The Crimean War, only a portion of which involved combat on the Crimean Peninsula, pitted Imperial Russia against the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, and France. It eventually involved Austria and the Kingdom of Sardinia as well.

Led by Great Britain and France, they saw themselves as balancing the great Russian bear. The war ended in a defeat for Russia. Extreme shifts in the European order that were established after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, reverberated until it collapsed in 1914.

Political Turmoil After the Napoleonic Wars

Europe was shaken up by the Napoleonic Wars that lasted from the 1790s until Napoleon’s eventual defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815.

Exhausted by interminable conflict, European leaders met in Vienna even before Waterloo. The purpose of these meetings was to start crafting a carefully balanced system of power that they hoped would end the conflict in Europe forever.

Crafted by Count Metternich of Austria, this system would eventually be called “realism” and would dominate European international politics for over a century. Great powers would “balance” each other’s interests to deter violent action.

The major power – Great Britain, France, Austria, Russia, and the Ottoman Turks – would act as guarantors of maintaining the balance of power so that conflict between smaller powers would not escalate into a major European war.

This system did not work well for long. The central issue was the fading power of the Ottoman Empire and its failing grasp on territories, many of them Christian, that caused wars of secession.

Revolutions in the Territories

The first of these, the Greek Revolution, started a mere six years after the Congress of Vienna.

Following these, the Egyptians rebelled, France took over Algeria, and the Balkans became a restless province. Serbia won its nominal independence in 1830 (the same year Greece became fully independent). Following this, areas of modern Romania and Bulgaria also began agitating for their independence.

Meanwhile, the Russians had driven out the remaining resistance to their rule along the northern Black Sea coastline and into the Caucasus, putting them in direct contact with the Ottomans for the first time in over a century.

The Russians saw themselves as protectors of Orthodox Christians (which included the Greeks and the Serbs) throughout the Ottoman Empire. This included the community in Palestine that lived around the Christian holy sites in Jerusalem.

The immediate catalyst for Greek and Serbian independence was the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-29. This resulted in a Russian victory that advanced the borders of Russia in the Caucasus. It also eliminated any Turkish footholds on the northern Black Sea coastline.

It also put Russian troops on the Danube in the Balkans through its “protectorate” of the provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia, in what is now Romania and Moldova. This “protectorate” would not end until after the Crimean War.

Britain and France looked upon these developments with some concern. Their colonial interests in the Eastern Mediterranean depended in part upon the buffer of the Ottoman Empire, keeping Russians out of the area.

The British and Russians were also engaged in “The Great Game” in Central Asia. Tensions over everything from Afghanistan to Persia emerged as a catalyst for strong British support of Ottoman power to counteract that of Russia.

Following this war, Russia built up its naval forces on the Black Sea, concentrating on the port of Sebastopol on the Crimean Peninsula. An ongoing source of tension between the Russians and the Ottomans was Russian access to the Dardanelles.

This allowed Russia to transfer ships from its frequently icebound ports to the ice-free ports along its southern coast. To do this, they had to sail right past the Ottoman capital of Constantinople. Treaties were signed and broken throughout this period that guaranteed passage to warships through this critical waterway.

Tensions Between European Powers and Russia Increase

As Britain and France engaged in colonial adventures around the globe, Russia felt like it was being treated to a double standard as it sought to protect its interests in the South.

The crumbling power of the Ottomans signaled to the Russians that they had an opportunity to secure an exit from the Black Sea for the Russian navy. In a famous memo to Czar Nicholas I, Russian nationalist professor Mikhail Pogodin, wrote:

France takes Algeria from Turkey, and almost every year England annexes another Indian principality: none of this disturbs the balance of power; but when Russia occupies Moldavia and Wallachia, albeit only temporarily, that disturbs the balance of power. France occupies Rome and stays there several years during peacetime: that is nothing; but Russia only thinks of occupying Constantinople, and the peace of Europe is threatened. The English declare war on the Chinese, who have, it seems, offended them: no one has the right to intervene; but Russia is obliged to ask Europe for permission if it quarrels with its neighbour. England threatens Greece to support the false claims of a miserable Jew and burns its fleet: that is a lawful action; but Russia demands a treaty to protect millions of Christians, and that is deemed to strengthen its position in the East at the expense of the balance of power. We can expect nothing from the West but blind hatred and malice…. (comment in the margin by Nicholas I: ‘This is the whole point’).

