‘Ain Ghazal houses the remains of an ancient culture that thrived there for thousands of years. It is one of the largest Neolithic settlements ever found.

The site is in modern-day Jordan and is best known for the ʿAin Ghazal statues that were discovered there in the 1980s. Some of the archeological remains found at ‘Ain Ghazal, or ‘Spring of the Gazelle’, are over twelve thousand years old.

The Fertile Crescent

‘Ain Ghazal was a part of the Fertile Crescent. It was that curved region in the Middle East where humans first began to practice agriculture.

Further advances to arise in that region include wheels, irrigation, writing systems, and glass. But each of those developments came after the preliterate civilization whose remains were found at ‘Ain Ghazal.

This region was rich in rivers and marshlands that provided the rich soil required for the development of agriculture. It also held greater biodiversity than other areas, both because of its many microclimates and because it was a bridge between continents.

The Fertile Crescent was home to the ancestors of modern goats, cows, pigs, geese, and sheep. It was also home to wild plants that were used to create modern crops such as wheat, barley, pea, chickpea, lentil, and flax.

‘Ain Ghazal began as a small neolithic settlement. It may have been home to a culture of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers called the Natufians, which began around fifteen thousand years ago.

The earliest evidence of deliberate cereal cultivation ever found can be traced back to the Natufian civilization. The same goes for humanity’s first bread and beer.

Natufians also had dogs. Dogs were so important to them that they were sometimes buried together with humans over fourteen thousand years ago.

Earliest Civilizations

The earliest evidence of civilization at ‘Ain Ghazal dates back to 8,300 BC. At this time, the region was home to small bands of hunter-gatherers.

The settlement was built on terraced ground above the Zarqa River, which is the second-largest tributary of the Jordan River. This location gave early settlers a view of the surrounding area, which was wooded on one side and open steppe on the other.

Villagers built rectangular homes out of mud brick covered in lime plaster. They began to cultivate grains and legumes, which allowed them to stay in one place. They also kept goats, while continuing to hunt wild cattle.

Over time, their population grew from two hundred settlers to over one thousand villagers.

Archeologists believe that there was a strong class hierarchy by this point. Some people were interned beneath their houses when they died, while many others were thrown into the local trash pit.

This drastic division between classes may have begun when a group of people from the east migrated west. They joined the original Natufian culture at this site.

Often, after a person had been buried for a time, they were disinterred and the skull was removed. The lower jaw and the rest of the skeleton were left behind.

This practice was likely a part of rituals revolving around the practice of ancestor worship. As with other Natufian peoples, the people of ‘Ain Ghazal sometimes used plaster to recreate faces over the skulls.

By 7000 BC, ‘Ain Ghazal housed a thriving metropolis of three thousand people. This remained steady for centuries before dropping off sharply after 6500 BC. This was probably due to a global cooling event that caused extreme and long-lasting droughts.

Even so, people continued to reside there for another two thousand years.

The Discovery of ‘Ain Ghazal

This archeological site was discovered in 1974 during the construction of a new road. The road continued on through, and excavation didn’t begin in earnest until 1982.

It remained an active archaeological site until 1989. Another set of excavations was carried out a few years later.

Nearly two hundred statues and figurines have been discovered at ‘Ain Ghazal. Many of these depict horned animals, mostly cattle, and others depict humans. They were made during the height of the civilization situated there, between 7200 BC and 6250 BC.

Many statues were destroyed by construction work, and others deteriorated quickly as soon as they were exposed to the elements. The latter excavation in 1985 exercised more care, block lifting them still interned and excavating them in laboratories to preserve the delicate plaster.

Art and Culture

There is evidence that the ceramic figures of ‘Ain Ghazal were used for ceremonial purposes. Some of the animal figurines were stabbed and buried beneath homes. Others were burned.

