In the 1940s, the American television and film-making industries began experimenting with a psychological approach. It aimed to sell products where single-frame product endorsements were embedded in film. These were undetectable to the eye, but hopefully, acknowledged by the viewer’s brain.

One of the earliest examples of this technique was a 1943 cartoon short featuring Looney Tunes character Daffy Duck with the words, “Buy Bonds” appearing every 25 frames. It appeared for just a fraction of a second.

There was no way to prove that the rise in sales of US Savings Bonds that followed was a direct result of this “subliminal” advertising. However, the mere possibility that it had was incentive enough for the television and film-making industries to continue its use.

And while there is still much debate as to its effectiveness, this practice continues to this day.

Putting it to the Test

By 1957, virtually all films shown in theaters subliminally encouraged moviegoers to buy Coca-Cola and popcorn. According to statistics, they did.

To test the overall effectiveness of “subliminal” advertising, American marketing specialist James Vicary had several messages embedded in the 1955 film Picnic (starring William Holden, Kim Novak, Rosalind Russell, Susan Strasberg, and Cliff Robertson). This included the slogans “Drink Coca Cola” and “Hungry? Eat Popcorn.”

These images appeared every five seconds. Their exposure length was just under 50 milliseconds.

Test audiences who viewed advance copies of the film were informed of the embedded “subliminal” messages. They were instructed to consciously try to detect them. None could.

The experiment lasted six weeks. 45,000 movie-goers were exposed to the embedded version of the film. The results showed that while this experiment was taking place, popcorn sales rose by 57.5 %, and Coca-Cola sales by 18.1%.

To the academic community, these results were shocking. But to the film-making/advertising industry, they saw only dollar signs.

Media Push-Back

In the October 5, 1957 issue of The Saturday Review, Norman Cousins, the influential editor of the magazine, alerted readers of this phenomenon. He issued a scathing rebuke of the film/advertising alliance called, “Welcome to 1984.”

He was referring to the nightmarish dystopian society described by George Orwell in his novel 1984. In this, an omnipresent, totalitarian government engages in constant surveillance of its citizens. They persecute individuality and independent thought. Cousins warned readers of the ominous prospects of “subliminal” messaging.

Cousins noted that marketing specialist James Vicary was fully aware of the potentially dangerous uses of “subliminal” communication. They suggested that the public should be forewarned when subliminal messaging is in use.

They also suggested that some sort of governmental regulation should be considered. In short, Cousins denounced the flagrant use of subliminal advertising in no uncertain terms.

Early in 1958, Life magazine published an article in which they described the “hidden” selling techniques used in movies in basic layman’s terms: “Images that flash too quickly for the conscious mind to acknowledge but nonetheless unconsciously register in the brain.”

It went on to explain that several repetitions of “subliminal” messages could indeed affect a person’s behavior.

To illustrate their point, Life presented actual single-frame stills of what Vicary had embedded in the film Picnic: “Hungry? Eat Popcorn” appearing in one frame, then fading quickly in another.

Life addressed “subliminal” advertising as fact, then went on to discuss its potential ramifications. Not only in selling products, but in gaining support for issues such as anti-litter campaigns. Or perhaps even influencing citizen’s choice of political candidates.

Governmental Intervention

Even before the subliminal message-damning issue of Life hit the newsstands, Washington was being inundated with calls and letters from concerned citizens.

In late November of 1957, the trade publication Sponsor reported that a growing number of Congressmen were outraged by the idea of “subliminal” advertising. The Federal Trade Commission was investigating the technique.

The National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters was asking affiliates to report any use of subliminal techniques. At this time, virtually no one was aware that these techniques were already being used in television.

Despite having no proven cause-and-effect related to “subliminal” advertising, Congress introduced legislation that would ban subliminal communications. Some Congressmen felt that legislation against something that could not be seen or perceived was an overreach.

Although the proposed legislation failed to become law, public outrage and government concern continued. Wary of how the use of “subliminal” advertising would be received in light of public awareness, ad-men grew cautious and often balked at using the method.

In 1958, the Advertising Research Foundation issued a report titled, “The Application of Subliminal Perception in Advertising,” which concluded with the following statement:

“The available [psychological] experiments and observations on ‘subliminal perception’ seem to indicate that in certain instances human subjects are capable of responding to stimuli which are so weak in intensity, duration, size or clarity, that they are not consciously aware of them. The evidence is insufficient to draw any conclusions about the merits or even the possibility of subliminal advertising.”

