Civilizations throughout history have approached succession from numerous fronts, from religiously ordained kings to democracy and trials by physical prowess. These decisions arise from cultural, religious, and social beliefs, and what one civilization may view as just, another may not. In the case of the Ottomans, the means of succession occupied a middle ground: accepted by necessity, disdained by some morally.

The Ottoman Empire was one of the longest-lasting in history, spanning more than six hundred years (all the way until the 1920s!). Regions ranging from Europe to Western Asia and North Africa saw the influence of the Ottomans, and for rival Islamic states, the empire’s pressure remained constant and undeniable.

Though Islamic influence grew over time to become a significant influencer in the rules of succession, its different form in early decision-making prompted successions that many deemed morally dubious.

Osman I, responsible for founding the empire, grew the small principality by taking advantage of a weakening Byzantine Empire. Through skilled military tactics, the Ottomans gradually expanded by absorbing their neighboring states.

However, one historic moment truly cemented the Ottomans as a new power: when Mehmed II captured Constantinople in 1453. This singular strike ended the Byzantine Empire and established Constantinople as the capital of the Ottoman Empire, from which it exercised its dominance going forward.

However, around this same time and proceeding onward through the “Golden Age,” the Ottomans faced a significant challenge. Succession of the seat of power was no simple matter, and each new leader came with high risk, not just for the country as a whole, but for coalition families.

The Rules of Ottoman Succession

In the early Ottoman political culture, the eldest son was not guaranteed to inherit the leadership position. In fact, his age or qualifications had very little to do with his eventual rise. Instead, every son was a legitimate candidate.

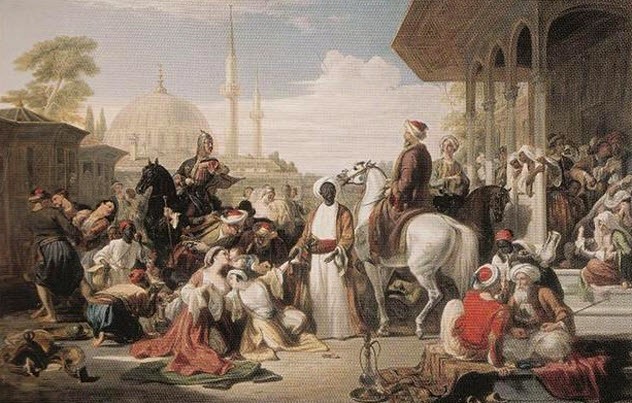

Typically, a sultan would send his sons to sanjaks, or small provincial governorships, where they would hold political positions. There, they could gain experience and build networks among supporters. When the sultan passed, the question of succession then became, “Who competes the best?”

That competition often came in the form of military aggression. Among equal contenders, each raced for the rank of sultan, and if that meant murdering a brother, then so be it.

Given that sultans typically fathered numerous children, repeated murders were often expected upon each shift in power. Killing a brother was most common due to their position as the primary potential heirs, but deaths also appeared among other family members as necessary to secure the position of sultan.

At this point, fragmentation remained a greater concern than murder. If only the eldest son stood to inherit the throne, expanding his governorship of a sanjak into its own competing state became simpler. Thus, by giving sons equal claims, the race for leadership turned inward rather than outward. This helped to prevent civil wars between newly risen groups and the central Ottoman leadership, which was an outcome that the Ottoman culture viewed as worse.

Socially and politically, the Ottomans accepted that civil war had a greater impact on the everyday man. Economic consequences, military forces among commoners, and local upsets typically led to more death and suffering compared to a few princes and related individuals dying. Thus, the practice continued, less because it was supported and more because it was the preferred alternative.

The Fratricide Law

Fratricide (the killing of a brother) continued as the standard practice for more than a century after the start of the Ottoman Empire. However, Mehmed II changed its reception. Mehmed, dubbed “The Conqueror,” rebuilt and centralized the empire by claiming Constantinople. With its power now localized, the succession problem became even more challenging; rivals could now become the source of complete imperial collapse.

In an effort to stabilize the expectations around succession, Mehmed formalized the existing practice of politically motivated murder in the Kanunname-i Âl-i Osman. The clause of note is commonly translated as: “Fratricide, for nizām-i ‘ālem (the common benefit of the people), is acceptable for any of my descendants who ascends the throne by God’s decree. The majority of the ‘ulemā (Muslim scholars) permits the fratricide,” though other related translations exist.

Thus, Mehmed II codified what was already a common practice using public good as the argument. Jurists could lend legitimacy to such declarations, but the concept remained state law, not Quranic mandate. This concept of the public good would persist for the entirety of the Ottoman Empire, albeit in gradually evolving forms.

The Major Succession Murders

In large part, the 14th-century Ottoman Interregnum prompted Mehmed’s push toward a standardized understanding of the law of fratricide. In 1402, Sultan Bayezid I participated in military engagements against Tamerlane (Timur) in the Battle of Ankara. Defeated, Bayezid was captured, and in his absence, the throne sat empty. From 1402 to 1413, the Interregnum (literally “between reigns) saw Bayezid I’s sons fight ardently for the throne.

The resulting civil war fractured the empire into competing power blocs. Each prince controlled an important region of the empire, bringing military and political might to bear in their attempts to seize power. During this time, the average citizen struggled to survive, prompting the Turkish name “period of famine” to describe the decade.

İsa was the first to fall, in 1406, marking four years of struggle before the stalemate progressed to its next stage. Seizing on the opportunity, Musa struck against Süleyman, whose initial resistance was overcome, leading to his death in 1411.

