Sometimes a person appears who decidedly upends entire systems of thought. They encourage others to reconsider what they thought they knew.

Bobbi Gibb is one of those people. She dedicated over 50 years of her life to battling misogyny in sports and shifting the perception that women are less physically capable than men when it comes to competitive athletics.

Falling in Love with Running

Roberta ‘Bobbi’ Gibb grew up in the suburbs of Boston during the affluent postwar years of 1950s America. She was always painfully aware of the reality of women’s lives in these years.

She watched her mother drink and take tranquilizers with her friends. A coping mechanism used to tolerate the monotony of remaining a stay-at-home mother and wife rather than pursuing her own dreams.

She understood that society saw women as frail and incapable of nearly anything except producing children. From a young age, Gibb was determined to avoid living a similar life. She sought to prove that women were capable of more by pursuing her dreams at any cost.

Gibb spent her childhood running around outdoors, exploring nature in her local neighborhood. She was filled with a sense of adventure and awe for the world. She developed a love of running at an early age.

Despite her love of running and growing up near Boston, she did not attend the Boston Marathon until 1964. But once she did, the effect it had on her was profound. She immediately felt a sense of community with the runners and sought to join their ranks.

That summer, she took a road trip across the United States in her parent’s Volkswagen van. She stopped to admire various national parks and natural wonders. She ran up to 40 miles daily, usually in nurse shoes because they were the closest thing to a running shoe available to women then.

She moved to San Diego but continued training. She started preparing for the day she would return to Boston and take on the marathon.

“Not Physiologically Able”

Gibb applied to participate in the 1996 marathon, after two years of training on her own. In February of 1966, she received a response back from the organizers of the race. They denied her application.

The letter stated that women were “not physiologically able to run a marathon.” The letter cited the Amateur Athletics Union’s rule that women were not allowed to run in races over 1.5 miles.

The organization did not want to take on the liability of allowing a woman to run in the marathon. Thus, they denied her application. But Gibb was not going to give up on her dream that easily. In fact, the denial would inspire her even more.

In the days leading up to the race, Gibb formulated a plan.

She rode a series of Greyhound buses across the country to her parents’ house in Boston. She decided that she was going to run the marathon whether she was allowed or not.

Unlike other racers, she did not have a trainer or nutritionist to help her prepare her body. She even gorged herself the night before the race (which she later admitted made her stomach hurt after the race).

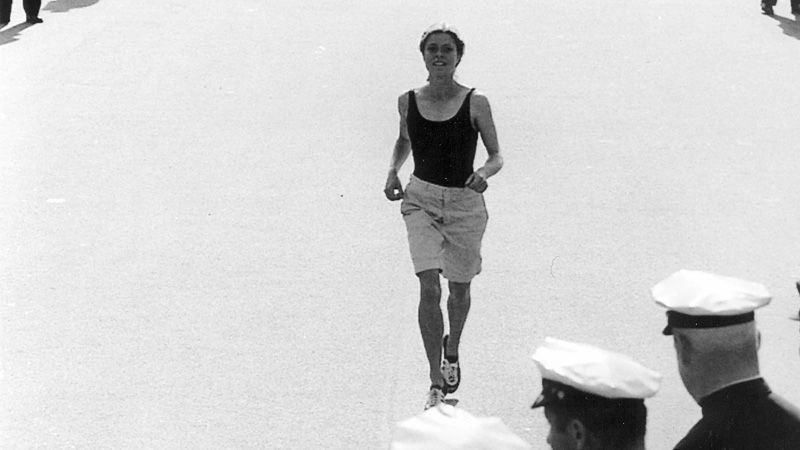

On April 19, 1966, her mom dropped her off near the starting line. Gibb hid in some bushes wearing her brother’s hoodie and shorts over a swimsuit to disguise herself. Shortly after the race began, she emerged.

She began running alongside the crowd of men, doing her best to blend into the runners around her.

Definitely Physiologically Able

There were many things about the plan that terrified Gibb. One fear was that upon discovery, she would be quickly removed from the race by officials who sought to maintain the integrity of the event.

More directly, she feared that the men in the race would be hostile towards her attempt to run alongside them. That fear came to a head quickly. The other runners figured out she was a woman by probably, as she says, “studying my anatomy from the rear.”

But the fear of hostility quickly evaporated when all of the men in the race began encouraging Gibb. A sense of camaraderie developed between her and the other racers. They were all there to enjoy the sport, not enforce gender stereotypes.

She quickly took off the hoodie to avoid overheating. She soon realized she was running to the sound of cheers, from participants and onlookers alike.

Along the path was Wellesley College, an all-women’s school. Word had reached the crowd there that a woman was running in the marathon. As Gibb approached, the crowd roared in support. This reinvigorated her. Her new running shoes were beginning to cut into her feet and the toll of the long race set in.

It would not be much longer before Gibb finished the race in an impressive three hours, twenty minutes, and forty seconds. This was a faster time than two-thirds of her male competition.

Waiting at the finish line were not officials ready to remove her from the race, but the governor of Massachusetts who welcomed her with a handshake and invited her to talk to the press about her historic feat.

