Billie Holiday was gifted with one of the most identifiable voices in the history of recorded music. It was a voice that throughout her 26-year career (and since her untimely death in 1959) has indisputably placed her among the all-time “greats.”

Songs like, “Them There Eyes” (1939), “Loverboy” (1941), “Good Morning, Heartache” (1946), and “T’ain’t Nobody’s Business If I do” (1949), represent an era when Jazz dominated the music scene. And no one represented it better than Billie Holiday.

From 1939 to her death in 1959, the US government pursued Holiday because she was black and wealthy. It started because she dared to sing a song called “Strange Fruit.”

It was a song whose imagery serves as a metaphor for dead bodies hanging from trees (like fruit). It sang of the victims of racist lynching in 20th-Century America.

In May of 1947, Holiday was ordered by FBI agents not to sing that particular song at a concert in Philadelphia. She ignored this warning.

That night, narcotic agents raided her hotel room. They then shot at her car as she was returning from the performance. She was later arrested on narcotics charges and sentenced to a year in prison.

FBI files from 1949 state that Holiday has been intentionally discredited to set an example to other “uppity” Blacks. One of the agents involved, Colonel George White, told a reporter that Holiday’s “fancy coats and fancy automobiles and her jewelry and her diamonds” generated much resentment among both Whites and Blacks.

White took it as his personal mission to put a stop to it.

Dire Beginnings

“Billie Holiday” was born Eleanora Fagan on April 7, 1915, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Clarence Halliday (a Jazz guitarist and banjo player) and 13-year-old Sarah Julia “Sadie” Fagan. Sarah had moved to Philadelphia after being forced to leave her parents’ home in Baltimore, Maryland, for getting pregnant.

Disowned by her parents, Sarah arranged for Eleanora to live with her older, married half-sister, Eva Miller, in Baltimore. Not long after Eleanora was born, Halliday abandoned his family to pursue a career as a musician. Eleanora began life in extreme poverty.

Sarah often took what were then called “transportation jobs.” These were serving jobs on trains available to both female and male Blacks. Ultimately raised by Eva Miller’s mother-in-law, Martha Miller, Eleanora grew up barely knowing her mother. She had to rely on virtual strangers for the first decade of her life.

Education and Employment

Eleanora attended kindergarten at St. Frances Academy (an independent Catholic school with ties to the Black and Hispanic communities). However, she frequently skipped school.

Her truancy resulted in spending nine months in the House of the Good Shepherd. This was a Catholic reform school for errant African-American girls.

At this point, Sarah (who now called herself “Sadie”) had opened a restaurant called the East Side Grill. Compelled to work long hours helping her mother at the restaurant, Eleanora formally dropped out of school at age 11.

On Christmas Eve, 1926, “Sadie” returned to discover a neighbor, trumpet player Wilbur Rich, in her home. He was attempting to rape Eleanora. This confrontation resulted in Rich’s arrest.

As a state witness in a rape case, Eleanora was returned to the House of the Good Shepherd. However, this time she was under protective custody.

Eleanora was released the following February. She found a job running errands and scrubbing the marble steps of a local brothel. She also washed floors for neighboring families.

It was while working at the brothel that Eleanora first heard the records of Jazz greats Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith. In her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, she cites the song “West End Blues” (written by Joe “King” Oliver) as one of her first musical inspirations.

Rising Star of the Night

In 1928, “Sadie” moved to Harlem, New York. She left Eleanora again, but with her half-sister’s mother-in-law, Martha Miller. The following year, however, Eleanora joined her mother there.

According to one account, upon moving to Harlem, Eleanora herself became a prostitute. They say that she was arrested and sentenced to four months in an asylum on Welfare Island (now known as Roosevelt Island).

By age 14, Eleanora was making a name for herself as a performer, singing in Harlem nightclubs. She took the name Billie (from Billie Dove, a White American actress she admired), and Halliday (from Clarence Halliday, her probable father).

