Last updated on January 25th, 2023 at 12:12 am

Tattoos have had a fraught and complex history around the globe. What was once an important sacred and cultural form of expression quickly became stigmatized by the advent of modernism and colonialism.

No one country can lay a claim to inventing the art form. Ancient Greek pottery depicts tattooed Thracians, and a 5,300-year-old mummified body decorated with 61 tattoos was discovered in the mountains of Italy. Known colloquially as “Ötzi the Iceman,” due to his body being discovered inside a glacier, he is the oldest concrete evidence of tattoos.

Mummies and remains have been discovered in 49 other locations, including Alaska, Mongolia, Greenland, Egypt, China, Sudan, Russia, and the Philippines.

In the 1400s, however, tattoos became a way to demark European colonizers from “savage” indigenous peoples. Today, both the appeal and the stigma of tattoos linger on, with celebrities ranging from the Rock to Rihanna using tattoos as a form of expression and society’s undesirables using them to demark gang affiliations or crimes, as in the case of the infamous “teardrop” tattoo common on murderers.

In Japan, the history of tattoos is both similar and unique. Much like in the rest of the world, it once held deep significance before becoming stigmatized as the world began modernizing.

In the late 1800s, Japan went a step further and banned tattooing across the nation. And while tattoos are frequently associated with criminal activity, this connection was even more pronounced in Japan – it was a method of punishing and permanently branding criminals.

Today, walk into any Japanese onsen (bathhouse), hotel, or gym, and you will likely come across signs banning the exposure of tattoos.

Due to their association with the Yakuza, the Japanese mafia infamous for their total-body tattoos, over 56% of all hotels and bathhouses refuse service to tattooed visitors.

The Difference Between Irezumi and Wabori

Irezumi is the Japanese word for tattooing, but the traditional Japanese tattoo style, which dates back over 5,000 years ago, is known as Wabori.

This bold and highly visual style is devoid of the ambiguity of, for instance, the pattern-based style of Alaska’s Indigenous Inupiat people.

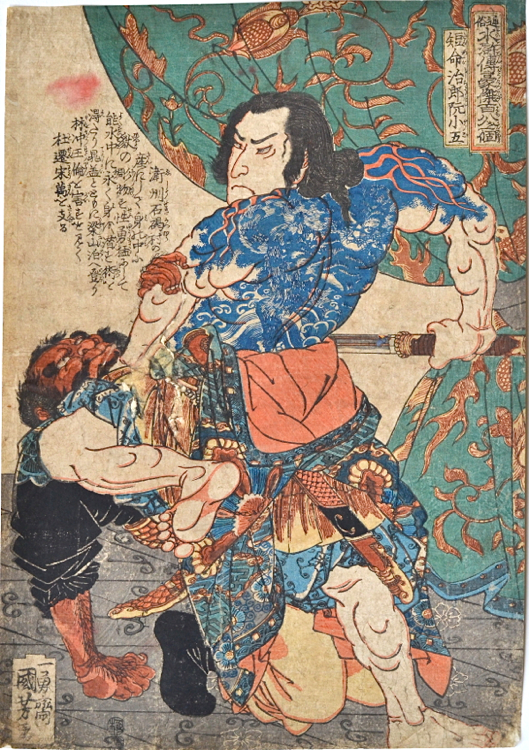

Instead, it typically features intricate pictorial tattoos that depict scenes of nature, war, mythology, and erotica taken from a genre of Japanese art called Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World).

The above scene, taken from the Ukiyo-e artist Kuniyoshi’s woodblock print series “108 Heroes of the Suikoden”, is one of the most popular scenes to create Wabori tattoos.

Other popular choices are actors in kabuki (Japanese theatres) or yokai, mythological creatures such as the Japanese dragon or the Oni, a red ogre-like demon you can find today on your emoji keyboard.

Samurais and the Men of Wa

In Ancient Japan, men often decorated their faces and bodies with tribally-specific designs and protection symbols. Some texts suggest that the samurai used tattoos to identify themselves on battlefields – the historical equivalent of modern-day dog tags.

