Evaluating generalship is often a practice of choosing arbitrary values to rank. Military historians will argue infinitely over the relative merits of one leader over another. Ranking Roman generals is not immune to this kind of controversy.

Sun Tzu provides us with some guidance: “Therefore the skillful leader subdues the enemy’s troops without any fighting; he captures their cities without laying siege to them; he overthrows their kingdom without lengthy operations in the field.”

We can break down this aphorism into three parts to analyze Roman generals (although they did not know who Sun Tzu was, his advice is evergreen). Each of the generals on this list applied these principles differently. However, the outcomes were ones of success (or learning from earlier failures).

Rome was often operating at a military disadvantage. From the beginning, it was a small city-state that grew by forging alliances with its neighbors.

Even as a mighty empire, its far-flung borders placed leaders at the edge of their logistical and manpower constraints. It was within these constraints that generals either rose or fell in the face of foes that often vastly outnumbered their forces.

During its time, the Roman Legion was an unparalleled fighting force whose discipline and organization could overcome any enemy that presented itself. However, even the vaunted legions, if poorly led, could fall.

For every general on this list, there are many Aemilius Pauluses, who allowed his forces to be wiped out by an inferior force of Carthaginians at Cannae.

If there is one characteristic that the generals on this list share, it’s that they were efficient commanders. They followed Sun Tzu’s guidance, husbanded their forces, only gave battle under favorable circumstances, and grew Rome’s power in the face of many enemies.

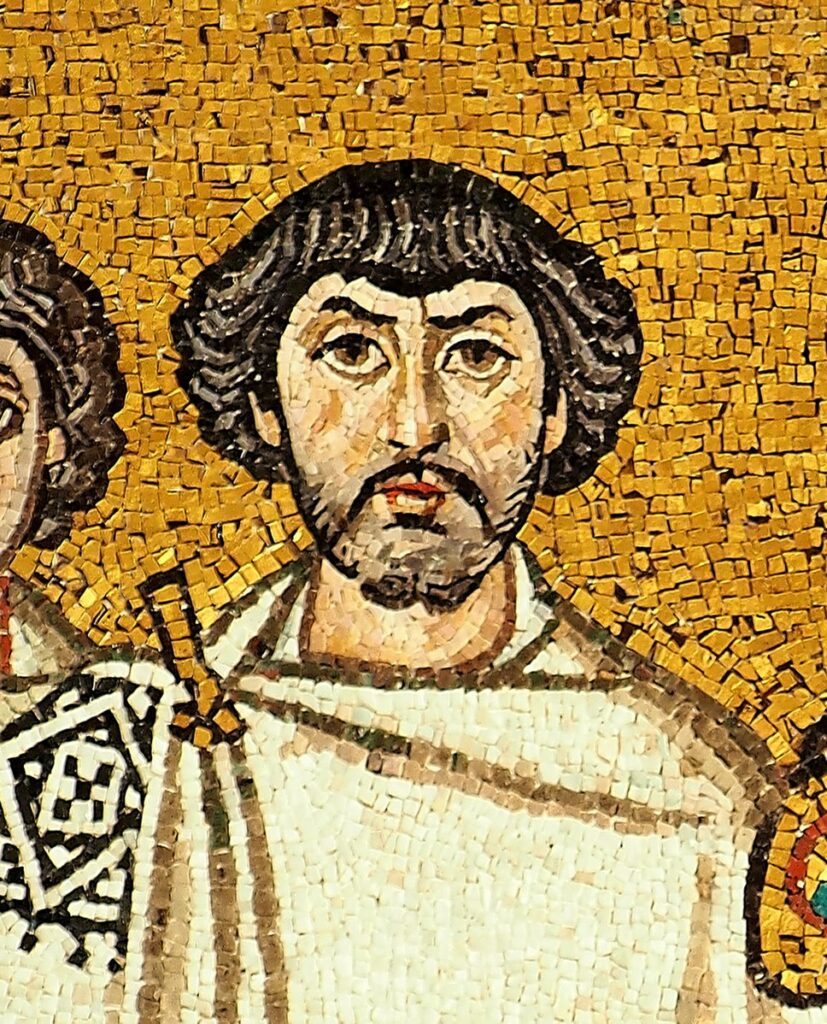

10) Belisarius

Belisarius served the Eastern Emperor Justin I and his successor Justinian. He lived in the first half of the 6th century BCE, a half-century after the Goths sacked Rome. He is considered by many historians to have been a Roman general in the mold of the others on this list.