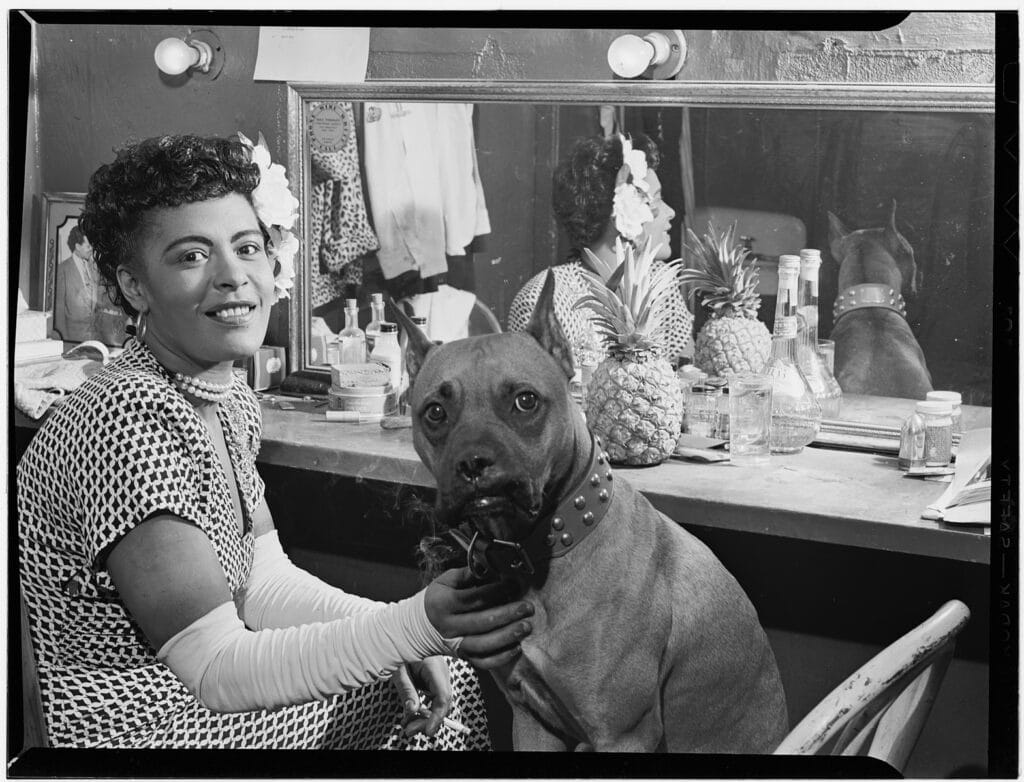

She started billing herself as “Billie Halliday” (eventually changing it to “Holiday”). Soon after, she adopted her trademark white gardenias, which we wore in her hair.

From 1929 to 1931, Holiday teamed up with tenor sax player Kenneth Hollan. They performed at clubs like the Grey Dawn, Catagonia Club, and the Brooklyn Elks Club. As her reputation grew, she performed in other hot spots including the famed Alhambra Bar and Grill.

As fate would have it, during this time she crossed paths and reunited with her father. He was now a popular musician in Fletcher Henderson’s Big Band and Jazz band.

Holiday’s Big Break

In late 1932, the 17-year-old Holiday replaced Jazz /Blues singer Monette Moore at the popular Harlem nightclub, Covan’s.

In early 1933, record producer John Hammond (who loved Moore’s singing and had actually come hoping to hear her) caught Holiday’s performance instead. Greatly impressed, Hammond arranged for Holiday to make her recording debut, with the legendary clarinetist Benny Goodman.

They recorded two songs: “Your Mother’s Son-in-Law” and “Riffin’ the Scotch.” The latter became Holiday’s first bonafide hit. “Son-in-Law” sold only 300 copies, but “Riffin’ the Scotch” sold an impressive 5,000!

Hammond would later say of Holiday, “Her singing almost changed my music tastes and my musical life, because she was the first girl singer I’d come across who actually sang like an improvising jazz genius.”

In 1935, Big Band leader Duke Ellington gave Holiday a small part in his short musical film, Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life. In the film, she sang “Saddest Tale,” a song written by Ellington.

Improvisation and Coming into Her Own

In 1935, Holiday was signed to Brunswick Records by producer John Hammond. She was to record with popular Jazz/Swing pianist Teddy Wilson, for the growing jukebox dance market. (1935 to 1946 was known as the “Swing Era” and was dominated by bandleaders like Benny Goodman.)

Holiday was encouraged to improvise with Wilson on the material. This contributed greatly to what would become Holiday’s signature style.

Their first improvised collaboration was a Harry Woods song called, “What a Little Moonlight Can Do.” It so impressed record executives that they decided to help Holiday launch a solo career.

For the next three years, Holiday worked with a variety of lyricists and musicians. This included Jazz tenor saxophonist Lester Young, with whom she collaborated on 45 songs. (It was Young who dubbed Holiday “Lady Day.”)

