The Donner Party is a name synonymous with tragedy, desperation, and survival.

Their story is one of adventure and the pursuit of a better life. The bonds of family and community held together this group of pioneers as they set out to cross a continent. It is also a story of tragedy, the human cost of exploration, and the greatest limits of endurance.

This band of migrants set out for California in 1846. Their journey quickly became a nightmare as they faced a series of setbacks and delays. Their ordeal culminated in a brutal winter spent stranded in the mountains, where many members died, and others resorted to cannibalism to survive.

The Donner Party is a harrowing, unbelievable saga. The events leading up to their ill-fated journey, the challenges they struggled with along the way, and their ultimate fight for survival serve as important lessons to us all.

The Journey Begins

Throughout the 19th century, the western migration of many Americans across the continent continued unabated.

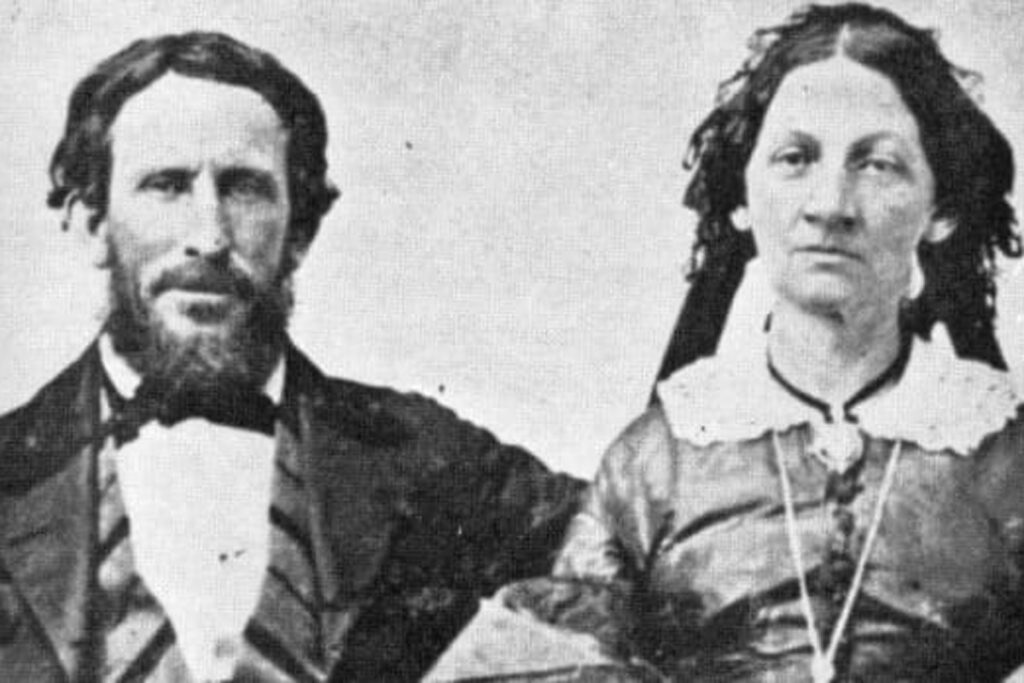

In the spring of 1846, a small group of pioneers led by the families of George and Jacob Donner and businessman James Reed left Springfield, Illinois, left for the fertile farmlands of central California.

There were just over 30 people in the group. This included multiple employees and teamsters. They made good progress for about a month until they reached Independence, Missouri. There, they joined a larger wagon train that was headed west as well.

Multiple families joined the growing group at this point. Lavinia Jackson Murphy, a widow with seven children, and Thomas Rhoads and his massive family – making up 12 wagons and 38 members – found their way into the now-enormous wagon train.

The pioneers continued westward on the Oregon Trail for the next two months. They reached Fort Laramie by mid-June and followed the route further until they reached the Little Sandy River in Wyoming a month after that, in mid-July.

It was here, however, that the Donner and Reed families decided to make a slight change to their itinerary. On July 20, 1846, the massive wagon train split. The majority opted to take the established trail westward towards Fort Hall, from where they would continue on the Oregon Trail to the coast.

However, a smaller contingent decided to continue southward, to Fort Bridger. This was a less-trodden part of the trail, and they needed a leader. George Donner stepped in.

The initial journey was filled with hope, excitement, and optimism. But the Donner Party soon faced many challenges and obstacles which tested their strength, and resilience, and ultimately took their lives.

Hastings Cutoff & A Fatal Miscalculation

The party elected George Donner as its leader. At its peak, the party numbered 87 people in 23 wagons. The Donner Party set off for Fort Bridger.

Traveling to the fort moved forward with little issue and the group made decent progress. However, an untrustworthy guide, Lansford Hastings, sent riders out to promote his new route – the Hastings Cutoff – a shortcut to California.

Instead of turning north from Fort Bridger and following the reliable Oregon Trail, the Hastings Cutoff advocated for continuing southwest. This cut over the Wasatch Mountains, into the Salt Lake Valley, and across the Great Salt Lake Desert.

