Hara-kiri translates to “belly cutting” or “stomach cutting.” As the name implies, it involves slicing your stomach with a knife. It’s a horrific, agonizing way to go. So why would anybody willingly do it to themselves?

The answer concerns the strict samurai code of conduct, which placed honor above all else. For a samurai, death was preferable to dishonor, and hara-kiri was a way to avoid a dishonorable fate.

Over time, this ritualized suicide became a kind of art form, a formal ceremony that converted a bloody and horrifying act into something people regarded as beautiful – at least in the retellings.

In this article, we’ll discuss the origins of hara-kiri, why it was so important, and what it means today. But before diving into the history of hara-kiri, let’s look at the ritual itself.

Seppuku and Hara-Kiri: Samurai Stomach Cutting

Hara-kiri is the name that most Westerners are familiar with, while seppuku is more common in Japan. But no matter which term you use, they both refer to the same thing: a formal act of self-disembowelment.

Seppuku involved several steps that began with the samurai being told where and when he would be committing the act. During the ceremony, the samurai would be accompanied by a kaishakunin, essentially an assistant and witness.

The kaishakunin’s job was to cut off the samurai’s head at the right moment and ensure everything went smoothly. To be chosen as a kaishakunin was a great honor and one not to be taken lightly.

Typically, only people with excellent swordsmanship were chosen as kaishakunin. And you’ll soon see why.

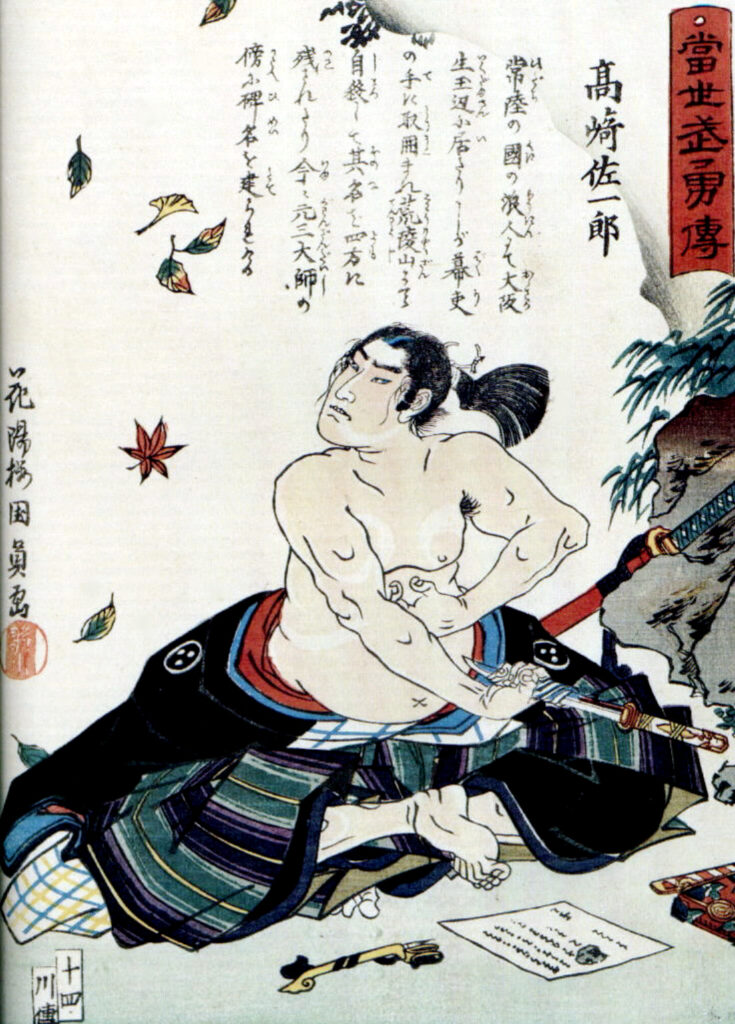

To begin the ceremony, the samurai would first greet the kaishakunin. After the greeting, he would kneel atop a series of tatami mats. Often, there would be red rugs to conceal his blood.