On the other side, France found itself under a new Emperor Napoleon after 1848. Napoleon wanted to legitimize himself on the European scene. He found a foil in countering Russian activities in the Near East.

Britain switched between taking advantage of Constantinople’s troubles and supporting it. Giving the Russians unfettered access to the Mediterranean was not in London’s interests.

The War Breaks Out

In response to a French and Ottoman provocation in Palestine, Russia militarily occupied the Ottoman Danubian provinces of Wallachia and Moravia in the summer of 1853. This prompted an Ottoman declaration of war a few months later. The British and the French supported the Ottoman declaration.

Russian forces immediately began offensives in both the Caucuses and the Balkans. The Ottomans stopped the Russians in what is now Bulgaria. Russian gains in the east prompted the Turkish fleet to sortie into the Black Sea to relieve their besieged forces.

The Russian Black Sea fleet trapped and destroyed this force at the Battle of Sinop in November.

The Turkish defeat, which essentially left the Dardanelles open to Russian naval assault, alarmed the British and French. In January 1854, British and French naval forces entered the Black Sea and forced Russian naval forces to withdraw to their protected anchorages.

With their fleets in the Black Sea, the British and French attempted to force the Russians to withdraw their forces from Ottoman territory. In February 1854, they demanded that the Russians immediately begin a withdrawal from the Danubian Principalities.

The Russians refused this demand. This refusal provoked an immediate declaration of war from London and Paris.

Russia hoped the Austrians would support its actions, but they refused to promise Austrian neutrality in the conflict. Thus, the balance of the Holy Alliance did not correct itself to prevent a major European War.

Even though the Russians subsequently withdrew from Wallachia and Moravia, leaving them as an Austrian protectorate, the British and French continued the war.

They aimed to remove Russian threats to the Dardanelles once and for all.

Allied Land Campaigns

The Allies now determined that the only way to destroy Russia’s ability to threaten Turkish interests was to destroy its fleet and the ports that harbored them.

Their first target was Sevastopol. After a desultory buildup, the British and French landed east of Sevastopol in the Bay of Eupatoria, surprising the Russians.

Wheeling around to encircle Sebastopol from the north, the 55,000 Allied troops encountered the 37,000 Russian defenders at the Alma River on the 20th of September. After a pitched battle that cost the Allies 4,000 casualties and the Russians about 5,000 men, the Russians withdrew from their positions.

The Allied commanders refused to pursue them, missing a chance to grab Sebastopol on the fly. After scouting the area, the Allies thought the Russian defenses were too strong but missed the fact that they were sparsely manned at this point.

Instead, the Allied commanders worked their way around to the south over the following weeks, hoping the defenses there would be weaker. This gave the Russians time to regroup and strengthen the southern defenses. The result was the siege of Sevastopol, which lasted from October 1854 to September 1855.

During this period, the Russians staged several attempts to break the siege, most notably the Battle of Balaclava on October 25, 1854, when the Russians attempted to take the Allied resupply base in Balaclava.

Notable in this battle was the famous Charge of Light Brigade when a brigade of British cavalry, acting on unclear and misunderstood orders, charged a battery of Russian guns, resulting in the loss of almost 50% of their number.

Overall, the Battle of Balaclava and the Battle of Inkerman in November, another Russian attempt to break from the siege, were still Allied victories. These actions pinned the Russians in the port for the next 11 months.

It was the weather that was the bigger opponent for the Allies. On the 14th of November, a storm sank 30 Allied transport ships, most notably one carrying the bulk of the winter clothing for the army. Overland transportation from Balaclava to the besieging troops became a sea of mud and disease ravaged the troops on all sides.