Belisarius, originally from what is now Bulgaria, started his military career as part of Justinian’s bodyguard. However, when the Byzantine Empire went to war with the Persian Sassanid Empire in 526, he was sent to command part of the army there.

This began a decade of military excellence that would see Belisarius expand Byzantine power into areas formerly ruled by the “old” Rome, including Rome itself.

Belisarius exemplified Sun Tzu’s ideal for achieving victory without excessive violence or lengthy operations. In North Africa, he used a small reconnaissance force and diplomacy to secure the surrender of Vandal-held cities. He then launched a surprise attack on the Vandal capital of Carthage, which fell without a lengthy siege.

In Italy, Belisarius recognized that a frontal assault on the Gothic capital of Ravenna would be costly and instead secured key strategic locations to weaken the Gothic kingdom’s hold. He then used swift cavalry raids to capture Gothic-held cities.

Belisarius achieved success through strategic thinking, superior tactics, and diplomatic measures, which align with Sun Tzu’s philosophy of achieving victory without resorting to brute force.

9) Germanicus Julius Caesar

Germanicus was born to a noble family in 15 BCE. He was made a praetor at a young age and sent to command forces along the Rhine River in Germany by Emperor Tiberius.

When he arrived, several of his legions were in open revolt because of the harsh conditions on the frontier in the wake of the significant Roman defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Germanicus paid off the legions with his own money, restoring order, and winning the loyalty of his troops.

His base secured, he set about marching into the difficult German terrain in search of the chieftain, who slaughtered three Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest. He raided Germanic villages and forced the Germans to respond.

Germanicus subdued the enemy‘s troops without fighting by using a combination of diplomacy and military strategy. He won the loyalty of some Germanic tribes by offering them incentives and convincing them to join his forces.

By doing so, he weakened the unity of his enemies and reduced the strength of their armies.

8) Titus Flavius Vaspasianus (Vespasian)

Born into a common family in 9 CE, Vespasian was an ambitious climber in Roman politics. However, his early career as a civil servant was rather unremarkable.

His connections with the imperial court offered him a way out as a commander of a Roman legion stationed in Germania in 41 CE. Over the coming decades, he would command forces invading Britain. He ultimately achieved a commanding position in the near east by defeating the Jewish revolt, putting himself in a position to become emperor in 69 CE.

One way Vespasian subdued his enemies without fighting was by using diplomacy and political maneuvering.

For example, the emperor appointed Vespasian to lead the Roman legions in Judea. He quickly realized that the Jewish rebels were well-fortified and prepared for a long siege. Instead of engaging in a prolonged and costly battle, Vespasian cut off the rebels’ supply lines, starving them into submission.

He also made strategic alliances with Jewish leaders who opposed the rebellion, which weakened the rebels’ support base and eventually led to their defeat.

In 69 CE, his forces took part in the Year of Four Emperors. After inconclusive fighting that destroyed large portions of the capital, Vespasian dispatched food from Egypt, resulting in his election to Emperor by the Senate later that year. This again showed his strategic acumen by letting his opponents fight and appearing as the party of peace.