Once kneeling, the knife would be brought forward and placed on a tray roughly three feet before him. He would then bow to the witnesses and carefully open his kimono to expose the bare flesh of his abdomen.

There is really no one set way of performing the stomach cutting, but generally, the samurai would then grasp the knife and plunge it into his left side, slicing across to the right just above the navel. The first cut would sometimes be followed by an upward or downward slice, after which he would remove the blade.

While the samurai sliced into his stomach, the kaishakunin would be crouched by his left side, just out of sight. At a given moment, the kaishakunin would then come forward and perform the decapitation.

Ideally, he’d be able to cut the samurai’s head off in one stroke; sometimes, it would take two or more tries. Sometimes, a kaishakunin would have to resort to sawing the head off. This is why it was best to choose a kaishakunin with excellent swordsmanship.

Once a clean cut was made, the kaishakunin or his assistant would pick up the head and show it to the witnesses before placing it into a basket.

In 1868, a Japanese man named Taki Zenaburo was instructed to commit seppuku as punishment for ordering his troops to fire on foreign diplomats.

The following excerpt comes from an American’s description of Zenzaburo’s death:

Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound gave slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leant forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku , who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash – a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body. A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man.

As you can see, seppuku was a solemn ceremony that turned death into a spectacle. Everyone present had a role to play, and the one committing seppuku was always the protagonist.

But seppuku didn’t start out as such a formal event.

The Origins of Seppuku

In Japan, warriors committing suicide on battlefields date back much longer than seppuku itself.

Before stomach cutting became a ritual, warriors used a variety of means to commit suicide, including submerging themselves in water with their armor on or flinging themselves from their horse with a knife in their mouth.

Seppuku begins to appear in fictionalized accounts of battles beginning in the 12th century. In its earliest form, seppuku typically occurred when a warrior was surrounded by his enemy and had no hope of winning the battle.

Seppuku gave the warrior one last chance to show his manliness and courage in those instances. Rather than be taken alive, he would slash his stomach open, often in full view of his enemies.

There are countless tales of doomed samurai committing suicide in grisly ways. In The Tale of Yoshitsune, which describes an incident from November 3, 1186, a warrior named Sato Tadanobu surrounds himself and decides to take his own life.

Before slashing his belly open, he says, “Now you’ll see a tough man cut his belly! I’ll kill myself before any of you can take my head, and my death will be a model for all who come after me.”

After reciting a few Buddhist verses, he cuts his belly, flings his intestines onto the ground, and throws himself onto his sword. His enemies are awestruck by his demonstration of courage, and they treat him like a hero. In one painful act, Tadanobu becomes immortalized.

These battlefield suicides were an important part of early samurai culture. It was a way for warriors to avoid being captured, which often meant being tortured or subjected to cruel methods of execution, such as crucifixion.

But the impromptu stomach cutting that appears in medieval literature was a far cry from the institutionalized seppuku that came later. It wasn’t until the early 17h century, during Japan’s unification, that seppuku became a formalized part of samurai culture.

Bushido: The Samurai Code of Conduct

Bushido means, “the way of the warrior,” and was a code of conduct developed by Japanese leaders during the Tokugawa shogunate. It was meant to instill loyalty in the samurai, to channel their extreme machismo and fearlessness into something more suitable for peacetime. Seppuku became an important part of this code of conduct, as it epitomized a samurai’s stoic attitude toward death.

It also helped establish the idea that samurai are distinct from ordinary people. It was thought that an ordinary person could never face death in the same unflinching way that a samurai could.

For the samurai themselves, seppuku was a privilege. It was a way to make up for a shameful error or to demonstrate loyalty. As a result, there are many accounts of samurai killing themselves upon the death of their lord or even to make a point that could not be made otherwise.