In late 1937, Holiday was hired as lead vocalist with renowned Big Band leader, Count Basie. They performed “one-nighters” in clubs across the East. Now growing in demand, Holiday was allowed to choose which songs she sang and contribute to the arrangements.

Basie later said, “When she rehearsed with the band, it was really just a matter of getting her tunes like she wanted them, because she knew how she wanted to sound and you couldn’t tell her what to do.”

During this period she recorded, “I Can’t Get Started,” “They Can’t Take That Away from Me,” and “Swing It Brother, Swing.” All of these became commercial successes. At the same time, a song she’d recorded the year before from George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess called “Summertime” became a hit.

Ironically, even with her growing popularity, in February of 1938, Basie fired Holiday for being “temperamental and unreliable.” She reportedly complained of low pay and poor working conditions. She refused to sing the songs requested of her or change her style.

Black Singer in a White Band

A month after being fired by Basie, Holiday was hired by popular bandleader Artie Shaw. This was the first time a Black female singer toured the segregated US South with a White bandleader.

Shaw was frequently confronted by the racial tension prevalent in the South. He was known to vehemently defend Holiday. He once said, “I want you on the band stand like [White female Jazz singer] Helen Forrest, [White male novelty singer] Tony Pastor, and everyone else!”

In one well-documented incident in Louisville, Kentucky, Holiday lost her temper with a heckler. She had to be removed from the stage.

In March of 1938, Shaw and Holiday performed live on New York City’s most powerful radio station, WABC. Due to their unqualified success, they were asked to return in April.

Several news and entertainment sources, including The New York Amsterdam News and Metronome, praised Holiday’s voice and their performances. They said, “the addition of Holiday to Shaw’s band put it in the top brackets.”

In May of 1938, Shaw won Battle of the Bands competitions against both famed band leaders Tommy Dorsey and Red “Mr. Swing” Norvo. The audience favored Holiday over their respective singers.

But despite Holiday’s success and popularity among both Whites and Blacks, racial prejudice reared its head in November of 1938. She was asked to use the service elevator at the Lincoln Hotel in New York City because White patrons of the hotel had complained.

Holiday left Shaw’s band a short time later.

“Strange Fruit”

In 1939, Barney Josephson, owner of an integrated nightclub in Greenwich Village called Café Society, brought a song to Holiday. It was based on a poem about lynching.

It was a song she’d heard the year before but resisted performing for fear of offending Whites. At Josephson’s behest, she acquiesced.

In her autobiography, she later wrote, “It reminds me of how Pop died, but I have to keep singing it, not only because people ask for it, but because twenty years after Pop died the things that killed him are still happening in the South.”

According to Holiday, her father, Clarence Halliday, was denied medical treatment for a fatal lung disorder. He was allowed to die because he was Black.

In April of 1939, record producer Milt Gabler agreed to record the song for his Commodore Records label. Quickly becoming Holiday’s biggest-selling record, “Strange Fruit” remained in her repertoire for the remainder of her career.

Recordings, Praise, Popularity

Between 1940 and 1944, Holiday recorded several popular songs including, “God Bless the Child” (which she co-wrote), “Trav’lin Light,” “No More,” “That Ole Devil Called Love,” “Big Stuff,” and “Don’t Explain” (which she also co-wrote).

On October 11, 1943, Life magazine declared, “[Holiday] has the most distinctive style of any popular vocalist, [and] is imitated by other vocalists.”

The following fall, record producer Milt Gabler signed Holiday to Decca Records. She recorded “Lover Man” (which reached #16 on the Pop Charts and #5 on R&B).

The success of this song made Holiday a cross-over mainstay of the Pop community. This success led to solo concert invitations; a rarity for Jazz singers of the 1940s.

Rise, Fall, and Reemergence

By 1947, Holiday was one of the most successful musicians in American history. She made $250,000 over the previous three years.

Riding high on popularity, in 1946, Holiday won the Metronome magazine popularity poll. She was ranked second in the DownBeat 1946-1947 poll, and she placed fifth in Billboard’s annual college poll of “girl singers.”

But on May 16, 1947, Holiday’s star came crashing to earth. She was arrested for possession of narcotics in her New York apartment; targeted by US Federal authorities. Arraigned on May 27, she was sentenced to one year in Alderson Federal Prison Camp, in West Virginia.

This drug conviction resulted in her losing her New York City Cabaret Card. It also barred her from working at any venue that sold alcohol (which most clubs did). Therefore, this limited her to performing at concert halls and theaters. Holiday was released from prison two months early for good behavior.