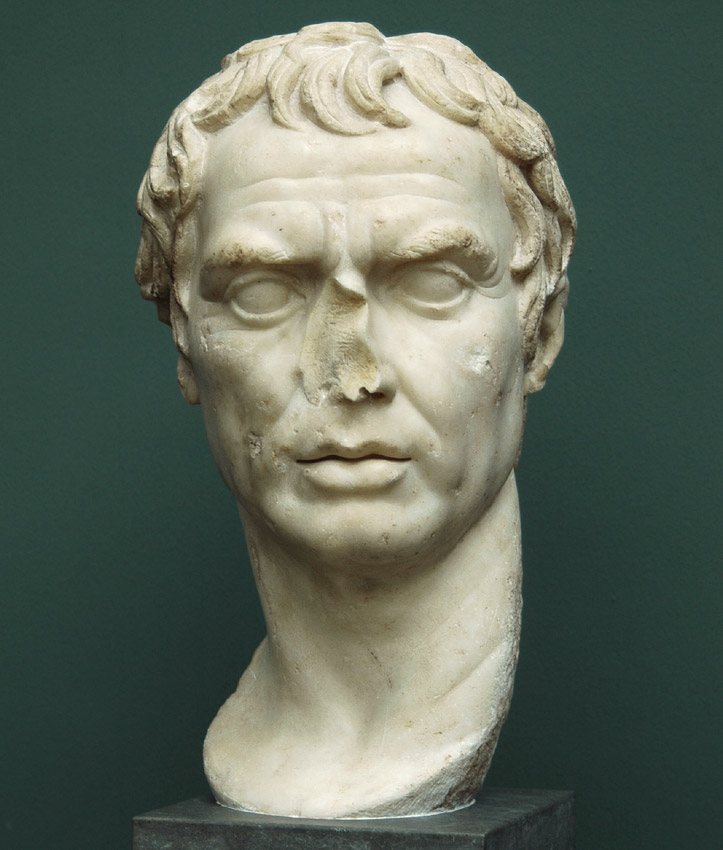

7) Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Sulla was born to an impoverished Roman noble family in 138 BCE. Like Vespasian, he had to claw his way up the hierarchy, becoming a quaestor at 30.

The Senate assigned him to serve under the Consul Gaius Marius in the Province of Numidia, which had been at war with Rome for four years by this point.

Between 108 and 80 BCE, he achieved a series of victories stretching from Africa to the near east to the gates of Rome itself that would establish him at the pinnacle of the Roman Republic until his retirement in 78 BCE.

Sulla’s success in overthrowing the Kingdom of Pontus was equally impressive. He achieved his objectives without lengthy operations in the field by employing a combination of military force and political maneuvering. He defeated Mithridates’ army in several battles and then entered negotiations with the king.

Sulla secured a peace treaty that allowed him to withdraw his troops without further fighting. He also forced Mithridates to pay a large indemnity to Rome.

Sulla’s ability to subdue his enemies without excessive bloodshed was because of his keen understanding of psychology and his ability to manipulate his opponents. He exploited the weaknesses of his enemies. He played on their fears and desires to achieve his means.

He was also a master of propaganda, using his victories to enhance his reputation and undermine that of his enemies.

6) Fabius Maximus

Fabius Maximus was born in Rome around 280 BCE as a member of a patrician family. He was consul of the Republic five times.

He is best known for his generalship during the Punic Wars, where the Senate appointed him dictator in 221 and 217 BCE. The Fabian Strategy is named after his efforts to delay and frustrate Hannibal Barca’s advance through Italy while Rome built up its forces.

Fabius Maximus is a prime example of how a leader can subdue the enemy’s troops with little fighting.

During the Second Punic War against Carthage, he realized Hannibal was too strong to defeat in open battle. Instead of engaging Hannibal directly, Fabius Maximus adopted a strategy of avoiding direct confrontation and engaging in hit-and-run tactics.

He harassed Hannibal’s troops and weakened them through attrition, which ultimately contributed to Rome’s victory in the war. Fabius Maximus also captured cities through subterfuge.

When Hannibal’s forces occupied the city of Tarentum, Fabius Maximus decided not to attempt a costly siege to retake the city. Instead, he used a clever ruse to deceive the enemy and infiltrated the city under the guise of a group of traveling musicians. Once inside, his forces attacked and captured the city without having to lay siege to it.

5) Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius was born around 157 BCE into a well-off family in Cereatae. Scipio Aemilianus recognized his military aptitude during an expedition to Numantia.

This began his rapid rise through the Roman army, where he was also a rival of his own protégé Sulla. He is credited as the victor of the Cimbric and Jugurthine Wars (a claim shared with Sulla). Besides his military exploits, he engaged in significant reforms of the Roman army, introducing large-scale logistical reforms.

Marius trained his troops in new methods of warfare, such as the use of the pilum, a javelin that could penetrate shields and armor. He also created specialized units of soldiers, such as the Numidian light cavalry, which were highly effective in hit-and-run attacks. These tactics allowed Marius to win battles without incurring heavy losses.

Marius was a master of political maneuvering and diplomacy, which he used to avoid the need for long sieges. He formed alliances with local leaders and persuaded them to surrender their cities without resistance.