Yet when it came time to celebrate with the traditional post-race stew, Gibb was denied access. The only reason was a firm “men only” presented to her at the door.

Reshaping Racing

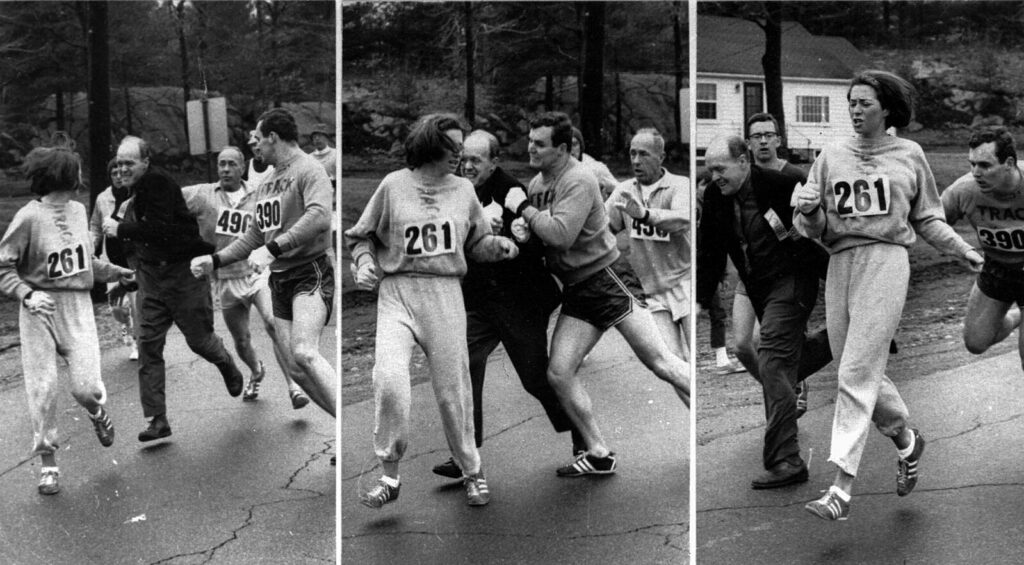

Gibb would go on to complete the marathon unofficially for the next two years. In 1967, she was joined by another woman named Kathrine Switzer.

Switzer had officially signed up for the race by lying about her gender on her application. She used only her initials and had her coach pick up her number.

A famous picture of the co-director of the race trying to wrest the number from Switzer during the race has led Switzer to gain credit for being the first woman to compete in the Boston Marathon. When the picture hit the news, the narrative of confrontation and sexism Switzer faced attracted national attention.

It aligned with the broader social reform of the period. Gibb’s story was lost in the fray because the racers, and even the directors, had welcomed her with open arms. Gibb hypothesizes that the only reason Switzer faced backlash at all was that the marathon could have lost its accreditation for “officially” having a woman racing.

Gibb then competed again in 1968 with even more women unofficially joining. It would not be until 1972 that the AAU rule was lifted and women were allowed to participate in races longer than 1.5 miles.

Nine women would compete in the marathon that year, with a growing number joining the race every year after. By 2017, women would consist of nearly half of all the racers.

Gibb had started a tidal wave of change by refusing to take no for an answer. Still, it would be over twenty more years before Gibb was officially recognized for her accomplishments.

In 1996, the Boston Athletic Association awarded Gibb a medal for her wins in 66-68. Her name was carved into the Boston Marathon memorial with other winners. The years before women were allowed to race became known as the “pioneer years” with Gibb as the face of change.

Closing the Athletic Gender Gap

The question of women’s physical ability to participate in sports is still debated. But proof continues to emerge that women are just as capable as men.

The gap between the fastest male and female marathon completion time is less than 15 minutes. In the last sixty years, the fastest women’s time for a marathon has dropped nearly an hour and a half. While in twice that time, men’s times have only changed by about an hour.

Women also continue to outperform men in other forms of endurance sports, including cycling and swimming. Leveling the playing field and encouraging women to participate in these sports has disproven innate perceptions that women are unable to compete.

As for Bobbi, running was not the only place she faced sexist restrictions. She finished premedical school but was denied the ability to become a doctor because she was a woman. Instead, she would go on to become a lawyer who practiced intellectual property law and now pursues her passion for art.

She has made multiple trophies for race wins over the years. There is even a sculpture of herself running that was erected at the Hopkinton Center for the Arts, near where the Boston Marathon begins.

Gibb continues to be an inspiration. She embodies the hope and dignity that she demonstrated over 50 years ago in Boston.

References

Ruhalter, Kana and Arun Rath. “Over 60 years later, Boston Marathon runner Bobbi Gibb wants us to celebrate life.” WGBH, April 14, 2023. https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2023-04-14/over-60-years-later-boston-marathon-runner-bobbi-gibb-wants-us-to-celebrate-life.

Guiberteau, Olivier. “Bobbi Gibb: The Boston Marathon pioneer who raced a lie.”

BBC Sport, August 28, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/sport/athletics/66615089.

Ross, Ailsa. “The Woman Who Crashed the Boston Marathon.” JSTOR, March 18, 2018. https://daily.jstor.org/the-woman-who-crashed-the-boston-marathon/.