Last updated on March 8th, 2023 at 05:34 am

The Renaissance was a period of major intellectual, artistic, and cultural innovations from about 1350 AD to 1630 AD.

The word “renaissance” is French for “rebirth,” but it would probably be more appropriate to use the Italian “Renascimento” since it was on the Italian peninsula that these transformations really first took root.

You’ve no doubt heard of at least some of the major figures of the Renaissance: Michelangelo, Raphael, and Botticelli, to name just a few.

Perhaps you’ve even heard of the Medici family, who funded many of the era’s greatest artists. But have you ever wondered why the Renaissance began in Italy?

To answer that question, let’s look at the primary reasons that made Italy the perfect breeding ground for this cultural transformation.

Italy Was the Birthplace of Rome

The first reason has to do with geography. Above all, the Renaissance was inspired by the classical works of antiquity.

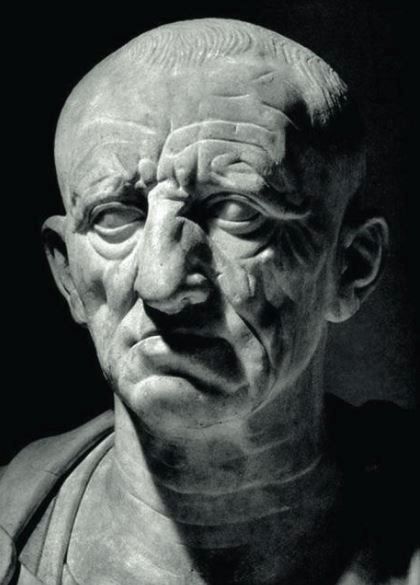

Namely, the works of classical Greek and Roman writers and artists provided the foundation for the outpouring of Renaissance creativity.

You see, Italians – that is, people who lived on the Italian peninsula – viewed ancient Rome and Greece as part of their cultural heritage.

To them, the past was superior to the present, and classical Roman civilization had much to offer in the way of its laws, its values, and its art.

They imitated ancient Greek and Roman artists while at the same time infusing classical values and aesthetics into their own original works.

Some of the main characteristics of these works of antiquity included a focus on nature, individualism, and secularism. These values all came together to form a cultural movement known as humanism.

Humanism was a fundamental part of what defined the Renaissance. Whereas God was the primary focus of art and philosophy during much of the Medieval era, humanism took a human-centric approach (hence the name).

While Christian themes still factored heavily in Renaissance art – think Michaelangelo’s David or the Sistine Chapel – there was also a clear emphasis on human anatomy and realism.

Fortunately for Italians who cherished classical works, they were surrounded by the past.

While scholars in other parts of Europe could transcribe classical Greek or Roman texts, it was quite another thing to visit the ancient ruins scattered throughout the lands of the former Roman Empire.

For example, Filippo Brunelleschi, who constructed the famous dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral in Florence, developed many of his architectural theories by studying ancient Roman ruins.

Besides the advantage of proximity, Italians of the Renaissance era also shared a common language with the Romans of the past. In the 14th century, there really was no Italy.

The territory that would later become the nation of Italy was divided up into several city-states that each competed, traded, and even fought with one another.

Moreover, each region had its own distinct dialect that often made communication difficult. In fact, when Dante wrote Divine Comedy in his native Tuscan language rather than in Latin, many people criticized his choice of language because many people had trouble understanding it.

But since Latin served as the common language on the peninsula, the writings of ancient Roman authors like Cicero and Tacitus were easily accessible to Italians of the Renaissance.

Therefore, humanist scholars traveled throughout the Italian peninsula and the rest of Europe, gathering classical manuscripts transcribed or translated to and from Latin. Francesco Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio were two of the most important figures to undertake this task.

Petrarch and Boccaccio

Francesco Petrarch lived from 1304 to 1374 and, during his lifetime, made enormous contributions to the revival of classical Greek and Roman literature and philosophy. Petrarch has often been referred to as the “father of humanism” for his work reviving classical texts.

Petrarch began reading ancient Greek and Roman authors as a teenager. Over time, his passion for the classics only grew.