In one example, Marius convinced the leader of the city of Jugurtha to surrender by offering him a pardon and a position in the Roman government. This strategy saved time and resources that would have been spent on lengthy sieges.

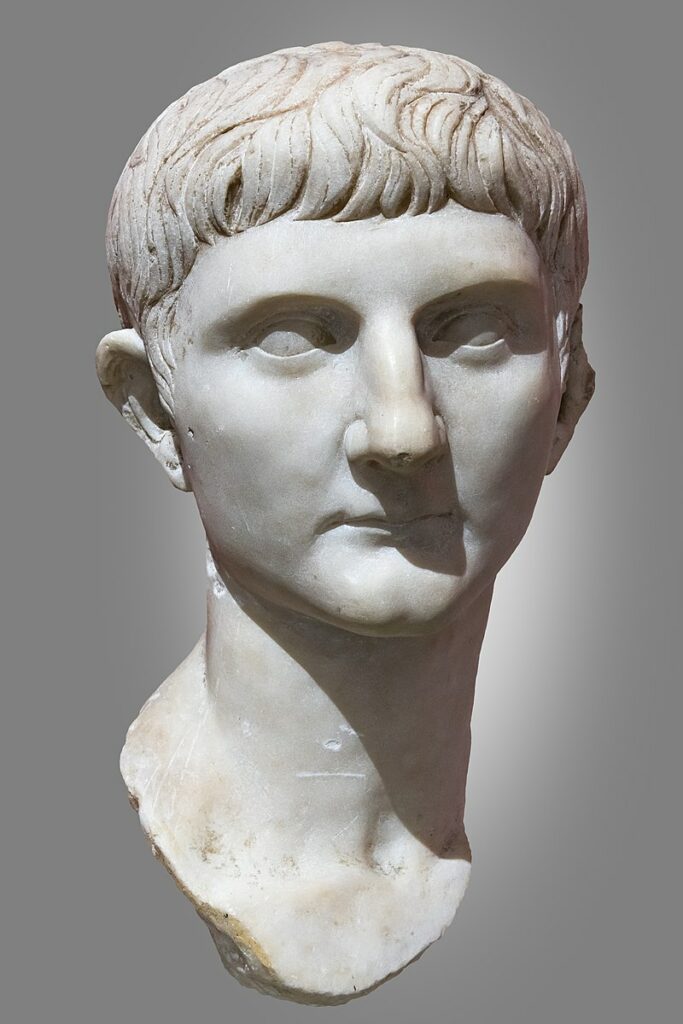

4) Trajan

Trajan was born into a senatorial family in 53 CE, which gave him access to the upper reaches of the army.

In 89 CE, he was commanding Roman forces in Spain. He supported Emperor Domitian against a revolt by troops along the Rhine, which brought him in favor of Rome.

Domitian was succeeded by Nerva, who was not popular with the army. In exchange for their support, Nerva agreed to make Trajan his heir. He subsequently took the throne in 98 CE, after Nerva’s death. During his reign, Rome conquered Dacia, Armenia, and Mesopotamia, bringing Rome to its greatest territorial size.

One of Trajan’s most prominent tactics was diplomacy. He negotiated with neighboring kingdoms to secure alliances and trade routes, demonstrating his diplomatic skills.

He also used his army’s speed and agility to surprise his enemies and strike before they could prepare. Trajan’s quick movements allowed him to capture cities without laying siege to them, as Sun Tzu suggests.

Trajan’s propaganda skills also proved effective. He offered generous terms of surrender to his enemies, promising to spare the lives of those who surrendered and even offering them jobs in the Roman army. This allowed him to win over the hearts and minds of his enemies’ troops.

However, Trajan was not afraid to engage in siege warfare when necessary. He captured heavily fortified cities such as Babylon and Hatra, but only after exhausting all other options.

3) Augustus

Augustus, born Gaius Octavius, was the great-nephew of Julius Caesar. Caesar adopted him and named him heir in his testament. However, his accession did not go unchallenged after Caesar’s assassination in 45 BCE.

Instead of engaging in warfare, he formed a Triumvirate with two other dictators, who split Roman possessions among them. However, this grouping soon splintered.

Lepidus, one of the other dictators, was exiled in 36 BCE, and Octavius defeated Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, leaving him in sole charge. During his reign, he annexed Egypt, Dalmatia, Pannonia, Noricum, and Raetia. He also completed the conquest of Hispania.