Honor was so important to the samurai that it often took precedence over one’s life. According to a list of punishments dating from the 1590s, seppuku was considered a less severe punishment than losing one’s samurai status.

In at least one case, a samurai’s family intervened on his behalf, arguing that his punishment should be reduced from stripping his status to seppuku. For them, suicide was more lenient than having to suffer dishonor.

The use of seppuku extended beyond the samurai themselves. Women were sometimes known to commit seppuku along with their husbands.

They also performed jigai, a method in which they slit their throats rather than cut their stomachs. In both cases, women would typically tie their knees together in order to avoid immodesty.

When children committed seppuku, it was often forced on them as punishment for something their father had done. They would often be given a paper fan instead of a dagger and were told that they would merely be practicing for the real thing.

At the moment that the child dragged the paper fan across their stomach, the kaishakunin would take out a real sword and strike their head off.

Is Seppuku Still Practiced?

Seppuku was banned in 1873, but the practice didn’t completely disappear. During World War II, Japanese soldiers were instructed to fight to the death rather than allow themselves to be captured. As a result, some soldiers decided to end their lives by committing seppuku.

At the end of the war, many officers did the same. Vice admiral Takijiro Onishi, the inventor of suicide plane strikes known as kamikaze, committed seppuku upon hearing the news of the Emperor’s surrender. He had been responsible for sending thousands of young men to their deaths in his desperate attempt to save Japan from defeat.

For Onishi, seppuku was a way to atone for his actions. The night before he killed himself, he wrote a letter expressing remorse for his failures and sending so many young men to die. He chose to commit seppuku without using a kaishakunin, opting instead to suffer a slow, agonizing death that lasted 15 hours.

One of the most famous public incidents involving seppuku occurred in 1970, when Yukio Mishima, a famous Japanese novelist known for his nationalism and machismo, carried out a failed coup attempt. He kidnapped the commander of an army base, ordered him to assemble the garrison men, and then addressed the crowd. He had hoped to stir up support for his coup.

Instead, about a thousand servicemen listened unsympathetically as Mishima pleaded with them to rise up. Finally, seeing his speech’s little effect, Mishima decided to take his own life.

Withdrawing to the room where the general was tied up, Mishima took out a knife, knelt down on a red carpet, and ripped open his belly.

Unfortunately for Mishima, things didn’t go as planned. One of the students was supposed to act as kaishakunin, but he didn’t react in time. Mishima fell forward onto the carpet while the student swung clumsily at his neck. As Mishima writhed around on the floor, another student finally had to step forward and finish the job.

Yukio Mishima’s brutal death shocked the world because it seemed so out of place in the post-World War Two era. But it was not the last time someone would commit seppuku.

Although it is extremely rare, every once and a while, someone will still choose to end their life by way of this ancient practice.

Honor and Suicide in Modern Japan

The samurai code of conduct may not exist anymore, but honor still contributes to Japan’s high suicide rate. Duty and obligation form a central part of Japanese society.

When someone is unable to fulfill what is expected of them, shame often results. Whether it’s the loss of a job or the failure to support their family in some way, that burden of shame can drive a person to suicide.

And the pressure to commit suicide increases if they know they can collect money from a life insurance policy. This is particularly true for the elderly, who sometimes see suicide as a way to contribute to their family.

Seppuku may be an ancient practice, but its history remains.

Sources

https://www.thecollector.com/hara-kiri-the-samurai-ritual-of-seppuku/

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/1999/03/why-do-japanese-commit-hara-kiri.html

http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=069

https://www.pbs.org/mosthonorableson/shame.html

Morton, Robert. A. B. Mitford and the Birth of Japan As a Modern State : Letters Home, Amsterdam University Press, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/universidadcomplutense-ebooks/detail.action?docID=6359735.

Rankin, Andrew. Seppuku: A History of Samurai Suicide. Kodansha USA, 2018.

https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/seppuku-ritual-despedida-samurai_11256

Scott-Stokes, Henry. The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Tuttle, 2003.