Last updated on March 22nd, 2023 at 05:08 pm

Imagine if, at the end of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, the beast never transforms from a ferocious, hairy monster into a dashing prince.

And imagine that Belle isn’t a brave, beautiful girl with a loving, maternal instinct but an ordinary woman forced into marrying a freakishly hairy man she’s never met.

If you add those elements to Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, what you’re left with is closer to the actual events that inspired it.

Take a look at history, and you’ll see that the true story of this real-life couple is much more complicated than the version most of us are familiar with.

Pedro González

You see, the “beast” – whose real name was Pedro González – was not a beast and would have been quite offended to be referred to as such.

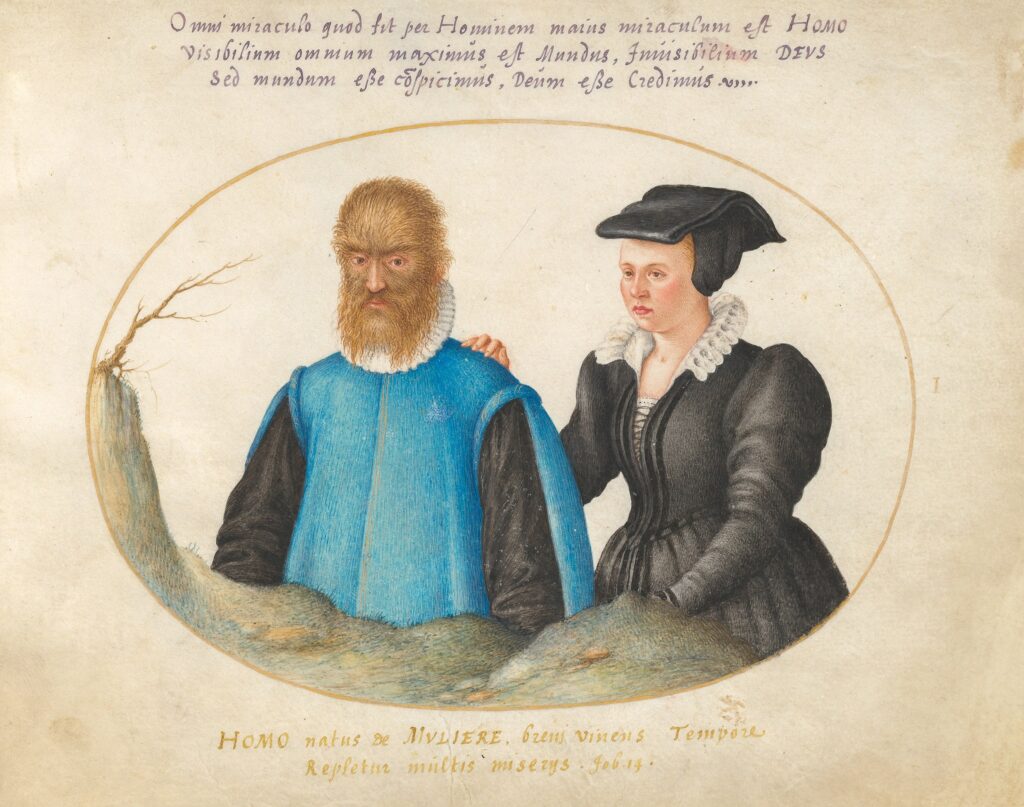

He was abnormally hairy, but it didn’t have to do with any evil enchantment. He was cursed with a rare genetic condition that caused his hair to grow unusually long and thick all over his body.

The condition, known as hypertrichosis, occurs in both men and women and can cause excessive hair growth on any body part.

In portraits taken of Pedro during his life, he’s shown with a face covered so completely by hair that his skin is barely visible.

Today, there are a handful of hypertrichosis cases, and those with the condition are sometimes scorned, bullied, and misunderstood.

But as hard as that may sound today, in 16th-century Europe, it was much more challenging to be accepted as an outsider.

At a time when people still believed that werewolves roamed the countryside and that wild men lived just beyond the limits of civilization, a man covered in what looked like fur was often treated more like an animal than a human. And that was precisely the society that shaped Pedro Gonzalez.

The Original Story of Beauty and the Beast

Pedro was no prince. He was most likely born on the island of Tenerife sometime around 1537, soon after which he was abandoned by his parents, probably due to his shocking appearance.

