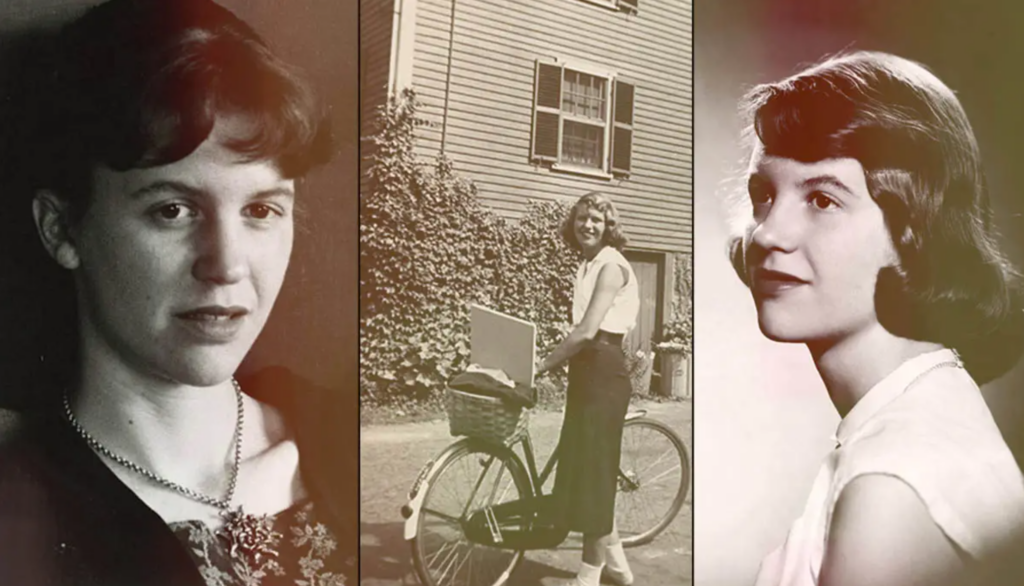

Credited with single-handedly advancing the genre of “confessional” poetry, Sylvia Plath is considered one of the most dynamic and admired poets of the 20th Century.

She is best known for her two highly acclaimed collections, The Colossus and Other Poems (published in 1960) and Ariel (in 1965). As well as her beautifully introspective semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar. Plath’s writing is a direct reflection of the demons she fought to overcome.

By the time she took her life at the age of 30, Plath already had a fervent following in the literary community. In the ensuing years, her work attracted a multitude of readers who saw in her verse an attempt to chronicle extreme emotions most writers consider too personal: despair, violence, and obsession with death.

In a New York Times book review, Plath contemporary Joyce Carol Oates described Plath as “one of the most celebrated and controversial of postwar poets writing in English.” Few who know her work would disagree.

The Beginning

Sylvia Plath was born on October 27, 1932, in Boston, Massachusetts to Otto Emile and Aurelia Schober Plath.

Her father was a German-born entomologist and professor of biology at Boston University of some renown. Her mother was a second-generation American of Austrian descent who taught high school German and English.

On April 27, 1935, when Plath was two and a half years of age, her brother Warren was born. The following year the family moved to Winthrop, Massachusetts. This was near where Plath’s mother and grandparents had lived in a section called Point Shirley since 1920. This was a location mentioned often in Plath’s poetry.

Tragedy Strikes

On November 5, 1940, nine days after Plath’s eighth birthday, her father Otto died of complications following the amputation of a gangrenous foot caused by untreated diabetes. Otto died believing he had lung cancer and not diabetes.

Plath was raised Unitarian. She experienced a severe loss of faith after her father’s death. She remained ambivalent about religion throughout her life. A visit to her father’s grave in Winthrop Cemetery sometime later prompted Plath to write the poignant poem, “Electra on Azalea Path.”

In 1962, the BBC Home Service commissioned Plath to write a short piece for their program, “Writers on Themselves,” in which novelists and poets discussed their early experiences and influences. Reflecting on her childhood in the US, Plath’s contribution was a poem called, “Ocean 1212-W” in which she refers to her first nine years of life as “sealed themselves off like a ship in a bottle—beautiful, inaccessible, obsolete, a fine, white flying myth.”

An Impressive Child

While living in Winthrop, the eight-year-old Plath had her first poem published in the Boston Herald’s children’s section. Over the next few years, several regional magazines and newspapers would also publish her writing.

In addition to writing prose and poetry, Plath also showed a remarkable aptitude for art. She won an award for her paintings from the prestigious Scholastic Art & Writing Awards in 1947.

According to those who knew her, even in her youth, Plath was driven to succeed (and said to have had an IQ of nearly 160).

Early Education and Recognition

In 1942, Aurelia moved her children and parents to Wellesley, Massachusetts. There, Plath attended Bradford Senior High School (now Wellesley High School) in Wellesley. She excelled as a straight “A” student, graduating in 1950.

Just after graduation, Plath got her first national publication in the Christian Science Monitor. It was a piece she described as “my little 3-page descriptive article about the countryside.” Soon after, she sold her first short story to Seventeen magazine. This was followed by one of her poems being accepted for The Sewanee Review.