Fearful audiences rejected her because of her arrest. But in March of 1948, Holiday played Carnegie Hall to a sold-out crowd. (Twenty-seven hundred advance tickets were sold. This was a record at that time—particularly considering that Holiday’s last record in the charts was “Lover Man” in 1945.)

Following a series of single engagements, in early 1948, her promoter, Al Wilde, arranged a Broadway show for Holiday titled, Holiday on Broadway. Though it sold out nightly, it closed after just three weeks.

On New Year’s Eve, 1948, Holiday was involved in a brawl in Los Angeles and subsequently charged with three counts of assault with a deadly weapon. This drew the attention of federal authorities looking for cause to arrest her again. Three weeks later, FBI agents burst into her room at the Hotel Mark Twain in San Francisco and arrested her for opium possession.

While out on bail, crowds packed every venue she played.

Comebacks, Arrests, Heartache, Heroin

The last decade of Holiday’s life was a roller-coaster ride of comebacks, arrests, heartache, and a heroin habit she couldn’t shake.

By 1950, due to Holiday’s drinking, drug use, and extreme lifestyle, her health began to deteriorate. Even so, she was more in demand than ever.

In 1954, Holiday toured Europe. The tour was organized by London-born pianist Leonard Feather. They played in Sweden, Germany, Netherlands, France, and Switzerland.

Upon returning to the US, she was regarded as a superstar. She was rubbing elbows with Hollywood elite (and having affairs with more than a few, including actors Charles Laughton, Tallulah Bankhead, and Orson Wells).

On November 10, 1956, Holiday performed two concerts before packed audiences at Carnegie Hall. Live recordings of the second performance were later released on a Verve/HMV album in the UK titled, The Essential Billie Holiday. About that same time, her autobiography, Lady Sings the Blues, hit the bookstores.

The following year, Holiday made a memorable performance on CBS’s “The Sound of Jazz,” singing

“Fine and Mellow.” In 1959, she returned to Europe where she made one of her final television appearances, on Chelsea at Nine, in London.

Holiday’s final studio recordings were made for MGM Records in 1959, lushly orchestrated by Ray Ellis and his Orchestra. These recordings were released posthumously as simply, Last Recording.

The End and Aftermath

On July 17, 1959, Eleanora Fagan (“Billie Holiday”) died at the age of 44 from cirrhosis of the liver (presumably due to alcohol abuse). Many insiders contend that she was driven to alcohol and drugs by two decades of law-enforcement persecution.

Even on her hospital deathbed, federal authorities arrived to serve an arrest warrant for drug possession.

Billie Holiday’s music and extraordinary life have inspired numerous tributes including Nina Simone’s cover of “Strange Fruit.” Diana Ross had a beautiful portrayal of “Lady Day” in the film Lady Sings the Blues.

The US Postal System honored her with a postage stamp. Time magazine named “Strange Fruit” the “Best Song of the Century.” She was bestowed with numerous Grammy Awards (both in her time and posthumously).

In many regards, Billie Holiday’s popularity has only grown with time.

References

britannica.com., “Billie Holiday,” Billie Holiday | Biography, Music, Movie, Death, & Facts | Britannica

billieholiday.com., “The Official Website of Billie Holiday,” Bio – The Official Website of Billie Holiday

vanityfair.com., “Good Morning Heartache: The Life and Blues of Billie Holiday,” Good Morning Heartache: The Life and Blues of Billie Holiday | Vanity Fair

theguardian.com., “Singer, activist, sex machine, addict: the troubled brilliance of Billie Holiday,” Singer, activist, sex machine, addict: the troubled brilliance of Billie Holiday | Billie Holiday | The Guardian

grunge.com., “THE TRAGIC MEANING BEHIND BILLIE HOLIDAY’S ‘STRANGE FRUIT’,” https://www.grunge.com/338349/the-tragic-meaning-behind-billie-holidays-strange-fruit/

biography.com., “The Tragic Story Behind Billie Holiday’s ‘Strange Fruit’,” https://www.biography.com/musicians/billie-holiday-strange-fruit

mosaicrecords.com., “Lester Young and Billie Holiday,” https://www.mosaicrecords.com/lester-young-and-billie-holiday/

allmusic.com., “Billie Holiday,” https://www.allmusic.com/artist/billie-holiday-mn0000079016/biography

foundsf.org., “Billie Holiday Busted,” https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=Billie_Holliday_Busted

archive.org., Lady Sings the Blues, https://archive.org/details/ladysingsblues00holi_0/page/n1/mode/2up