The term “ghost town” is used to describe a town quickly erected for a lucrative industry, which just as rapidly is abandoned once the source of wealth dries up.

Usually, these are towns out West that sprung up during the gold rush in the 1800s, but what does a modern ghost town look like?

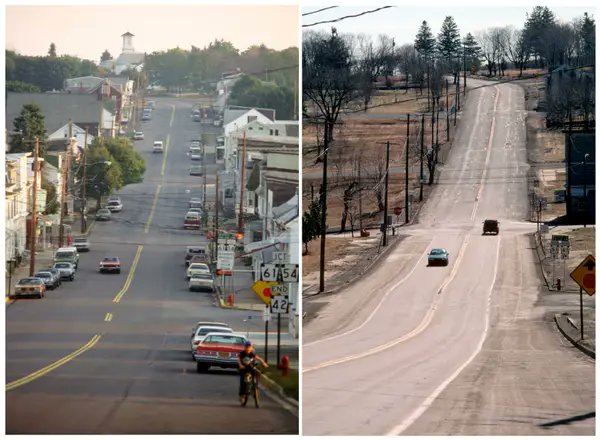

Centralia, Pennsylvania is perhaps the most infamous modern American ghost town, with its driveways leading to empty lots, constant low-lying steam which inspired the movie production Silent Hill, and once upon a time, a highway full of graffiti, all the result of the fire that has raged beneath the town for over 50 years.

Early history of Centralia

Located in central Pennsylvania, Centralia was founded in the mid-1800s after coal companies flocked to the large deposit of anthracite coal there.

At its peak, the town boasted a population of nearly 3,000 people, with a bustling economy centered on mining. However, the Great Depression took a toll on the town, resulting in most of the mines closing.

By the 1950s, the town had just over 1000 residents left, and the mine shafts were abandoned, replaced with bootleg miners, strip mines, and open-pit mines.

Without the economic lifeline of coal mining, the town of Centralia struggled. One result of Centralia’s economic decline was a decrease in government funding, which resulted in subpar social services such as trash management.

Several illegal landfills appeared across town as a means of managing waste, which resulted in sanitation, safety, and vermin issues. With limited resources to centralize trash deposits, the town resorted to converting an old strip mine into a landfill, coating the mine in inflammable material as a safety precaution against spontaneous combustion.

The Centralia Mine Fire

There are many theories as to how the Centralia mine fire may have started, but the most widely accepted is that on May 27, 1962, the City Council approved the use of fire to clear the landfill to make the town more inviting for upcoming holiday celebrations.

Although firefighters eliminated the waste with a controlled fire on that day, they had to return to the landfill multiple times over the next few weeks due to reports of trash still smoldering.

It was during one of these subsequent attempts to put out the fire that bulldozers discovered a hole in the base of the dump, after moving a pile of garbage which had prevented the workers from laying inflammable material across the entire mine.

This created an access point for the flames created by the firefighters to enter the coal deposit and slowly spread throughout the acres of abandoned mines beneath the town.

Although people were aware of the fire, estimates for the cost of containing it were astronomical compared to state budgets and the residents of Centralia decided to simply let it burn, believing it would eventually put itself out. It would not be for another twenty years that anyone realized just how far the fire would spread.

The fire spreads

By the late 70s, townsfolk were noticing strange occurrences in town. Near the landfill, there was a constant layer of steam escaping from the ground, which later spread across the whole town.

People began passing out in their homes, a phenomenon attributed to increased carbon monoxide levels as the gasses caused by the fires escaped the ground through people’s basements.

Then, in 1979, local gas station owner John Coddington was checking the fuel level of his tanks when he realized that the dipstick he was using was a bit warm.

After lowering a thermometer into the tank, he realized the gas was at 172 degrees Fahrenheit, nearly three times the average temperature of a tank of gasoline. Two years later, Centralia made national headlines when 12-year-old Todd Dombowski was nearly swallowed whole by a sinkhole opening in his backyard. He only survived by holding onto a tree root until his cousin could pull him out.

As the situation worsened, Congress passed a bill to protect the town’s citizens which allocated $42 million to relocate over 1,000 townspeople to new areas of the state. In 1992, the land in Centralia was claimed by the Pennsylvania government through eminent domain, and in 2002 the post office discontinued Centralia’s ZIP code.

A small number of townspeople remained, technically becoming squatters. But in 2013, the Pennsylvania government made a deal with the remaining 7 residents of Centralia that they could live their lives there and that their land would be claimed through eminent domain upon their death.

The end of Centralia

Although the fire has turned Centralia into all but a ghost town for residents, the town has attracted countless visitors over the years. A long stretch of PA State Route 61 in Centralia became a bizarre attraction, with tourists flocking to the stretch of road, which was cracked and worn from the collapsing mine shafts beneath it.

Countless visitors left their mark on the road with spray paint, and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 increased the number of visitors exponentially.

To avoid liability with the increase of visitors on the increasingly unstable land, Pagnotti Enterprises, which owns the land that the famous graffiti-covered highway was on, buried the highway with dirt. Petitions have been made to restore the highway, but with the ever-increasing potential for injury, it is unlikely that Pagnotti Enterprises will reverse its decision.

With the closing of Graffiti Highway and the remaining townspeople beginning to move or pass away, it seems that Centralia’s story is coming to an end.

The Pennsylvania government has ruled that it would be too expensive to fully extinguish the fire; estimates claim it could burn for the next 100-250 years before finally running out of fuel, and any plan to quench the fire or contain it exceeds the state budget.

As a result, the area will likely remain unpopulated for the foreseeable future, but its reputation as a ghost town with a fire burning just beneath the ground will still likely attract visitors for years to come.

References

Blakemore, Erin. “This Mine Fire Has Been Burning for Over 50 Years.” History Channel, June 12, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/mine-fire-burning-more-50-years-ghost-town.

Guss, Jon. “Inferno: The Centralia Mine Fire.” Pennsylvania Center for the Book, Fall 2007. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/inferno-centralia-mine-fire.

Krajick, Kevin. “Fire in the Hole.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 2005. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/fire-in-the-hole-77895126/.

Morton, Ella. “How an Underground Fire Destroyed an Entire Town.” Slate, June 4, 2014. https://www.slate.com/blogs/atlas_obscura/2014/06/04/centralia_a_town_in_pennsylvania_destroyed_by_a_mine_fire.html.