Beyond that, much of his childhood is murky. However, after being abandoned, there are indications that monks took him in, as it was common practice for monks to bring orphaned children into their monasteries.

In any case, a significant turning point in Pedro’s life came in 1547. What happened to him at this point depends on historical sources

One version is that French privateers spotted the boy and decided he would make an excellent gift for the newly crowned King Henry II of France.

Another possibility is that after exhibiting the boy around Spain, his father (who, in this interpretation, didn’t abandon him at birth) sold him off to the French king himself.

Either way, at about ten, Pedro was spirited off to France, where he would spend the next three decades of his life.

Life at the French Court

Pedro’s arrival at the French court caused quite a bit of excitement, and in any other monarchy, he would have been condemned to live out his life as a kind of strange fascination for the royal family and their visitors.

At the time, the monarchs of Europe liked to decorate their courts with people they saw as freakish or odd. Those who were unusually small in stature, obese, or showed signs of mental instability could find themselves put on display in Europe’s finest royal courts, where they were simultaneously marveled, mocked, and gawked at.

Fortunately for Pedro, King Henry II was drawn to scientific inquiry and had a special fondness for children. The boy piqued his interest and wondered what his unusual condition could reveal about human nature.

Instead of putting the wild man of Tenerife on display, the king decided to educate the boy. Thus, Pedro spent the next few years bouncing from one tutor to the next, learning etiquette, Latin, and horsemanship.

Pedro’s tutors included some of the court’s most important figures, and the king was impressed that Pedro seemed to learn just as well as any other aristocratic child. As a result, he granted him a stipend to study law at the university of Poitiers, France’s second most prestigious university.

Based on the documents that record his education and changing roles within the court, it’s clear that Pedro was accepted as an aristocratic gentleman. He even learned to dress like an aristocrat, wearing the ruffled collar reserved only for the privileged.

Still, one thing sorely absent in Pedro’s life was love. After all, who could fall in love with someone who appears to be only half-human?

It would take King Henry II’s passing, but eventually, the real-life “beast” would find his own personal Belle.

How beauty and the beast really got married

In 1559, King Henry II was doing one of the things he loved best – jousting – when he received a mortal blow that would indirectly lead to Pedro’s marriage.

After the king’s passing, Pedro was moved to the castle of Catherine de Medici, the king’s widow, who became his new protector.

It was Catherine de Medici who most likely arranged the marriage between Pedro and the daughter of a textile merchant named Catherine de Raffelin.

It’s unclear what the young woman thought of her husband-to-be or whether or not she was pressured into marrying the excessively hairy man. But it was common for lords and royalty to coerce their subjects into marriages when it pleased them.

For example, Pedro’s son, Enrico, who also suffered from hypertrichosis, married a woman from a remote village only after the Archduke of Parma pressured the bride-to-be’s father into accepting the arrangement.

What needs to be clarified is how the two met in the first place. While many stories claim that Catherine only discovered Pedro’s condition upon marrying him, we don’t know the full story.

However, we do know that many Europeans still considered Pedro to be more animal than human, even to the point that Pedro’s werewolf-like appearance made it difficult – if not impossible – for him to travel alone.

Considering superstitions and prejudices, it’s easy to believe that Catherine would have had some reservations about marrying Pedro.

Despite the historical unknowns, we also know that the couple eventually had seven children together, four of whom inherited Pedro’s condition.

Those four, sadly, were forced into the kind of childhoods that Pedro himself had been fortunate enough to avoid. Instead, they were studied, painted, and exhibited around Europe for crowds of eager spectators and noble families.

For Pedro, who knew all too well what it was like to be gawked at, the fate of his children must have been painful to bear.

Many people like to paint the story of Pedro as the tragic tale of a man whose strange genetic condition doomed him to a life of misery. It’s assumed that anyone who came in contact with him regarded him as a monster and treated him as such.

But this is only part of the story. There can be no doubt that Pedro experienced ridicule and cruelty throughout his life, but when you compare Pedro’s fate to that of other so-called freaks of the time, his life looks more like a blessing than a curse.

After all, even after King Henry’s passing, Pedro continued to integrate into Parisian aristocratic life. In 1582, he became a law professor at the Sorbonne, Paris’s most prestigious university. And whatever the true nature of Pedro and Catherine’s relationship, it was certainly long-lasting.