Advertising Research Foundation

In 1957, the US Government was debating the legalities and potential effects of “subliminal” advertising (in all its conceivable applications). American journalist Vance Packard published what was at that time the definitive work on this phenomenon called, The Hidden Persuaders.

In it, Packard explains the many motivational techniques used in advertising and marketing. These were techniques that allowed advertisers and marketers to “delve more deeply into consumer psychology than what can be learned by asking people directly about their likes and dislikes.”

Packard discusses the practice of measuring pupil dilation to monitor pleasurable responses to TV commercials. He also discusses the concept of tracking changes in voice pitch to study positive or negative reactions to products.

There was also the practice of wiring theater seats with detectors to monitor fidgeting (and thereby chart levels of boredom). As well as measuring brainwave activity to assess the level of arousal created by ad imagery.

Physiological studies had been conducted years earlier to measure responses to external stimuli (sight and sound; as well as smell, taste, touch). But it was their specific application to marketing that concerned Packard.

His contention was straight to the point: “We are being monitored, managed, and manipulated outside our conscious awareness by advertisers and marketers.”

The Hidden Persuaders was well-researched and well-presented. He quoted several reliable research studies and chose provocative chapter headings like, “The Psycho-Seduction of Children,” “The Built-In Sexual Overtone,” and “New Frontiers for Recruiting Customers” to drive his point home.

In the wake of public outrage regarding the reported brainwashing techniques used in the Korean War, the very thought that such methods were being used on Americans–on American soil—was cause enough for public alarm.

Magnified by Packard’s revelations concerning the so-called “popcorn experiment,” Americans now had to think twice about something as basic as catching a Saturday matinee.

Back-Peddling

In 1962, Advertising Age magazine published a retrospective look at “subliminal” advertising called, “The TV Spot Heard Round the World,”

In it, reporter Fred Danzig noted the almost universal condemnation of subliminal advertising. He tracked down marketing specialist James Vicary.

Vicary is now a survey research director for Dun & Bradstreet, a company that specializes in commercial data, analytics, and insights for businesses. He then invited him to go on record about his involvement.

But rather than own-up, apologize, or use the opportunity to assuage public concerns, Vicary deflected his involvement. He claimed naivete and depicted himself as a victim of circumstances:

“You know, I first had the idea for subliminal many years ago, but I was ashamed of it. It struck me as a form of high jinks . . . I never regarded myself as a wheeler-and-dealer. But years later, there I was in my own business and the people who were putting up the money thought I should stir things up. They thought it was a good time to pull subliminal out of the drawer . . . So we worked out this apparatus to make subliminal advertising work . . . We applied for a patent, after testing the thing in a movie theater in Fort Lee, N. J. The story leaked out to some newspaper guys and we were forced to come out with subliminal before we were ready. Worse than the timing, though, was the fact that we hadn’t done any research, except what was needed for filing a patent.”

James Vicary

Vicary went on to say that what bothered him most was the public’s outrage at his idea. He’d been avoiding public appearances, unlisted his phone number, and for a time, feared for his life. He said he’d been trying to rehabilitate his image and didn’t want to forever be known as “Mr. Subliminal.”

New Evidence?

Despite the questionable effectiveness of “subliminal” messaging, many films made in the 1960s continued to utilize the method and scientific studies of the phenomenon persisted.

One such study involved flashing the words “Hershey’s Chocolate” on a series of slides during a student lecture to see if they would be influenced to purchase Hershey’s products during a 10-day period. There were no definitive results.

