of the scarab beetle in Egypt dates back over eight thousand years. Mummified scarabs and scarab-shaped amulets have been found in tombs dating back to the beginning of the Predynastic period. It came to be the face of one of their most important gods.

To the ancient Egyptians, this sacred beetle symbolized everlasting life.

The Scarab Beetle

The Scarabaeidae family is made up of over thirty thousand species of beetles located on every continent except for Antarctica. The smallest members of this family could stand on the tip of your pinky finger, and the largest are over six inches long.

The scarab beetle of greatest significance to ancient Egyptians was Scarabaeus sacer, the sacred scarab. It’s also commonly referred to as the Egyptian scarab.

You probably know it by a different name: dung beetle.

Like other dung beetles, these scarabs create great balls of dung many times larger than their own bodies. They deposit these balls underground, where they may lay an egg in the midst of this plenty or feast upon it themselves. Larvae grow and pupate in these balls of dung before emerging fully formed.

Scarabs in Ancient Egypt

To ancient Egyptians, the scarab symbolized life and renewal.

Where we have eggs and chicks and bunnies to represent life and birth and springtime, they had… dung beetles. A more apt comparison might be our cultural obsession with the metamorphosis of butterflies.

Because these young beetles emerge from balls of dung, Egyptians believed that scarabs emerged fully formed from the soil, godlike in their ability to create themselves.

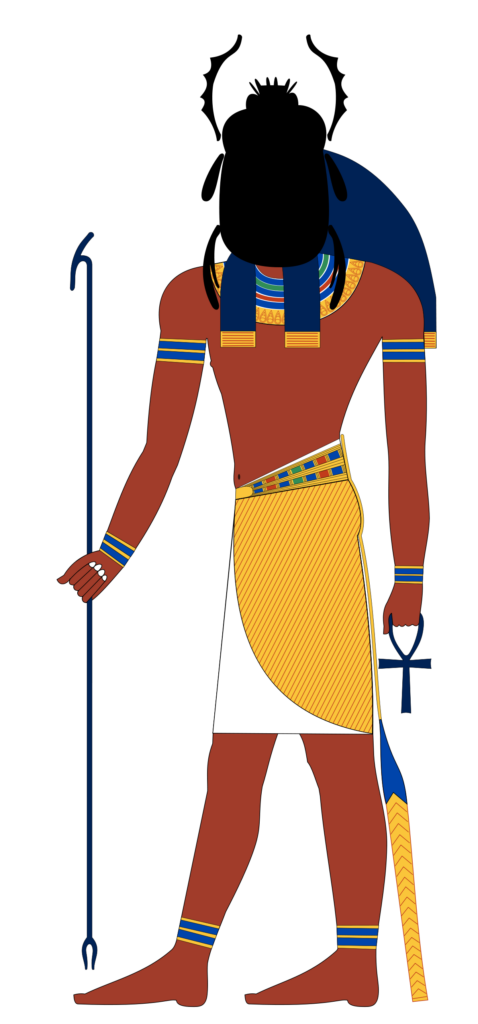

Khepri the Sun God

Khepri was a scarab-headed god tasked with rolling the sun across the sky. His official title was He Who Is Coming Into Being.

Unlike most of the thousands of gods throughout Egyptian history, Khepri created himself out of nothingness, just as Egyptians thought that dung beetles did.

According to some interpretations, he was a minor sun deity who was subordinate to the sun god Ra. In other interpretations, Khepri was one aspect of Ra: that of the morning sun.

Each night, ancient Egyptians believed, the sun died and traveled across the underworld.

Each morning, the sun was born anew.

It was believed that the sun god Khepri took the form of a scarab beetle each morning before daybreak. In this form, he would roll the sun across the sky and bring light to the world.

The Egyptian word for the scarab beetle was hprr, which also meant ‘rising from’ or ‘come into being itself’ – a reference to the apparently spontaneous birth of these beetles. It’s related to the word hpr, which means ‘to become’ or ‘to change’.

The word hprr evolved into hpri, and the scarab gave its name to the sun god Khepri.

This scarab god symbolized creation, light, protection, and resurrection.

Scarabs in Egyptian Art

Scarabs were often depicted in jewelry, seals, paintings, and more.

They were common not just among the elite, but also in the homes of ordinary Egyptians. Commoners wore small amulets carved out of soft stones, and the wealthy had amulets made from precious gems and set in gold.

Amulets in the shape of scarabs were commonly believed to have regenerative properties. They were valued both as amulets to be worn in everyday life and as powerful items worth bringing along to the afterlife.

These scarabs were often inscribed with messages and designs on the bottom. Many were engraved with images of deities, religious symbols, and other sacred animals. Others were inscribed with names, good wishes, or deeply held beliefs. There are even commemorative scarabs that tell of major historical events.

With or without inscriptions, these carved beetles were sacred objects.

Like the scarab beetles that inspired them, these pieces of Egyptian art traveled far beyond the kingdom of Egypt even in ancient times. They’ve been found in Palestine, Spain, Italy, and Greece.

Everyday Use

Even ancient Egyptians of modest means wore scarab amulets on leather cords around their necks. They were also commonly worn as bracelets. In Middle Kingdom Egypt, they became common as rings as well.

Most scarab pendants were quite small, often just one centimeter long.

Most were carved from steatite, a soft and easily carved rock also known as soapstone. Despite how easy this stone is to carve, it’s very durable. The carved stone was often coated in colored glaze to turn them blue or green.

They were also carved out of basalt, jasper, turquoise, malachite, serpentine, lapis lazuli, and alabaster. Archeologists have also found scarabs constructed from pottery and colored glass.

Scarabs with inscribed bottoms were often used as seals, which were vitally important to Egyptian culture. In a time and place with no locks or keys, confidential documents were often encased in clay and stamped with a seal, to be opened by the recipient.

Scarabs in the Afterlife

In addition to wearing them in this life, ancient Egyptians counted on their sacred scarabs to see them on to the next. Scarab amulets were sewn onto mummy wrappings to ward off evil on the journey to the next world.

Some tombs included large scarabs, longer than seven centimeters. These large amulets were most often placed upon the chests of mummies, and many were inscribed with verses from sacred texts.

Often called heart scarabs, these large engraved carvings were inscribed with a prayer.

In Egyptian lore, each person had to pass through the ceremony in which the jackal god Anubis would weigh their heart against a feather. If their heart was the lighter of the two, they would be allowed to pass on to the next world.

If not, they would cease to exist.

The prayer inscribed upon heart scarabs implored their own heart not to bear witness against them, lest they be devoured by a monstrous hippopotamus and disappear forever.

They carried scarabs with them all through this life and on into the next, where they would be reborn just as Khepri was each day at dawn.