One of his most important achievements was the discovery of Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Brutus, and Quintus, which he came upon in the Cathedral Library in Verona in 1345. These letters provided Petrarch with insights into the great Roman orator that had previously been absent.

His friend and fellow humanist, Boccaccio, was another contributor to the revival of classical works. Following in Petrarch’s footsteps, he translated the works of Ovid, Homer, and Tacitus from Greek into Latin and wrote an influential collection of biographies about important ancient women.

Because this was before the invention of the printing press, men like Petrarch and Boccaccio had to travel widely to access rare manuscripts.

They also developed a network of contacts throughout Europe who provided them with valuable materials. But there was one other unlikely source of valuable classical works: the Crusades.

The Crusades (Accidently) Played a Role

Specifically, the Fourth Crusade indirectly led to the availability of a wealth of new manuscripts. You may know the Crusades as a series of campaigns in which knights from the western Latin portion of Europe fought against Muslims for control of the Holy Land. That was what the first three Crusades had been about.

That was also the intention of the Fourth Crusade until things went awry. Due to a series of unintended events, the crusaders fought a series of side battles to repay the debts they had accrued over the course of their journey east. The culmination of these conflicts was the sacking of Constantinople.

Constantinople was a city rich in antiquity. As the capital of the eastern portion of the Roman Empire, it contained a treasure trove of ancient manuscripts hailing from the time of the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Muslims.

Even though Pope Innocent III had strongly condemned the city’s sacking, he realized the significance of these valuable sources of knowledge. He sent a group to the city to study with Greek scholars there.

Thus, the Fourth Crusade opened the doors to a new wealth of knowledge previously unavailable to western Europeans.

Suddenly, Italian scholars had access to Greek and Arabic works of science, art, and literature that provided even more material for the burgeoning Renaissance.

Money and Religion Fuelled Renaissance Art

Another crucial factor that led to the Italian Renaissance was trade. Italy was situated between Asia and the Mediterranean, which meant that a large amount of traffic – including people, goods, and ideas – moved through the peninsula.

In Florence, which for a time was the center of Renaissance activity, several families became incredibly wealthy due to a profitable wool trade and international system of banking.

First and foremost among these families was no doubt the Medicis. The Medicis were a powerful banking family whose members included four popes and two queens.

They had a powerful influence over Florentine culture and funded some of the best-known artists of the period, including Fillipo Brunelleschi, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo.

Another important source of patronage came from the city-states themselves. As previously mentioned, during the 14th through the 17th centuries, Italy was composed of various city-states that were in competition with one another.

One way a city-state could project its power was to fund public works of art or architecture. In a sense, art was a form of propaganda that helped one city-state increase its prestige.

During the Renaissance, a great work of art was just as much a reflection of the patron’s reputation and status as it was of the artist’s skill.

For that reason, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the Vatican also wanted to participate in public works of art.

Once Pope Martin V relocated the papal seat back to Rome from France in 1420, the Vatican became a major contributor to Renaissance art and architecture.

Since Rome didn’t conduct trade, it was funded solely by its domestic market. This included pilgrims and church bureaucrats living within the papal states of central and northern Italy and southern France.

It was important for the Vatican to maintain its claim over these lands in any way it could. One way to do so was by investing in armies. Another was by investing in art.

The commissioning of public art and architecture was a way for the pope to legitimize the Church’s power and to make it visible to its followers. To this end, the Church also continued the work of Petrarch and Boccaccio by transcribing ancient Greek and Roman texts.

As Pope Nicholas V once declared, “Not for ambition, nor pomp, nor vainglory, nor fame, nor the eternal perpetuation of my name, but for the greater authority of the Roman church and the greater dignity of the Apostolic See… we conceived such buildings in mind and spirit.”

Thanks to funding from patrons like the Church and the Medici families, Italy became the center of Renaissance thought and creativity.

Eventually, that hub shifted away from the peninsula. However, by the mid-15th century, northern European artists like Jan van Eyck were incorporating the ideas developed in Italy into their own works of art.

But those later beneficiaries owe a special debt to the Italian artists and scholars who first paved the way for a cultural transformation based on the ancient past.