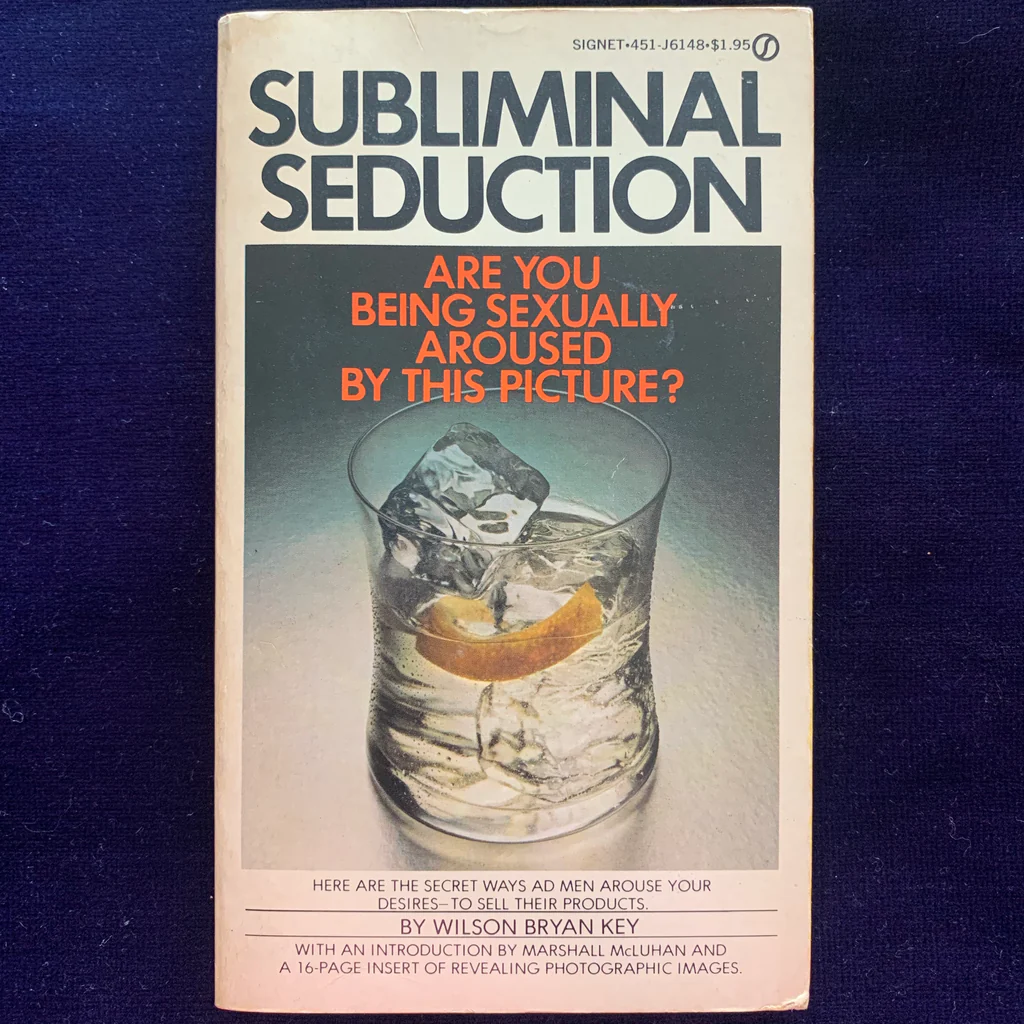

With interest fading, “subliminal” advertising may have run its course were it not for a college professor named Wilson Bryan Key. They provided new evidence in 1972 in a book titled Subliminal Seduction.

The paperback edition of Subliminal Seduction had what was one of the most provocative book covers ever to hit bookshelves. It featured a large, central photograph of a mixed drink—ice cubes, a clear liquid (such as vodka tonic), and a lemon twist—with a caption written in red letters asking, “Are You Being Sexually Aroused by this Picture?”

This was coming at the tail end of an era when sexually seductive paperbacks were in vogue (with titles such as “Sex-A-Rama,” “3-Way Lust,” and “Topless Waitress”). Many readers could not resist a scientific explanation of sexual arousal. Key’s book became an instant best-seller.

Subliminal Seduction reiteration claims were made by Packard and Vicary, along with new evidence he and his students had discovered. Key argued that print advertisers embed images of body parts (like breasts and genitals), wild animals, and other arousing images in their ads.

This was far more effective than simply flashing “Hungry? Eat Popcorn” in a film strip. These images become deeply embedded in our unconscious minds because of their seductive nature.

According to Key, “We are stimulated by them and ultimately motivated to purchase the advertised products and brands that use them.” As evidence of this trend, Key provides Gilbey’s Gin and Jantzen swimwear ads that have been sexualized.

The 1990s

Among the first social scientists to publicly take a position regarding the “subliminal” messaging issue were psychologists Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

In their 1992 book, Age of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion, the researchers conclude that subliminal messages do not appear to be able to affect subsequent human behavior. This includes decisions related to buying products.

