The New Year celebrated in most parts of the world is January 1 of the Gregorian Calendar. While it doesn’t explicitly say that it’s the Christian New Year, the Gregorian Calendar was instituted by Pope Gregory XIII through a papal bull or edict in 1582.

However, different cultures and religions have different New Years:

- Chinese New Year

- Diwali – Hindu New Year

- Hijri – Islamic New Year

- Matariki – Maori New Year

- Nowruz – Persian New Year

- Songkran – Thai New Year

This article will focus on the Jewish New Year, known as Rosh HaShanah.

Definition of Terms

Before we proceed to the discussion of this celebration, let us first define some terms that will notably be mentioned in the article.

- Akedah – the Genesis story on the Binding of Isaac.

- Days of Awe – 10-day Jewish celebration that starts with Rosh HaShanah and ends with Yom Kippur. The Jews believe that these are the days that God judges people.

- Selichot – special penitential Hebrew prayers.

- Shofar – is a hollowed-out ram’s horn blown during the Rosh HaShanah prayers.

- Tishrei – is the first month in the Hebrew calendar.

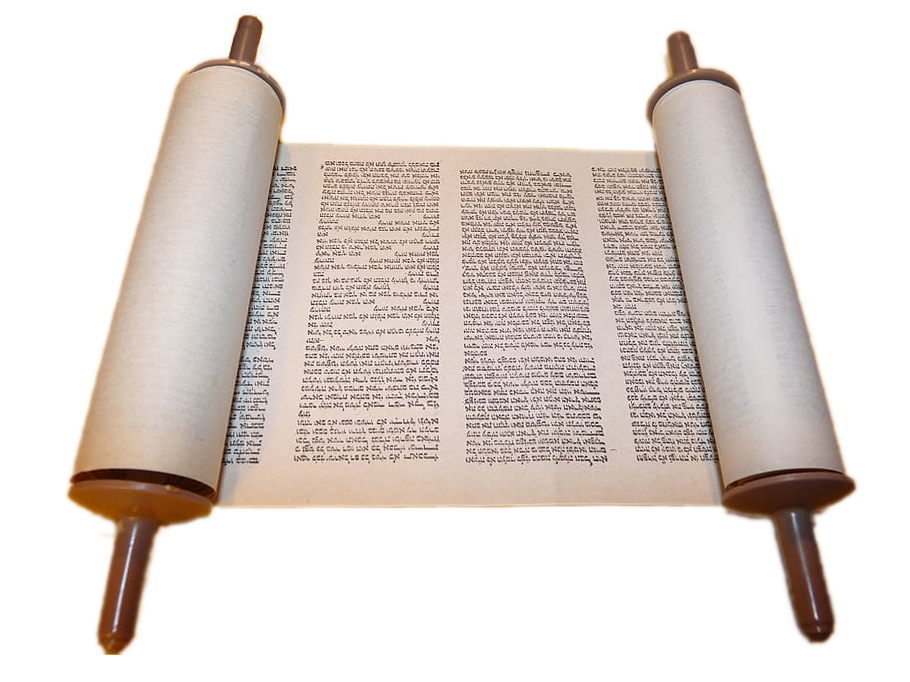

- Torah – a compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

- Yom Teruah – is the term for Rosh HaShanah in the Hebrew Bible.

- Yom Kippur – is considered the holiest day of the year in Judaism.

The History of Rosh HaShanah

Just like most New Year celebrations, the Jewish community gets together on Rosh HaShanah to reflect on the year that was and how they look forward to a more prosperous year.

But what is the history of Rosh HaShanah?

The celebration’s beginnings were tied to the agricultural practices of the Ancient Near East, which evolved into the modern Middle East. The early Jews considered the beginning of the agricultural cycle – sowing, growing, and harvesting crops – as the start of the year.

Rosh HaShanah literally means “head of the year” as Rosh is Hebrew for “head,” Ha is the article “the,” and Shanah means “year.”

Rosh HaShanah also commemorates the world’s creation. In terms of the celebration, it also gives a start to the 10-day introspection that culminates in Yom Kippur. Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur are considered the High Holy Days for the Jews.

The Jews actually celebrate four New Years, with Rosh HaShanah as the first of Tishrei, or the Hebrew calendar month. The next New Year is the Nisan, the start of the Exodus, or the time the Israelites left Egypt. The year also represents many bible events, such as the first day the flood waters dissipated in the story of Noah’s Ark.

Another New Year is the first of Elul, or the harvest month. Finally, there is Tu BiShvat, or the New Year of the Trees.

Each New Year celebrates the start of a calendar year pertaining to a season.

Yom Teruah

The term Rosh HaShanah doesn’t appear in the Hebrew Bible. Instead, Yom Teruah, or the day of blowing trumpets, appears. However, the Jewish people believe that Rosh HaShanah started during the 6th century Before the Common Era.

It wasn’t until Year 200 that Jewish texts mention Rosh HaShanah.

How Rosh HaShanah is Celebrated

Unlike the Gregorian calendar that celebrates the New Year every January 1, the Rosh HaShanah date changes every year. It is similar to the Chinese New Year and Diwali, which vary every year based on their respective lunar calendars.