Their love might not make for a Disney movie, but it says something that when Pedro finally passed at the age of 80, after 40 years of marriage, he did so with Catherine by his side.

From Petrus Gonsalvus to Disney’s Beauty and the Beast

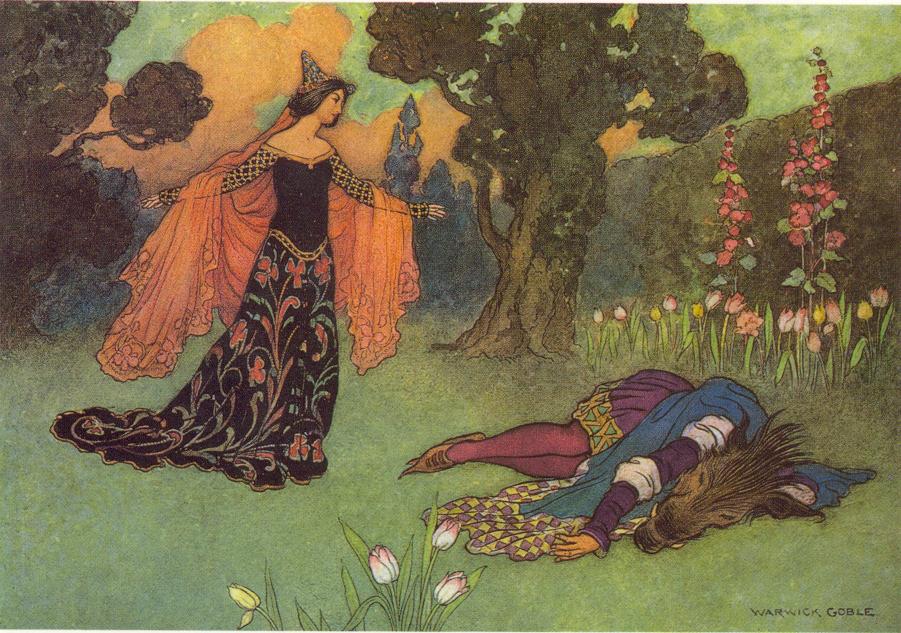

When Disney screenwriters began to write the 1991 version of Beauty and the Beast, they looked to a 1740 fairy tale of the same name, written by French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve.

Many scholars think that this early version of the Disney classic borrowed its plot from the story of Pedro Gonzalez, which is why Pedro’s story can now be considered the raw material behind the classic fairy tale.

But it’s not just the wild man from Tenerife who may have inspired Beauty and the Beast. Stories about young women falling in love with half-animal brutes go back thousands of years to the days of ancient Rome.

The oldest known tale that fits this mold is Cupid and Psyche, a myth from the second century AD. In the Roman myth, the beautiful Psyche is told she is going to marry an evil, serpent-like creature. She dutifully obeys, but her new husband doesn’t allow her to look at him.

Psyche eventually falls in love despite being unable to see who she’s in love with. Ultimately, it turns out that her husband is the god Cupid.

Much like Belle in Beauty and the Beast, Psyche falls in love with what appears to be a monster and ends up with a beautiful man.

Pedro’s wife Catherine, on the other hand, was with her husband for 40 years and never got to witness any stunning transformation. In some ways, that makes the story of Pedro and Catherine even more magical than the Disney version.

If you enjoyed learning the origins of Beauty and the Beast, read more about the twisted origins of Hansel and Gretel or the historical context behind the Pied Piper

Sources

Carrasco, Enrique. Gonsalvus, Mi Vida Entre Lobos. Ediciones IDEA, 2006.

Cox, Carolyn. “Petrus Gonsalvus: The Real-Life Tale behind ‘Beauty and the Beast.'” Theportalist.com, 9 Sept. 2016, https://theportalist.com/petrus-gonsalvus-the-real-life-beauty-and-the-beast.

Jessen, A. Die Schöne und das Biest. Heilberufe 74, 66 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00058-022-2247-9

Quartapelle, Alberto. “La Verdadera Historia De Don Pedro González, El «Hombre Salvaje» De Tenerife Que Llegó a Ser Profesor De La Sorbona De París.” Revista De Historia Canaria, no. 203, 2021, pp. 295–311., https://doi.org/10.25145/j.histcan.2021.203.11.

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry. “The Wild and Hairy González Family.” Apparence(s), no. 5, 2014, https://doi.org/10.4000/apparences.1283.