Even so, the media continued to remind the public of the purported use of “subliminal” techniques by Pepsi Cola in 1990. The company had produced a new design for its “Cool Cans.” They had a trendy look intended to attract consumers during the summer.

But as someone discovered, when the cans were stacked in a particular manner, the letters S-E-X appeared. (This immediately vindicated Key’s assertion about the 1971 Gilbey’s ad.)

The New Millennium

By the year 2000, most filmmakers and advertisers were no longer attempting to hide “subliminal” messages in their movies and ad campaigns. Rather, they would challenge the public to spot the hidden messages (in film, billboards, print ads, and television).

In 2004, for example, subliminal advertising was used blatantly in the context of political advertising in a television ad for George W. Bush. This was the very thing Norman Cousins had warned about in the 1950s.

When the ad first appears on the screen, the letters R-A-T-S appear for a split second before the camera pulls back and the full word B-U-R-E-A-U-C-R-A-T-S manifests. When campaign officials were asked to comment, they made no attempt to deny it.

Similarly, director/producer Matt Reeves inserted multiple single frames from classic monster movies like King Kong, Them!, and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms in his 2008 film, Cloverfield—to see who could spot them.

Another example of hidden-in-plain-sight “subliminal” messaging is the Amazon logo, where the arrow goes from the A to the Z, a reference to Amazon selling a wide variety of products (from A to Z). On second look, the arrow forms a smile, which creates a positive, friendly association with the brand.

But not all “subliminal” messages are self-serving. Among those promoting a positive agenda is Honey Nut Cheerios’ removal of its mascot, “Buzz the Bee,” from its cereal boxes, leaving behind just a white outline of the famous bee.

Its intent was to bring attention to the dying bee population of the world. The marketing campaign hoped to indirectly encourage consumers to grow bee-friendly flowers by tying the important environmental cause into its product packaging.

The (Possibly Disturbing) Future of “Subliminal” Messaging

Modern technology has expanded the concept of “subliminal” messaging into several variations. These include:

- “Sub-visual Messaging” (used primarily in television, print, and visual ads)

- “Sub-audible Messaging” (used in song and recorded interviews)

- “Backmasking” (a technique using a voice played backward)

- “Supraliminal Messaging” – programs that not only target the subconscious but conscious mind (used to stimulate several areas of the brain simultaneously; the Amazon logo said to be one such example).

Today there are “subliminal” message apps to self-program the mind. There are AI-generated subliminal programs to create effective advertising strategies for home businesses. There are also subliminal motivational apps to help overcome addictions.

There are even programs available to therapists to help replace negative images with positive ones in the treatment of conditions such as PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). And that’s undoubtedly just the beginning.

Now that two generations of consumers have been raised on technological advances and invasive technology is the norm, we may very well welcome the very thing we once feared most.

References

ijcr.eu., “HISTORY OF THE 25TH FRAME. THE SUBLIMINAL MESSAGE,” http://ijcr.eu/articole/330_07%20Maria%20FLOREA.pdf

screenrant.com., “Shocking Subliminal Messages Hidden in Popular Movies,” https://screenrant.com/secret-movie-hidden-subliminal-messages/

ditext.com., The Hidden Persuaders, http://www.ditext.com/packard/persuaders.pdf

scientificamerican.com., “A Short History of the Rise, Fall and Rise of Subliminal Messaging,” https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-short-history-of-the-rise-fall-and-rise-of-subliminal-messaging/

archive.org., Subliminal Seduction, https://archive.org/details/wilsonbriankey.subliminalseduction

muse.jhu.edu., “Subliminal Advertising,” https://muse.jhu.edu/article/497057S

seodesignchicago.com., “Is Subliminal Advertising Used Today?” https://seodesignchicago.com/advertising-blog/is-subliminal-advertising-used/

sharethis.com., “9 Examples of Subliminal Advertising (and Why They Work),” https://sharethis.com/marketing/2023/02/examples-of-subliminal-advertising-and-why-they-work/

sharethis.com., “What is Subliminal Advertising (and Should You Leverage It for Your Brand)?” https://sharethis.com/marketing/2021/07/what-is-subliminal-advertising-and-should-you-leverage-it-for-your-brand/