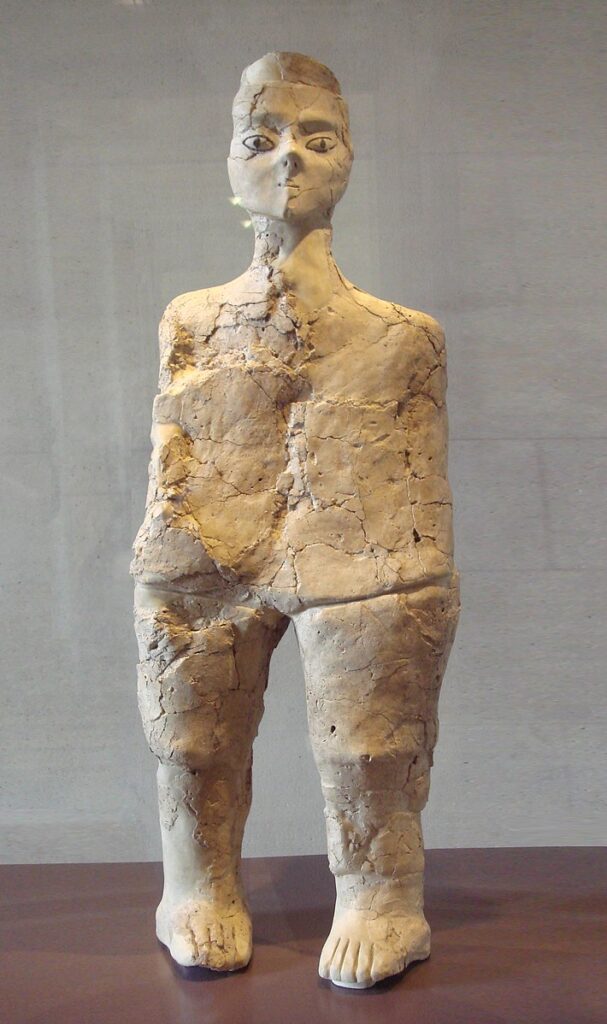

Some of the larger anthropomorphic statues were housed in ritual buildings. Others were buried in pits. Although the statues were capable of standing without support and often did for a short time, they were buried in pristine condition, suggesting that they were crafted for that purpose.

Two underground caches were discovered to have been created anywhere from a few years to two centuries apart from one another. They contained a total of fifteen statues and fifteen busts representing men, women, and children.

Three of the busts have two heads each. All of the two-headed statues were found in the second cache, which had only six in total.

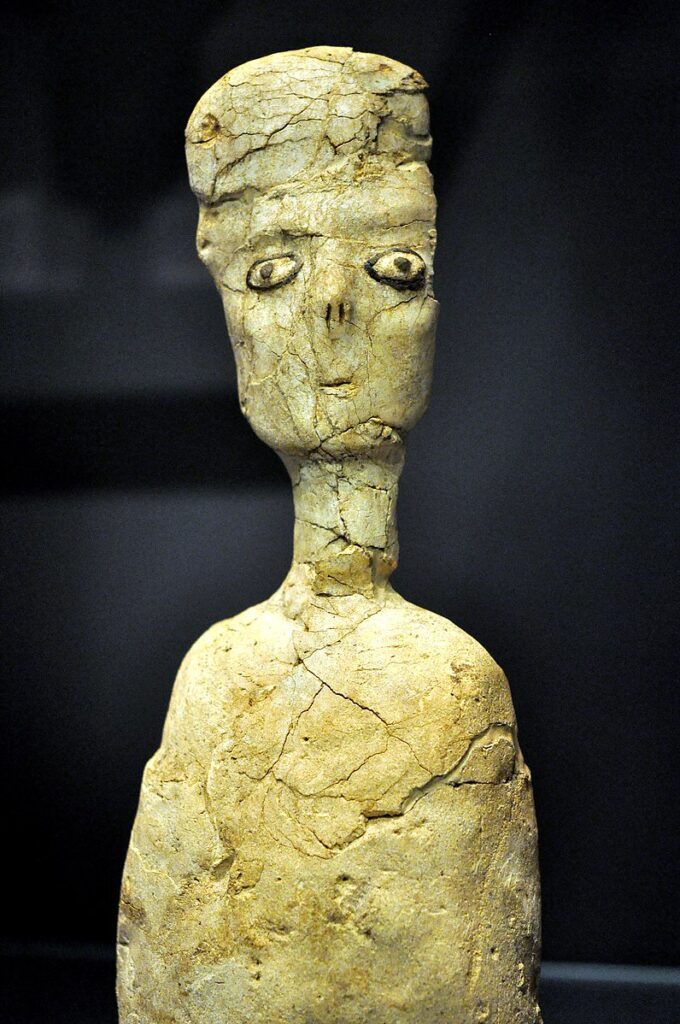

The bodies were not sculpted in detail. The arms are undersized, but a great deal of attention went into the heads, especially the oversized white chalk eyes.

The eyes of the later statues are especially large and almond-shaped. Black bitumen was used to draw large pupils and outline the eyes.

The heads were probably topped with some sort of wig that has long since rotted away, as have the cores of each statue. Many of the mouths curve upwards in gentle smiles.

These three-foot-tall statues were made of white plaster around a core of reeds. They were painted to represent hair, clothes, tattoos, and/or ornamental body paint.

Statues found in the older cache are more unique, while those created two hundred years later are more homogenous. Archeologists hypothesize that the early statues represented specific people, while the later ones from the much smaller cache may have had a more generalized purpose.