Rosh HaShanah is celebrated every first day of the seventh month of the Hebrew Calendar. In the Gregorian Calendar, it usually falls in September and October.

It may be called another name, but the celebration resembles the widely celebrated New Year. The Jews would reflect on what happened in the past year, repent their wrongdoings, and pray for a better year ahead.

The synagogues are always filled to the brim during these days as most of the Jewish people take off work to observe the annual religious tradition. Expecting a deluge of congregants, Rosh HaShanah or Yom Kippur is usually held in college auditoriums or hotel ballrooms. In Israel and Ukraine, Rosh HaShanah is a holiday.

Many also observe two days of Rosh HaShanah.

Preparation

Jewish people celebrate Days of Awe in both the home and the synagogue. Weeks before Rosh HaShanah, which marks the start of the Days of Awe, Selichot is recited in the synagogue.

The Selichot is usually done on a Saturday a week or two before Rosh HaShanah. The solemn tradition is fulfilled by candlelight, which heightens its solemnity.

Shofar

There are many traditions in Rosh HaShanah. One of the most popular is the blowing of the shofar, one of the world’s oldest winged instruments.

It is an iconic Jewish tradition with deep meaning, as the curve of the shofar symbolizes a person’s humility in front of god. The shofar is blown throughout the Days of Awe.

There are four variations of the shofar blowing:

- T’kiah – one long blast

- Sh’varim – three short blasts

- T’ruah – nine quick blasts

- T’kiah g’dolah – one very long blast

They represent the different “sounds” of people’s everyday lives. They are noted wake-up calls for people to repent and start the new year afresh.

Family Gatherings

People usually gather for Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur. Families have dinner together before they head to the synagogue for service. The following are some of the most important food items served during dinner:

- Apples dipped in honey – to symbolize the hope for a sweet year ahead

- Carrots – in Yiddish, the carrot is called ma’rin, which literally translates to increase. Eating carrots, in Jewish tradition, means increasing one’s blessings. Plus, slicing carrots will make them look like coins, and that represents prosperity and wealth. In Hebrew, carrot is gezer, which sounds like g’zar, which means decree. Eating carrots is explained as nullifying any negative decrees.

- Pomegranates – as each fruit contains a lot of seeds, Jewish people eat it to wish for a year filled with good deeds. Pomegranates are usually eaten before the family celebration.

- Round challah – typically, challah is oval, but for Rosh HaShanah, the Jews eat the round one to symbolize the continuity of life and seasons. The round shape is also a reminder that when people sin, repentance is always available. Moreover, the round challah resembles a crown that the Jews believe symbolizes God’s sovereignty.

- Yehi Ratzon platter – many don’t really eat a lot of apples dipped in honey or pomegranates as the Rosh HaShanah celebration is a whole feast. So, most Jewish households will prepare the Yehi Ratzon platter that already contains all the traditional New Year food items, such as honeyed apples, pomegranates, dates, black-eyed peas, beets, rondanchas or pumpkin-filled pastries, and keftedes de prasa or leek fritters.

Torah

Every Church service, whatever the denomination, always involves reading the bible. In the case of the Jews, their bible is called the Torah. During Rosh HaShanah, the Torah is read, and one of the most famous selections is Genesis 22:1-19 or the story of the Binding of Isaac.

Why is the Akedah an important story in the Jewish celebration? The story, which is also in the Catholic Bible, narrates how God basically compelled Abraham to bind his son and offer him as a sacrifice to God.

Many fathers may not have heeded God’s directions, but Abraham trusted him implicitly. The story shares the importance of God’s oath.

The same story also had Abraham sacrificing a ram for God, which is also where the shofar tradition started. The ram was sacrificed in place of Isaac when God finally told Abraham He was just testing him.

There are other Torah readings, too, particularly when Jewish people celebrate Rosh Hashanah for two days.

Tashlich

On the first afternoon of Rosh HaShanah, many Jews gather around a large body of water for the tradition known as Tashlich. The activity is recommended for Jewish children between three and five years old, but anyone can join the Tashlich if they wish. After all, the activity signifies the washing of one’s sins.

People who observe the Tashlich also have small pieces of bread in their pockets that they throw into the water as a way of casting their sins into the sea. Some also throw stones or wood chips as bread isn’t good for any of the wildlife that might eat it.

Shanah Tovah

Jews greet each other with “Shanah Tovah” every Rosh HaShanah, which means “Have a good year.” Sometimes, people add Umetukah at the end to mean, “Have a good and sweet year.” There are other variations, too, but the point is to greet each to have a positively better year ahead.

During Yom Kippur, the greeting turns to Gmar Tov or “A good conclusion.”

Rosh HaShanah Today

Perhaps today, more than ever, Rosh HaShanah has become more important to the Jewish community.

“Think about the ways that we want to create a safe community, a welcoming community, a warm community and then be able to enrich the world around us after having those moments of introspection,” Penn State Hillel reform senior Jewish educator Peter J. Rubinstein said of the most recent Rosh HaShanah celebration.

While not generally considered a holiday throughout the world, many employers recognize the celebration and allow Jews to take off work for the festivities and days of repentance.