With only two brothers left, the region had undergone significant shifts. Having learned from Süleyman’s experience, Mehmed I crossed into Europe to confront Musa directly. Upon Musa’s death, Mehmed rose to a sultancy ravaged by the strain of prolonged regime change.

By then, foreign powers had gained greater control within Ottoman politics, and such large-scale political violence destabilized the social and economic order. This was the driver behind Mehmed II’s formalization of the concept of fratricidal law.

However, Mehmed’s “solution” came with gaps and, in some cases, unexpected implementations. In the 16th century, Selim I came into conflict with his father, Bayezid II, although the latter was still alive. His brother Ahmed was the favorite to succeed, and lacking the desire to rule further, Bayezid named Ahmed as his intended heir.

This upset Selim, who rose up, and though he lost his initial confrontations, he did succeed in dethroning his father. Following his rise to power, Selim killed Ahmed and Korkut, his other brother, to prevent further strife.

However, Selim went further. Unwilling to bear any threat to his throne, Selim proceeded to kill his nephews as well, extending down the family line to reduce the chances of a future rival.

This use of the law of fratricide demonstrated that the concept was not as contained as Mehmed’s original formalization. Increasingly, cultural expectations shifted to push back against the growing risk of political murder.

Later in the 16th century, interpretations mutated again. Suleiman’s son, Mustafa, arose as a serious contender to his rule. While participating in a military campaign against the Persians, Mustafa was executed, much to the shock and horror of the many common folk who favored their prince for his talents.

The exact situation surrounding his death is unclear, with some sources stating that Suleiman’s wife or court figures worked behind the scenes. However, modern historians treat these claims cautiously.

Succession in the Ottoman Empire was getting messier, and something needed to be done about it. So, at the end of the 16th and into the 17th centuries, Ottoman princes took a different approach, residing in confinement within the palace: the kafes. This controlled suite of rooms rarely contacted the outside world, preventing princes from building networks and coalitions that would later support their destabilizing rises to power.

The gradual introduction of the kafes attempted to solve another problem as well: resilience. When fratricide reduced a dynasty down to a single prince, risks such as illness threatened to shatter the sultancy. A single accident may lead to the death of the only heir, and the resulting confusion was noted as even more problematic than the civil wars the law of fratricide was meant to prevent.

Thanks to the kafes, the transition of power gradually evolved to accept the oldest surviving male dynast, which was usually the first son or oldest uncle. However, this streamlined process did not come without challenges of its own. Because the princes now lacked the practice with political leadership that they had formerly gained through sanjaks, their new powers as sultan often came as an unwieldy surprise.

Additionally, the personal effects of such isolation frequently impacted their functioning. Anxiety and paranoia were common, and most had little concept of social engagements.

While not all sultans suffered from mental health considerations, the prevalence of such challenges was frequent enough that an entirely new dynamic formed around it. Power began to shift into those surrounding the sultan, who found him easy to control. This commonly included the sultan’s mother as well as senior palace officials, viziers, and even cliques within the court.

In this sense, many historians make the comparison of the Ottoman Empire to England’s Wars of the Roses. While kingship passed through hereditary rights, political acceptance remained paramount. Thus, when a weak or incapacitated king (e.g., Henry VI) destabilized the monarchy, multiple plausible claims arose from powerful noble houses, each with private armies. This coalition warfare used claimants as figureheads, executing their own wills by strongarming potential claimants.

Like the Ottoman Empire, England’s approach also recognized that killing potential heirs was a possible outcome, though it was handled discreetly: deaths on the battlefield, “disappearances,” and the like. This difference is both cultural and functional, given the differing approaches to military might, political organization, and more.

However, the primary difference between the two nations comes down to justification. In England, most murders were retrospectively legally dismissed as punishment for treason. In the Ottoman Empire, the law of fratricide preemptively justified such behaviors.

Although kafes helped to decrease fratricide and the murders surrounding a person’s rise to sultan, these issues did not entirely disappear for some time. In the 17th century, the Kadızadelis arose in increasing numbers in Constantinople. This revivalist Sunni movement restored attention to Islamic values, and with this new focus, the succession strategy had to pivot.

Kadızadelis expanded religion to the forefront of the population’s mind once again, easing into society amid fiscal strain and political confusion. Short reigns and frequent sultan depositions allowed for the influence of the Kadızadelis to grow as a symptom of the succession crisis, not as a contributor to it.

With the Kadızadelis exerting religious pressure in society and increasing public support, sultan successors now needed to consider their Islamic legitimacy. Even though fratricide was legal, rulers faced increasing pressure to appear morally sound, religiously intact, and standing in defense of Sunni orthodoxy.

As a result, dynastic violence became a harder sell. As religious moralism swelled in influence, acts that could be framed as sinful, illegitimate, or problematic became more costly to a potential successor.

The shift toward a bloodless succession progressed, and the focus moved to deposition politics. Coups, interventions from the court, and similar tactics resulted in frequent flipping of sultan powers.

The public good, long considered an important standard in succession, battled with the difference between two opposing possibilities: the morality of more fratricide with the benefit of fewer depositions (the law of fratricide approach) or greater instability through frequent sultan upsets but less fratricide (the more moral option, according to Islamic beliefs).

In the end, the gradual move toward seniority-based succession won out over murder. This system existed, in varying forms, until the fall of the empire. Like many types of succession around the world, its development and adaptation arose from a combination of cultural, political, social, and religious pressures, and as with any system, its advantages and disadvantages play a part in defining the empire in which it was practiced.