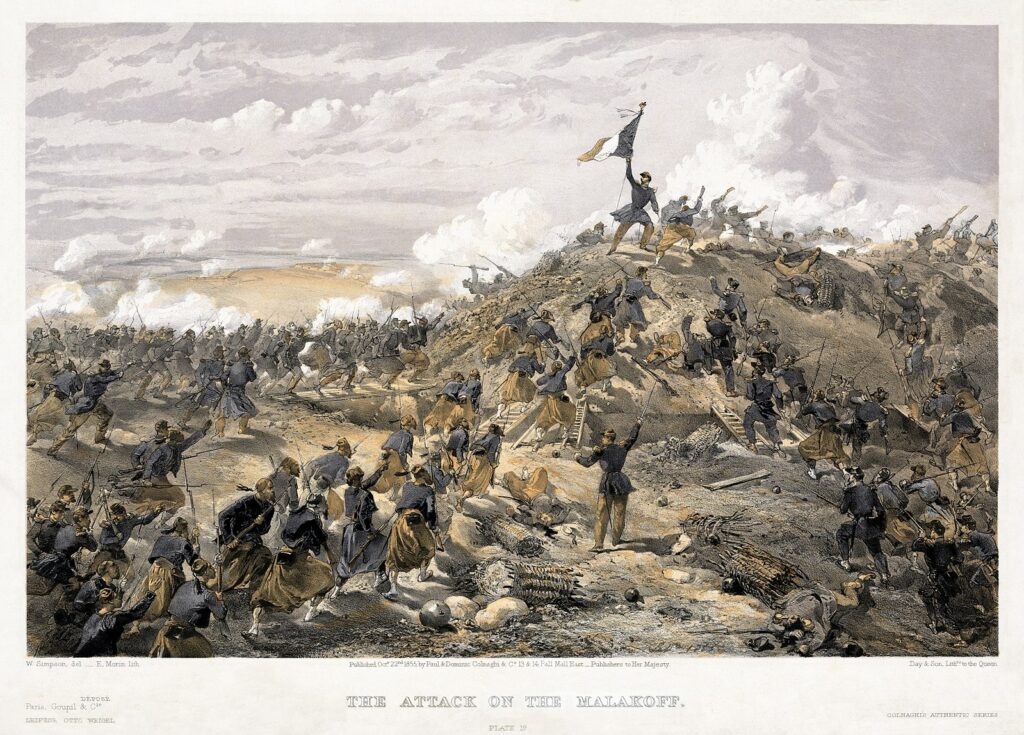

In June 1855, the Allies renewed their assault on the city. The Battle of Malakoff on June 18 accomplished little other heavy losses on the Allied side. Russian sorties were similarly repulsed. Both commanders, Lord Raglan on the British side and Admiral Nakhimov died. Raglan from exhaustion and Nakhimov in action.

Over time, the Allies built up an advantage in artillery and this finally resulted in the city’s fall on September 9th. Parallel to the Crimean actions, the Allies also launched assaults on other Black Sea ports in Kerch and Taganrog, both of which were taken but with little further action.

By this point, the bulk of the Russian fleet lay at the bottom of Sevastopol harbor.

The Baltic Theater

An often overlooked theater in this war was the British and French efforts in the Baltic Sea. This portion of the war played a crucial part in cutting off most Russian trade. The Anglo-French fleet blockaded the Gulf of Finland and bottled up the much smaller Russian Baltic Fleet.

While Russian fortifications resisted attempts to destroy Russian ships in Sveaborg (in modern Finland), it was clear that the Allies were slowly gaining the upper hand in this theater only miles from the Russian capital in St. Petersburg.

The Baltic threat also prevented the Russians from using their overwhelming manpower strength against the Allied forces operating in the south. The threat of an amphibious landing given Allied control of the seas was always present.

It was threats in this theater that finally forced the new Czar Alexander (Nicholas had died in March 1855 from pneumonia) to the negotiating table.

Peace and Aftermath

The Treaty of Paris ended the conflict in March 1856.

Russian troops withdrew from all parts of the Ottoman Empire and the Allied forces withdrew from the Russian ports they had seized in the Black Sea. The Russians promised to demilitarize the Black Sea coast. In exchange, the Ottoman Empire was admitted to the Concert of Europe.

The outcome of the war humiliated the Russians. There was a direct impulse to modernize Russian society, which resulted in the abolition of serfdom in 1860. It also influenced the Russian decision to sell Alaska to the Americans. St. Petersburg decided it was indefensible against the British.

Seeds of instability were sown by the Treaty of Paris that would haunt Europe in the coming decades. Balkan questions continued to bedevil European politics. The Ottoman Empire continued to decline in power despite its participation on the victorious side.

A series of wars in the Balkans continued for the next 50 years, with Austria, Russia, and the Ottomans supporting various sides. These conflicts were to provide the tinderbox that would start World War I and lead to a century of warfare thereafter.

Starting in 2014, Russia began employing its military to reassert its control over the Black Sea. Once again, the Western Allies, this time joined by the United States, feel compelled to resist Russian expansionism.

It should come as no surprise that Crimea and Sevastopol are again flashpoints in this conflict.