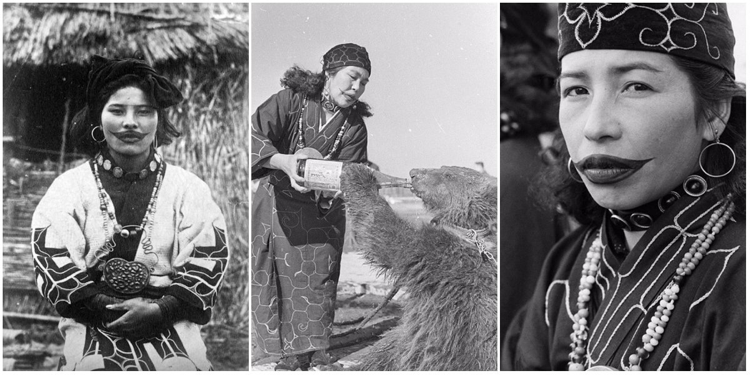

Other tattooing traditions existed among indigenous tribes, such as the Ainu, who lived in the Hokkaido region of Japan and used tattoos for cosmetic, religious, and social purposes. Interestingly, it was a predominantly female activity often used to demark sexual maturity.

But the Chinese, who referred to Japan as “Wa” and its inhabitants as “barbarians,” were strongly averse to body art. In Confucius’s doctrines, he claimed that “to preserve one’s body is to preserve god.”

In 1614, Japanese shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu used this statement to criticize the practice of Irezumi, which was in full swing across Japan.

An Elite Activity

Japan’s Edo Period (1603-1867) was the golden age of Irezumi. But during this period, the samurai elite enforced strict hierarchical control over the population, and one of the ways to enforce this was by prohibiting the lower classes from partaking in Irezumi.

Some of those who rebelled against the criminalization of Irezumi were regular citizens who used body art for spiritual protection and even expressions of love. In contrast, others made it a symbol of rebellion against the military dictatorship of the Tokugawa shogunate.

A new form of control was enforced when the ban proved unsuccessful: the policy of Bokkei. Under this policy, all criminals were to be branded with tattoos as punishment.

Petty criminals, courtesans, and members of the Yakuza were all branded to prevent their reintegration into respectable society. The symbols used would vary depending on the law enforcer’s crime, region, or impulse and would range from a simple line around the forearm to a “kanji” (Chinese character) on the forehead.

This branding policy endured for over 200 years, by which time Irezumi became a practice that was popular only among the Yakuza, who rebelled against Bokkei by decorating their bodies with Ukiyo-e tattoos that extended from their necks to their elbows and knees.

During the Meiji Restoration

Bokkei was eventually revoked and replaced with a national ban on tattoos in 1872. Following the decline of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Japan began to open itself to trade with the rest of the world (an event you may be familiar with through the entertaining yet not entirely historically accurate film “The Last Samurai”).

However, the country, which had been isolated for over 200 years, was lacking in modern technologies that its neighbors had long since adopted, such as steam power, telegraphs, and advanced military weaponry.

As part of its efforts to emphasize its modernism, the Japanese government severely prohibited Irezumi and all forms of tattooing. It disproportionately targeted marginalized communities, such as the Ainu, to homogenize the people into the Japanese empire. But the Yakuza, primarily consisting of a heavily discriminated group of people called the Burakumi, continued to practice Irezumi in secret.

World War II

With World War II came a surge in demand for tattoos, as even respectable citizens tattooed their bodies with Irezumi to seem undesirable to the armed forces and evade conscription. And following Japan’s surrender, thousands of western soldiers were deployed to Japan and became fascinated by the artistry and complexity of Irezumi.

The Meiji government exempted foreigners from the tattoo ban and begrudgingly permitted Irezumi artists to practice their craft in Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki to cater to their demands.

Eventually, in 1948, the prohibition against tattooing was lifted. In its place, the government instituted the Medical Practitioner’s Act, which forbade anyone other than a licensed doctor from performing “medical practices” – a term that the government deemed to include the inscription of tattoos.

The stigma, however, was preserved, especially with the advent of 1960s Yakuza films, which further connected Irezumi to gangster activity.

The Present Day

In 2014, an estimated 3,000 tattoo artists were working in Japan, compared to 200 in 1990. The stigma has gradually decreased as Irezumi declines in popularity among the Yakuza and becomes increasingly coveted by tourists, executives, celebrities, and creatives. In 2020, however, a 32-year-old man named Taiki was fined USD 1,400 for tattooing three clients.

But for the first time in history, the Japanese Supreme Court acknowledged tattooing as an art rather than a medical procedure, thereby legalizing tattooing for the first time in hundreds of years and honoring its status as one of Japan’s most incredible forms of artistic and cultural expression.

Sources

https://authoritytattoo.com/history-of-tattoos/

https://www.sapiens.org/biology/native-american-tattoos/

https://voyapon.com/horimono-history-traditional-tattoos-japan/

https://hypebeast.com/2020/9/supreme-court-of-japan-tattooing-now-legal-news