In 1950, Plath enrolled at Smith College, a private women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts. While there she lived in the prestigious Lawrence House (named for Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence, who graduated from Smith in 1883). Immediately recognized for her writing genius, she was chosen as editor of The Smith Review.

In 1952, after her third year, Plath was awarded a coveted position as guest editor at Mademoiselle magazine after winning their annual fiction contest, spending a month in New York City. The experience, however, was not what she had hoped for. Many of the events that took place inspired her novel, The Bell Jar.

Dylan Thomas, Disappointment, Depression

While a guest editor at Mademoiselle, Plath experienced an incident that would trigger disappointment and depression that would plague her for the remainder of her life.

She discovered that she had not been included in a meeting arranged by her editor with the famous Welsh poet, Dylan Thomas (a writer whom she is said to have loved more than life itself).

She became so obsessed with meeting her idol that she spent two days camped outside the famed White Horse Tavern and Hotel Chelsea in Manhattan. These two spots were known for the Bohemian Culture they attract, including Thomas, Jim Morrison, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, and Jack Kerouac. She was unaware that Thomas had already returned to Wales.

A few weeks later, Plath slashed her legs to see if she “had enough courage to kill herself.” Shortly after, she was rejected for a Harvard writing seminar with famed Irish author Frank O’Connor—which deepened her depression.

Suicide and Therapy

After being sent for electroconvulsive therapy for depression, Plath made her first medically- documented suicide attempt on August 24, 1953, at the age of twenty-two.

She crawled under the front porch and took a bottle of her mother’s sleeping pills. She survived this first attempt. But she would later write that she “blissfully succumbed to the whirling blackness that I honestly believed was eternal oblivion.”

Consequently, she was committed to McLean Psychiatric Hospital (where she spent the next six months). She received more electric and insulin shock therapy under the care of psychiatrist, theologian, and Episcopal priest, Ruth Beuscher. This was a woman with whom Plath would maintain a relationship till the end of her life.

Interestingly, Plath’s stay at McLean Hospital—as well as her Smith Scholarship–was paid for by famed novelist and poet, Olive Higgins Prouty. Olive had successfully recovered from a mental breakdown herself.

Higher Education

In January of 1955, she appeared to have made a complete recovery. Plath then submitted her thesis, The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoyevsky’s Novels, to complete the requirements of Special Honors in English.

She graduated from Smith in June with an A.B. (bachelor’s degree), summa cum laude, and member of the Phi Beta Kappa academic honor society.

She received a Fulbright Scholarship to study at Newnham College (one of two women-only colleges of the University of Cambridge, England). Plath continued to write poetry, having her work regularly published in the student newspaper, Varsity. While at Newnham she studied with Israeli professor of English literature Dorothea Krook, whom she held in high regard.

Marriage, Career, Relapse

On February 25, 1956, Plath met English poet Ted Hughes (whose work she greatly admired). Less than four months later, on June 16, 1956, the couple married in London. Plath’s mother attended the wedding.

After spending their honeymoon in Paris and Benidorm (on the Mediterranean coast of Spain), Plath returned to Newnham in October to begin her second year. In June 1957, Plath and Hughes moved to the US. And beginning that September, Plath took a teaching position at Smith College.

She found it difficult, however, to teach and write. A problem was remedied when the couple moved to Boston in mid-1958. There, Plath took a job as a receptionist in the psychiatric unit of Massachusetts General Hospital.

To compensate for her feelings of estrangement from artistic expression, in the evenings she sat in on creative writing seminars held by poet Robert Lowell. These seminars also attracted poets Anne Sexton and George Starbuck.

Upon meeting, both Lowell and Sexton encouraged Plath to write from personal experience. She openly discussed her depression with Lowell and her suicide attempts with Sexton, who urged her to write from a more female perspective.

Subsequently, Plath began to consider herself a more serious, focused poet and short story writer. During this time, she was also befriended by author, poet, and playwright W. S. Merwin.

In December of that year, Plath resumed psychoanalytic treatment with Ruth Beuscher. Her depression was worsening.

Return to London

In 1959, Plath and Hughes traveled across Canada and the US. They stayed at the Yaddo artist colony in Saratoga Springs, New York. Plath wrote that it was there that she learned “to be true to my own weirdnesses.”

But she still remained anxious about writing confessionally; from her deeply personal and private recesses. Late that year, the couple moved back to England. They rented a flat in London—never to return to the US.

On April 1, 1960, their daughter Frieda was born. And six months later, Plath’s first collection of poetry, The Colossus, was published. Which seems to have ignited the need for further confessional introspection.

In February of 1961, Plath’s second (secret) pregnancy ended in miscarriage. Several of her poems, including “Parliament Hill Fields,” deal with this traumatic event. In a letter to Ruth Beuscher, Plath wrote that Hughes beat her two days before the miscarriage; behavior now thought to have been rooted in guilt from infidelity.

In August, Plath finished her semi-autobiographical, The Bell Jar, in which she describes the mental breakdown and eventual recovery of a young college girl. This book parallels Plath’s own breakdown and hospitalization in 1953.