In 27 BCE, he took the title of Emperor (Caesar) and changed his name to Augustus.

One of Augustus’ key tactics was to use diplomacy and propaganda to secure his power. He understood the importance of winning over the hearts and minds of his people.

He used every opportunity to promote himself as a wise and benevolent ruler. He was adept at presenting himself as the embodiment of Roman virtue and patriotism, and he worked tirelessly to build a cult of personality around himself.

Augustus also understood the importance of strategic alliances. He formed alliances with key military commanders and influential senators to consolidate his power and expand his influence.

He also employed a divide-and-conquer strategy. He played various factions within the Roman Senate against each other to weaken their power and strengthen his own.

Besides these political tactics, Augustus also invested heavily in the military. He reorganized the Roman legions, created a standing army, and built a powerful navy. His military campaigns were swift and decisive, relying on a combination of strategic surprise, superior tactics, and overwhelming force.

2) Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio was born in 236 BC into a patrician family. His father was a famous general in his own right. Scipio followed him into the military.

He was the architect of the ultimate defeat of Hannibal Barca during the Second Punic War. Scipio brought Rome back from the defeat at Cannae in 216 BCE.

He was a young soldier in the army of his father-in-law, Armelius Paulus, who was killed in the battle. The younger Scipio then joined his father and uncle campaigning in Spain. After their disastrous defeat in 211 BCE, Scipio took over command of the forces there, eventually defeating Hannibal before the gates of Carthage.

One way that Scipio achieved these ideals was by using deception to his advantage. For example, in the Battle of Ilipa, he lured the Carthaginian general Mago away from his main force by leaving a small detachment of troops in plain sight.

This made Mago believe that he had found an opportunity to attack. However, Scipio had set a trap, and when Mago attacked, Scipio’s main force surrounded and defeated him.

Scipio’s most famous achievement was his defeat of Hannibal at the Battle of Zama. Rather than engaging in a confrontation with Hannibal’s superior cavalry, Scipio used his cavalry to harass and disrupt the Carthaginian forces. His infantry engaged in a series of skirmishes and feigned retreats to lure Hannibal’s troops into a trap. This allowed Scipio to win a decisive victory without suffering heavy losses.

1) Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a patrician family in 100 BCE.

As a teenager, he was drawn into the conflict between his uncle, Gaius Marius, and Lucius Sulla. After Sulla won, it was only his maternal connections to Sulla’s followers that saved him from exile, or worse.

However, this loss of status left him with only the military as a career option. Caesar felt it would be safest for him to serve far from Rome, so he joined campaigns in Asia and Cilicia, serving with distinction.

After Sulla’s death in 78 BCE, he returned to Rome. In 69 BCE he was elected a military tribune. This was the first step in a 25-year military and political career that put him at the pinnacle of Roman society after campaigns stretching from Gaul to Spain to Britain.

On the battlefield, Caesar was a master of speed and surprise, catching his enemies off guard with unexpected attacks and swift maneuvers. He adapted his strategies to the terrain and conditions of the battlefield. He anticipated his enemies’ moves and countered them effectively.

Caesar was also a brilliant tactician, using intelligence gathering to plan his campaigns more effectively and gain an advantage on the battlefield. He used spies and informants to gather information about his enemies’ movements and intentions. This allowed him to plan his campaigns more effectively.

The one common element that these generals had was that they left Rome, whether the Republic, Empire, or Byzantium, in a stronger position after their efforts. Rome’s leaders preserved a complex and fractious society for almost a millennium in the face of external foes and internal strife.

Belisarius’s efforts, in combination with Justinian’s reforms, set the stage for another century of Byzantium before the last vestiges of the empire were finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1453.

References

Alexander, Bevin, How Great Generals Win (New York: W.W. Norton, 1993)

Cowley, Robert and Geoffrey Parker eds., The Reader’s Companion to Military History (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996)

Giles, Lionel, Sun Tzu on the Art of War (London: Luzac, 1910) at https://ia804507.us.archive.org/16/items/artofwaroldestmi00suntuoft/artofwaroldestmi00suntuoft.pdf

Keegan, John, A History of Warfare (New York: Vintage, 1993)

Van Creveld, The Art of War: War and Military Thought (London: Cassell, 2000)