Convinced by Hastings’ claim that it would cut 300 miles from their journey, the Donner Party decided to take his route. Though they were warned against it by an old friend, they chose to press ahead.

The reality was that the Cutoff was 125 miles longer than the established trail. It led them through some of the most hostile terrains in the Great Basin.

The Donner Party entered the Cutoff on July 31. They made good progress during the first week, but they lost about two weeks as they crossed through the unwelcoming mountains. They also faced significant challenges crossing the desert and the Ruby Mountains. This resulted in lost cattle, abandoned wagons, and valuable time.

By the time they reached the Humboldt River, where they could rejoin the main California Trail, it was late September. They lost about a month’s time. They were now racing to cross the Sierra Nevada passes before the harsh winter weather set in.

The Hastings Cutoff turned out to be a disastrous decision for the Donner party. It ultimately resulted in one of the most infamous tragedies in American pioneer history.

Trapped at Donner Lake

Exhaustion, anxiety, and fear began setting in for the group. Reed was banished to go the trail alone after a fight led to him killing one of the other men. Morale was low and cracks were forming in the group as they approached Donner Pass on October 31.

Their situation quickly turned from bad to worse. Snow began to fall in the mountains, and with each day it deepened. Eventually, they could go no further.

As they waited for the snow to stop, they hastily constructed cabins near Donner Lake and Alder Creek. The oxen, their main food source, wandered off and were lost. The snow continued and winter set in, trapping the Donner Party in the mountains. They failed to cross the mountains in time.

Weeks passed and by December, many members of the group were suffering from malnutrition. Baylis Williams died at the lake camp, the first death thus far. The situation worsened as snowfall continued, and the group was stranded in the mountains with dwindling food supplies.

With no other options, many members of the party were forced to resort to eating mice and chewing on boiled oxhide. Many others perished. The Donners, who camped a bit further down the mountain pass than the main group, soon saw Jacob and three hired men lost to the elements.

As each day passed, the Donner Party’s harrowing situation worsened. This led to many having to make the toughest, unthinkable, decisions to stay alive.

Desperation, Survival, and Cannibalism

On December 16, a small group of 15 embarked on a mission to cross the pass and seek rescue. This was the party’s only hope of survival.

The party named themselves the “Forlorn Hope.” They endured a month’s worth of overwhelming hardships, including cold, storms, deep snow, and inadequate food. This quickly led to the deaths of several of the men. In just the first few days, they were already lost and snowblind.

After several days without food, they resorted to the unthinkable – cannibalism – to stay alive. Despite the initial refusal by some members, it soon became their only option.

They first considered killing some of their group for food. But soon, the forces of nature would make that unnecessary, as the deaths began to mount. The survivors took the muscles and organs from the bodies of the already deceased men. They ate what they could stomach, and dried the rest for storage.

This went on for weeks. Eventually, those that remained stumbled upon a Native American settlement where they were given acorns, grass, and pine nuts to eat.

In the end, only seven members of the party survived. The eight men who died were cannibalized and eaten. The survivors were eventually rescued. Their journey from Donner Lake had taken a lengthy 33 days.

Whatever one thinks of their decision to resort to cannibalism, their story highlights the desperate measures humans can resort to when faced with extreme circumstances, and the lengths they will go to survive.

Aftermath and Rescue

After the remnants of the group made it out of the mountains, they were able to put together a formal rescue party. This rescue party left Fort Sutter on January 31. Multiple relief efforts and rescue parties followed.

In the intervening weeks, many of the survivors back at camp were also forced into cannibalism. The final survivor, Lewis Keseberg, reportedly sustained himself for weeks on the bodies of Mrs. Murphy and others. He did not leave the camp until April 21.

All in all, 47 members of the Donner Party survived the ordeal, while 42 perished in the mountains.

The tragedy of the Donner Party highlighted the incredible risks involved in the great overland trek. But it did little to slow the pace of migration in the coming years. It didn’t discourage many from taking the journey.

The Donner Party disaster also had a profound impact on the way we view cannibalism. The survivors’ decision to resort to cannibalism to stay alive has been the subject of much debate and controversy over the years. Some argued that it was a necessary evil, and others condemned it as an unspeakable act.

In the end, their story has left behind a deep, lasting legacy. Their trials and tribulations represent a cautionary tale about the dangers of adventure and exploration and a reminder of the challenges that many pioneers had to overcome as they trekked across the continent.

Their saga has been retold in numerous books, articles, and movies, and continues to fascinate people today.

References

“Donner Party.” California Pioneer Heritage Foundation, California Pioneer Heritage Foundation, https://californiapioneer.com/historic-events/donner-party/.

“Donner Party.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 Mar. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Donner-party.

Worrall, Simon. “Beyond Cannibalism: The True Story of the Donner Party.” Book Talk, National Geographic, 2 July 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/donner-party-cannibalism-nation-west.