Soon after, the couple moved to the small town of North Tawton in Devon, England. In January 1962, the couple’s son, Nicholas Farrar Hughes, was born.

Teetering on the Edge

In August of 1961, Plath and Hughes sublet their London flat to David and Assia Wevill. Plath immediately recognized the chemistry between Assia and her husband; a chemistry they would act on beginning in July of 1962.

A month prior, however, Plath crashed her car in an attempt to commit suicide. By September, Plath and Hughes had separated.

In October of 1962, Plath experienced a great burst of creativity and wrote most of the poems on which her reputation now rests. Within just five months she wrote “Daddy,” “Lady Lazarus,” “Poppies in July,” and “Ariel.”

In December of that year, she returned to London with their children and rented a flat on Fitzroy Road. This was only a few streets from the couple’s London residence.

As fate would have it, the winter of 1962–63 was one of the coldest in a century. The water pipes froze, the children (now two years old and nine months) were often sick, and the house had no telephone to contact the outside world.

Between too many sleeping pills, crying babies, and an unrelenting flu, Plath grew haunted by the thoughts and imagery that would inhabit her final works. Even as her depression worsened, she managed to put the final touches on Ariel.

Published after her death, Ariel was praised by the New York Times for its “relentless honesty,” “sophistication of the use of rhyme,” and “bitter force.” Poetry magazine cited it as having “a pervasive impatience, a positive urgency to the poems.”

The Bitter End

By January of 1963, Plath had made several attempts to end her life. Meeting with her physician, John Horder, she reported that her current bout of depression had endured for six or seven months and was only worsening.

She was constantly agitated. She constantly entertained suicidal thoughts. She felt she could no longer cope with day-to-day life. She described her level of despair as “owl’s talons clenching my heart.”

Horder prescribed an anti-depressant just a few days before her suicide. Knowing she was alone with two small children, he visited her daily. He strenuously advised that she allow him to admit her to a psychiatric hospital. When Plath refused, he arranged for a live-in nurse to keep watch over her.

On the morning of February 11, 1963, the nurse arrived at 9:00 but couldn’t get inside the flat. Eventually gaining access with the help of a man named Charles Langridge, the two found Plath dead; her head in the oven.

She had sealed the rooms between her and her sleeping children with tape, towels, and cloth. Upon visiting the scene, Horder said, “No one who saw the care with which the kitchen was prepared could have interpreted her action as anything but an irrational compulsion.”

Works and Growing Interest

Plath’s only novel, The Bell Jar, was published in January 1963 under the pen name Victoria Lucas. But it was met with critical apathy.

After publication, Plath began working on another literary work titled Double Exposure, which she never completed. According to Ted Hughes, Plath left behind a typescript of “some sixty, seventy pages,” perhaps constituting the first two chapters of a novel.

In 1981, eighteen years after her death, The Collected Poems (which includes many previously unpublished poems) was published. It received the 1982 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, making Plath the first to receive the honor posthumously.

In 1996, a children’s book she’d written in 1959 called The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit, was published. In 2000 The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath (covering the years 1950 to 1962) was published. And in 2009, Plath’s 1962 radio play, Three Women was staged for the first time.

In 2017, a collection of Plath’s letters (written between 1940 and 1956) was published. And a second volume (including a number written to psychiatrist Ruth Beuscher) appeared the following year. In 2019 the story, Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom, written in 1952, was finally published.

The So-Called “Sylvia Plath Effect”

In 2001, psychologist James C. Kaufman coined the term “Sylvia Plath Effect” in promoting the theory that poets are more susceptible to mental illness than other creative writers. Named for Plath, Kaufman’s studies demonstrate that female poets are more likely to experience mental illness than any other category of writer.

An independent study was performed by the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Kentucky Medical Center. They found that female writers were found more likely to suffer panic attacks, mood disorders, drug abuse, general anxiety, and eating disorders.

The rates of multiple mental disorders were also higher among these writers. Although it has not yet been explored in depth, abuse during childhood (physical or sexual) also appears to be a contributing factor to psychological issues in adulthood.

References

Britannica, “Sylvia Plath,” Sylvia Plath | Biography, Poems, Books, Death, & Facts | Britannica

“’Ocean 1212-W’ by Sylvia Plath,” https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/ocean-1212-w-by-sylvia-plath

ScienceChristianMonitor.com., “‘Red Comet’ is the biography Sylvia Plath has always deserved,” https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2020/1103/Red-Comet-is-the-biography-Sylvia-Plath-has-always-deserved

TheAtlantic.com., “The Haunting Last Letters of Sylvia Plath,” https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/sylvia-plath-final-letters/576400/

American Psychological Association, “The ‘Sylvia Plath’ effect,” Considering Creativity–The ‘Sylvia Path’ effect

PoetryFoundation.org., “Sylvia Plath,” Sylvia Plath | Poetry Foundation

McGrath.nd.edu., “Biography: Sylvia Plath,” https://mcgrath.nd.edu/assets/316752/biography_sylvia_plath.pdf